E.Asia should heed strategic lessons of history

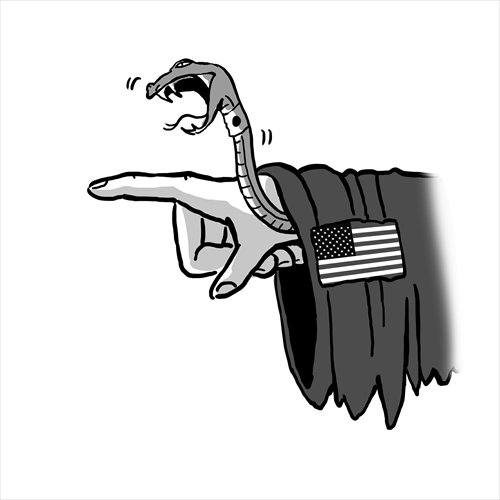

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The Japanese cabinet approved on July 1 a resolution to reinterpret the pacifist constitution and lift the ban on the right to collective self-defense. This represents the most overt revisionist maneuver in the security architecture of Northeast Asia since the end of the Cold War.

A recent poll shows that only 34.5 percent of Japanese citizens support this decision and 55.4 percent are opposed to removing the restriction. A 15-year-old middle-school student wrote to the Asahi Shimbun declaring that he firmly objected to Japan's exercise of the right to collective self-defense because he was unwilling to be conscripted and sent to the battlefield to kill civilians.

When then US president Richard Nixon was mulling how to open China's doors in 1969, he was at the same time seeking to give Japan a greater role in Asian affairs. Ever since then, a constant conundrum perplexing US strategic planners has been that Washington needs to make Tokyo do more - but not too much.

Nixon once conveyed to his secretary of state Henry Kissinger that Japan was a gray area that would seek to ramp up the military buildup to reequip itself, would probably seek security assurance from other powers and even forge an alliance with the Soviet Union, given a détente between China and the US.

At the same time, then Chinese chairman Mao Zedong and premier Zhou Enlai were also confronting a dilemma. They thought that the US would vigorously support Japan and make it the new master of Asia after withdrawing its troops from Vietnam. What was more dreadful was that Tokyo had been suspected of attempting to annex Taiwan since there were several pro-Japanese forces in the Chiang Kai-shek administration.

Chinese and US leaders ultimately achieved a tacit strategic understanding.

Since the US-Japan alliance could help constrain Tokyo's militarist impulses and prevent Japan and the Soviet Union from getting intimate, Beijing stopped asking Washington to annul its alliance with Tokyo, in light of Nixon's pledges that the US would never allow Japan to endorse Taiwan's independence.

This has constituted the foundation for the relative stability of the trilateral relationship among the US, Japan and China.

Nevertheless, it seems now that Washington, Beijing and Tokyo are seeking to abandon this foundation but have yet to find a functioning alternative. Asia and the world at large are mired in the shadow brought about by the strategic uncertainty in their trilateral ties.

The term "mutation" is pertinent to describe Japan's national strategic culture. Since the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), Japan has swiftly turned from an extremely closed pre-modern state to a Western-style civilized nation.

In 1905, Japan defeated Russian troops in Shenyang. Then the country embarked on the fascist path overnight in the 1920s when young military officers assassinated elected authorities.

A decade later, it waged aggression against China and more than 35 million Chinese people were killed in catastrophic warfare.

Japan's attack on the US bases in the Pacific in 1941 might be the most deadly strategic decision it has ever made. There were more than 3,000 American casualties in the attack on Pearl Harbor. After WWII, Tokyo had a pacifist constitution imposed on it under US pressure. Without enormous military expenditure, Japan rapidly became a world power in the 1980s.

Why did China and Japan fail to reach reconciliation like France and Germany?

The US expected Berlin and Paris to join hands to deal with the Soviet Union while it counted on Tokyo to hedge against Beijing. Now China is being viewed as a security threat, the same with Russia, North Korea and Iran, by Washington and Tokyo, which has become an open secret in their strategic military planning.

The resolution of the Abe administration to exercise the right of collective self-defense is an initial signal of the further deterioration of the Northeast Asian security situation.

All major regional stakeholders will adopt changes to their strategic plans in response to Tokyo's military ambitions.

US Secretary of State John Kerry has admitted that the US war on Iraq was a serious mistake.

But he may not realize that the US is committing a graver mistake and Washington has underestimated the consequence of Tokyo's actions to fundamentally change its national security strategies.

It will be perilous for the world to bear the risks of the trilateral relations among China, the US and Japan falling into strategic drift.

The author is a research fellow with the Charhar Institute and an adjunct fellow with the Center for International and Strategic Studies, Peking University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn