Genetic sequencing of human remains dating back 45,000 years has revealed a previously unknown migration into Europe and showed intermixing with Neanderthals in that period was more common than previously thought.

The research is based on the analysis of several ancient human remains - including a whole tooth and bone fragments - found in a cave in Bulgaria in 2020. Genetic sequencing found the remains came from individuals who were more closely linked to present-day populations in East Asia and the Americas than populations in Europe.

"This indicates that they belonged to a modern human migration into Europe that was not previously known from the genetic record," the research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, said.

It also "provides evidence that there was at least some continuity between the earliest modern humans in Europe and later people in Eurasia," the study added.

The findings "shifted our previous understanding of early human migrations into Europe," said Mateja Hajdinjak, an associate researcher at Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who helped lead the research.

"It showed how even the earliest history of modern Europeans in Europe may have been tumultuous and involved population replacements," she told AFP.

One possibility raised by the findings is "a dispersal of human groups that then get replaced [by other groups] later on in West Eurasia, but continue living and contribute ancestry to the people in East Eurasia," she added.

The remains were discovered in 2020 in the Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria and were hailed at the time as evidence that humans lived alongside Neanderthals in Europe significantly earlier than once thought. Genetic analysis also revealed that modern humans in Europe at that time mixed more with Neanderthals than was previously assumed.

All the "Bacho Kiro cave individuals have Neanderthal ancestors five-seven generations before they lived, suggesting that the admixture [mixing] between these first humans in Europe and Neanderthals was common," said Hajdinjak.

Previous evidence for early human-Neanderthal mixing in Europe came from a single individual called the Oase 1, dating back 40,000 years and found in Romania. "Until now, we could not exclude it being a chance find," Hajdinjak said. "Our study suggests... [it] must have been common."

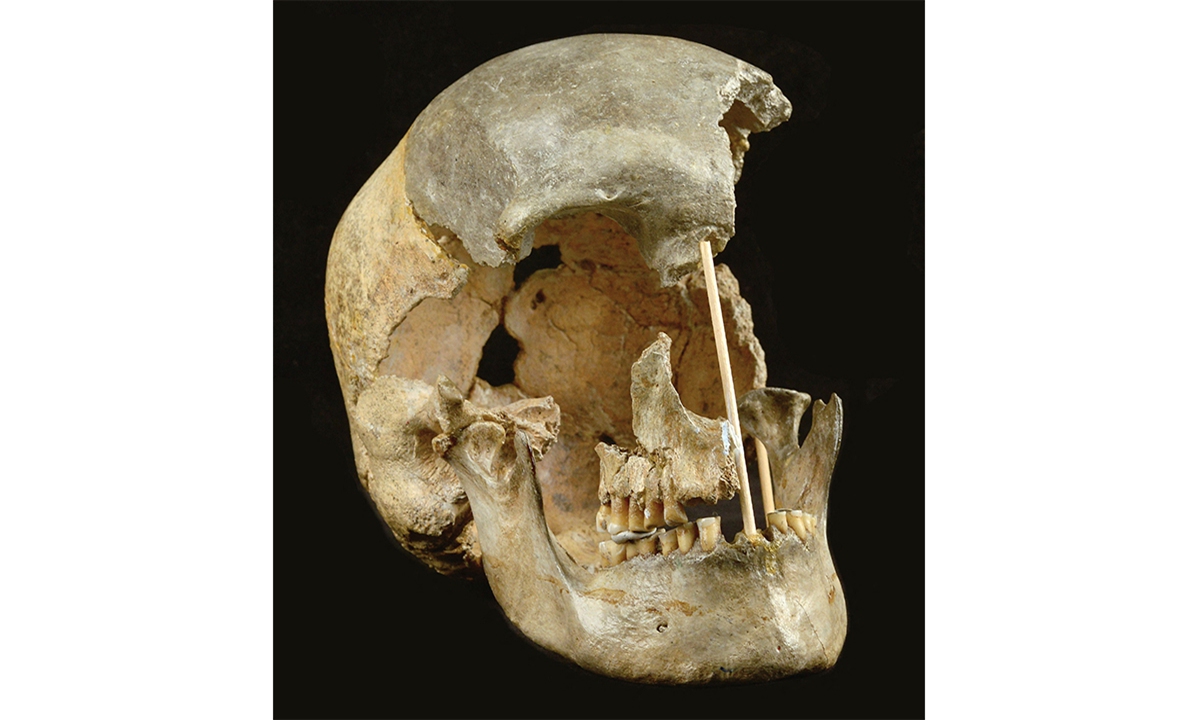

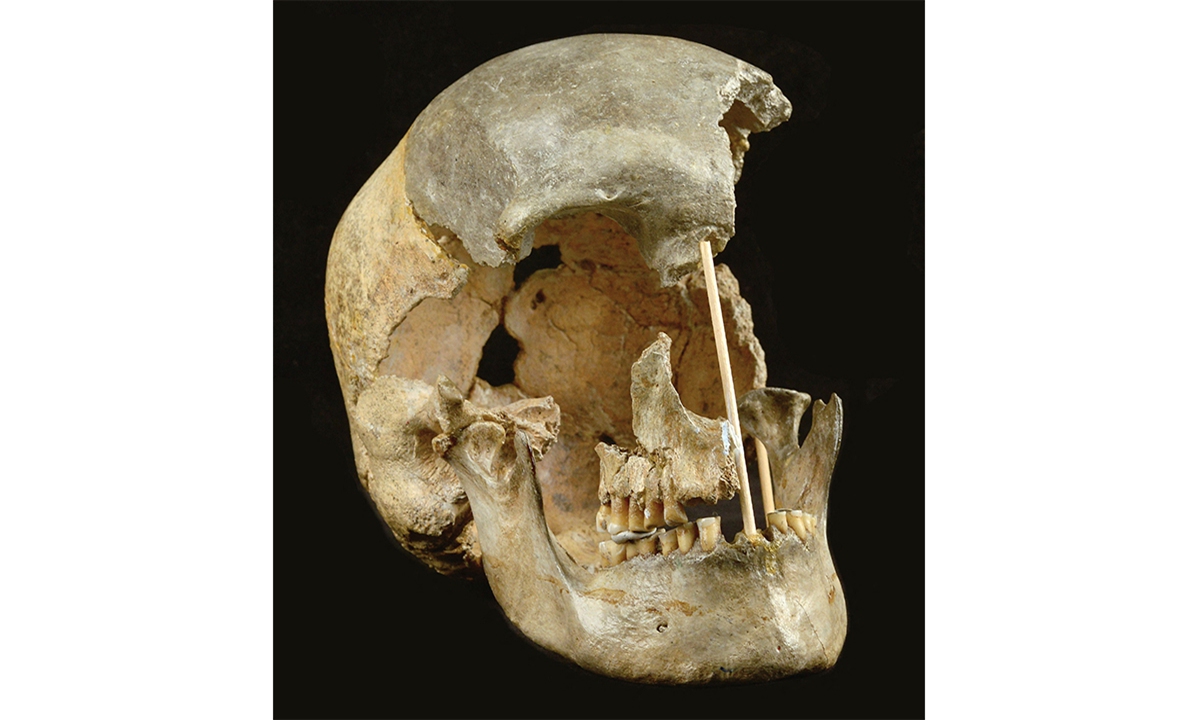

The findings were accompanied by separate research published Wednesday in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution involving genome sequencing of samples from a skull found in the Czech Republic. The skull was found in the Zlaty kun area in 1950, but its age has been the subject of debate.

The skull of a modern human female individual from Zlaty kun on April 7. Genetic sequencing of human remains dating back 45,000 years has revealed a previously unknown migration into Europe and showed intermixing with Neanderthals in that period was more common than previously thought. Photo: VCG

The research is based on the analysis of several ancient human remains - including a whole tooth and bone fragments - found in a cave in Bulgaria in 2020. Genetic sequencing found the remains came from individuals who were more closely linked to present-day populations in East Asia and the Americas than populations in Europe.

"This indicates that they belonged to a modern human migration into Europe that was not previously known from the genetic record," the research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, said.

It also "provides evidence that there was at least some continuity between the earliest modern humans in Europe and later people in Eurasia," the study added.

The findings "shifted our previous understanding of early human migrations into Europe," said Mateja Hajdinjak, an associate researcher at Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who helped lead the research.

"It showed how even the earliest history of modern Europeans in Europe may have been tumultuous and involved population replacements," she told AFP.

One possibility raised by the findings is "a dispersal of human groups that then get replaced [by other groups] later on in West Eurasia, but continue living and contribute ancestry to the people in East Eurasia," she added.

The remains were discovered in 2020 in the Bacho Kiro cave in Bulgaria and were hailed at the time as evidence that humans lived alongside Neanderthals in Europe significantly earlier than once thought. Genetic analysis also revealed that modern humans in Europe at that time mixed more with Neanderthals than was previously assumed.

All the "Bacho Kiro cave individuals have Neanderthal ancestors five-seven generations before they lived, suggesting that the admixture [mixing] between these first humans in Europe and Neanderthals was common," said Hajdinjak.

Previous evidence for early human-Neanderthal mixing in Europe came from a single individual called the Oase 1, dating back 40,000 years and found in Romania. "Until now, we could not exclude it being a chance find," Hajdinjak said. "Our study suggests... [it] must have been common."

The findings were accompanied by separate research published Wednesday in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution involving genome sequencing of samples from a skull found in the Czech Republic. The skull was found in the Zlaty kun area in 1950, but its age has been the subject of debate.