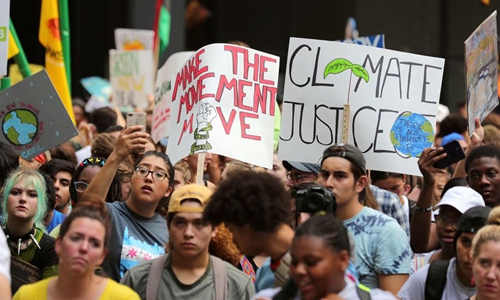

People participate in a strike to call attention to climate change in Chicago, the United States, on Sept. 20, 2019. (Xinhua/Wang Ping)

An atmospheric research station in Hawaii recorded its highest concentrations of carbon dioxide since accurate measurements began 63 years ago, a government agency said Monday, adding that the coronavirus pandemic had barely impacted rising levels of the greenhouse gas.The Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory's measurements for May 2021 averaged 419 parts per million (ppm), up from 417 ppm in May 2020, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said.

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego was also involved in the research.

"We are adding roughly 40 billion metric tons of CO2 pollution to the atmosphere per year," said Pieter Tans, a senior scientist with NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory.

"That is a mountain of carbon that we dig up out of the Earth, burn, and release into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide - year after year. If we want to avoid catastrophic climate change, the highest priority must be to reduce CO2 pollution to zero at the earliest possible date."

Carbon dioxide is the most abundant human-created greenhouse gas, and persists in the atmosphere and oceans for thousands of years after it is emitted.

It is generated by burning carbon-based fossil fuels used in transportation and power generation, construction, deforestation and other practices.

Greenhouse gases trap heat that would otherwise be lost to space in the atmosphere, thus contributing to planetary warming.

The May 2020 to May 2021 increase of 1.8 ppm was slightly less than previous years. However over the first five months of 2021, the average increase was 2.3 ppm, close to the annual rises seen 2010-19.

Although emissions dropped by 17 percent at the peak of shutdowns in 2020, that reduction was not large enough to stand out from seasonal variations caused by the way plants and soil respond to temperature, humidity and soil moisture.

"These natural variations are large, and so far the 'missing' emissions from fossil fuel burning have not stood out," NOAA said in an explanatory statement.