IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Australia reluctant to tackle climate crisis, blames it on developing world and China

Dust storm in Northern Wheatbelt, Western Australia Photo: VCG

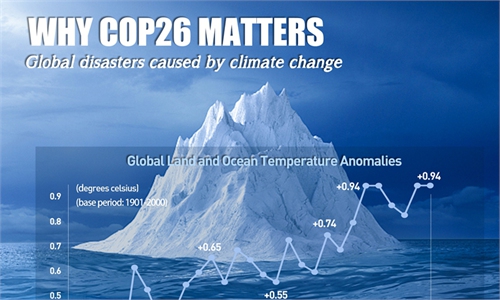

With the COP26 Summit ongoing in Glasgow, Australia has announced its long-awaited commitment to achieving a target of net zero emissions by 2050, amid mounting public pressure domestically and internationally, but that does not seem to be sufficiently convincing.As a notable emitter per capita, Australia is widely seen as a laggard in dealing with global warming. Australia has also long been much-maligned for refusing to set detailed targets for carbon neutrality, as one of the world's largest exporters of coal and liquefied natural gas.

Experts have pointed out that Australia's climate change performance is against their net zero goal, especially Australia's current reliance on coal. Experts have called on Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison to stop passing the buck and slamming China whose emissions per person are only around half of Australia's, and to better seek potential collaboration with China.

Unconvincing goal

Morrison announced a much-delayed climate plan only days before the COP26 summit, saying it would achieve net zero carbon emissions goal by 2050 through the continuing 2030 target of reducing emissions by 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels.

This announcement took months of political wrangling, BBC reported, but nothing new compared to the target set under former Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2016.

Australia, the leading global coal and fossil fuels exporter drew large criticism for a far modest pledge than other rich nations' ambitions, with nothing more updated that the goal announced at the Paris climate conference in 2015.

As one of the strongest emissions per head of population, it has long dragged its heels on climate action, though having seen direct influence over its own land such as extended bushfires, marine heatwaves, rising sea levels in Australia, and more frequent floods and drought.

Its pledge was accused of being the weakest at COP26 among the G20's developed countries, while others including the UK and the EU accelerated aims in cutting greenhouse gas emissions by moving toward a 50 percent reduction from 2005 levels.

Chris Bowen, Australia's shadow climate change minister, described the government's announcement as a "scam" with no new policy detail.

Climate activists hold placards during a protest against Australia's energy policy outside the Australian Embassy in Berlin on January 10, 2020. Photo: AFP

Public anger overseas and domestic

Worries and criticisms have long been spiking on Australian government's inaction on climate change. The media has reported on a batch of Torres Strait Islanders living in Australia's north coast who filed a lawsuit against the government, on the day the carbon emissions target was announced, for leaving the residents under the threat of floods and soil salinization as a result of global warming.

Australia has already experienced 1.4C — much higher than the global average of 1.1C — of warming that could bring about more intense and frequent fire weather events and other extreme weather fronts. And this will continue to increase, with serious impacts if action is not taken to reduce carbon emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2021.

"This report shows Scott Morrison's 2030 targets are a death sentence for Australia," Australia Greens leader Adam Bandt said.

Bandt called Morrison to double or triple the country's 2030 targets, saying that "anything less than 75 percent emissions cuts by 2030 means giving up on the 1.5 degree goal in the Paris Agreement."

Published data by researchers at Monash University shows that Australians are almost three times more worried about climate change than COVID-19, with many showing signs of PTSD from past or future climate-related, catastrophic events.

On August 10, a group of protesters sprayed the message "climate duty of care" on the concrete outside the Australian Parliament House and on a fence outside The Lodge before getting arrested.

"Australians are very concerned about the impact of climate change on Australia. Surveys show around 80 percent of Australians are very worried. We are already seeing the impact of extreme weather and we know this is just the beginning," Rhonda Garad, a senior lecturer and research fellow at Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, told the Global Times on Tuesday.

"Australia must do much better. We need to cut our emissions by 80 percent by 2030 to prevent global warming above 1.5," said Garad. "Morrison must follow the advice of scientists and enact strong climate action."

Australia's Prime Minister Scott Morrison presents his national statement at the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow on November 1. Photo: VCG

Passing the buck

Matthew Agarwala, an environmental economist at the University of Cambridge, revealed that Australians emit 3.37 times more CO2 per capita than the average global citizen, a number that jumps to 4.15 when including more potent greenhouse gasses such as methane.

Partly as a result of its government's inaction, Australia has been ranked at the bottom for climate action out of 193 countries in a UN report in July on evaluating efforts toward sustainable global development goals.

But Morrison has seemly never given up in seeking excuses.

As leading scientists call on the world to avert an impending climate catastrophe, Morrison responded by saying: "There is not a direct correlation between the action that Australia takes and the temperature in Australia," the Guardian reported.

"It's like a badly-behaved student in the class of the Paris Agreement, having neither credibility nor a good reputation among its 'classmates'," commented Chai Qimin, director of Strategy and Planning Department at the National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation.

Barriers to Australia's emission reduction mainly come from the country's polluting-intensive pillar industries including steel, iron, and coal mining, Chai analyzed. "Reducing CO2 emissions hurts the interests of Australian domestic giants in these industries," he told the Global Times.

Facing resistance from these interest groups, Australian administrations from the former Kevin Rudd's to current Scott Morrison's, have made little difference in reducing emissions, observers said.

The National Party of Australia, a part of Australia's ruling Liberal-National Coalition, actually represent farmers, grazers, and miners, said Chen Hong, a professor and director of the Australian Studies Centre of East China Normal University. "That leads to the very conservative attitude of the Morrison government [toward climate action]," he noted.

Also, inside the Australian government there are climate skeptics who don't believe that humans cause global warming, Chen told the Global Times. He mentioned former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, a climate skeptic who is also infamous for interference in China's internal affairs on the Taiwan question. "That's anti-intellectual," Chen said.

Worse still, the Australian government has frequently pointed fingers at China on emission reduction issues, turning a blind eye to the fact that China's emissions per person (around 8.12 tons) are far lower than that of Australia (15.2 tons), observers have found.

In his brazen defense, Morrison deflected blame onto developing countries, but it keeps absent in financing support to worldwide actions in climate change, as it has stopped contributions to the UN's Green Climate Fund and continues to fund the fossil fuel industry.

In a speech delivered in August, Morrison said that climate change must be solved "in developing nations such as China." "If we do not solve the climate change in developing countries, we, the world, will fail," he said, which sparked wide anger in the international community.

"This new narrative of blame is dark, and cruel," said an article published on Australia-based website Renew Economy in August. "It's another grim effort for leaders to shed themselves of any responsibility."

China's Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035 has in fact set a binding target of slashing carbon intensity by 18 percent from 2020 to 2025, and applauded by many countries for its clear stage goal.

The Morrison administration has been playing the climate change card to attack China, said Chen. "By weaponizing the climate topic, it tries to push China toward unrealistic and irrational targets," he told the Global Times.

Change and Cooperation

To get out of a domestic climate dilemma and win back trust and reputation, experts have pointed out that Australia should make up its mind in reducing its dependence on energy-intensive, raw material industries.

"Apart from giving promises to the international community, it must get down to make and implement [industrial transforming] related policies," Chai noted.

Enhancing international cooperation and making joint efforts in tackling climate change has become a global consensus. China and Australia, two major economies in the world, have huge room for collaboration in this regard, climate scholars of the two countries told the Global Times.

China and Australia can set common agendas, such as joining hands to help Pacific Island countries against climate challenges, suggested Chen.

Australia is pushing ahead technologies like the CCUS (carbon capture, use, and storage), Chai exampled. "It can cooperate with China in joint development and deployment of emission-reducing technologies," he said. "That will be a good thing for both."

"Australia and China are global citizens and both can drastically cut emissions," said Garad. "Collaborating is far better for protecting the planet."

Dust storm in Northern Wheatbelt, Western Australia Photo: VCG

With the COP26 Summit ongoing in Glasgow, Australia has announced its long-awaited commitment to achieving a target of net zero emissions by 2050, amid mounting public pressure domestically and internationally, but that does not seem to be sufficiently convincing.As a notable emitter per capita, Australia is widely seen as a laggard in dealing with global warming. Australia has also long been much-maligned for refusing to set detailed targets for carbon neutrality, as one of the world's largest exporters of coal and liquefied natural gas.

Experts have pointed out that Australia's climate change performance is against their net zero goal, especially Australia's current reliance on coal. Experts have called on Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison to stop passing the buck and slamming China whose emissions per person are only around half of Australia's, and to better seek potential collaboration with China.

Unconvincing goal

Morrison announced a much-delayed climate plan only days before the COP26 summit, saying it would achieve net zero carbon emissions goal by 2050 through the continuing 2030 target of reducing emissions by 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels.

This announcement took months of political wrangling, BBC reported, but nothing new compared to the target set under former Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2016.

Australia, the leading global coal and fossil fuels exporter drew large criticism for a far modest pledge than other rich nations' ambitions, with nothing more updated that the goal announced at the Paris climate conference in 2015.

As one of the strongest emissions per head of population, it has long dragged its heels on climate action, though having seen direct influence over its own land such as extended bushfires, marine heatwaves, rising sea levels in Australia, and more frequent floods and drought.

Its pledge was accused of being the weakest at COP26 among the G20's developed countries, while others including the UK and the EU accelerated aims in cutting greenhouse gas emissions by moving toward a 50 percent reduction from 2005 levels.

Chris Bowen, Australia's shadow climate change minister, described the government's announcement as a "scam" with no new policy detail.

Climate activists hold placards during a protest against Australia's energy policy outside the Australian Embassy in Berlin on January 10, 2020. Photo: AFP

Public anger overseas and domestic

Worries and criticisms have long been spiking on Australian government's inaction on climate change. The media has reported on a batch of Torres Strait Islanders living in Australia's north coast who filed a lawsuit against the government, on the day the carbon emissions target was announced, for leaving the residents under the threat of floods and soil salinization as a result of global warming.

Australia has already experienced 1.4C — much higher than the global average of 1.1C — of warming that could bring about more intense and frequent fire weather events and other extreme weather fronts. And this will continue to increase, with serious impacts if action is not taken to reduce carbon emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2021.

"This report shows Scott Morrison's 2030 targets are a death sentence for Australia," Australia Greens leader Adam Bandt said.

Bandt called Morrison to double or triple the country's 2030 targets, saying that "anything less than 75 percent emissions cuts by 2030 means giving up on the 1.5 degree goal in the Paris Agreement."

Published data by researchers at Monash University shows that Australians are almost three times more worried about climate change than COVID-19, with many showing signs of PTSD from past or future climate-related, catastrophic events.

On August 10, a group of protesters sprayed the message "climate duty of care" on the concrete outside the Australian Parliament House and on a fence outside The Lodge before getting arrested.

"Australians are very concerned about the impact of climate change on Australia. Surveys show around 80 percent of Australians are very worried. We are already seeing the impact of extreme weather and we know this is just the beginning," Rhonda Garad, a senior lecturer and research fellow at Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, told the Global Times on Tuesday.

"Australia must do much better. We need to cut our emissions by 80 percent by 2030 to prevent global warming above 1.5," said Garad. "Morrison must follow the advice of scientists and enact strong climate action."

Australia's Prime Minister Scott Morrison presents his national statement at the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow on November 1. Photo: VCG

Passing the buck

Matthew Agarwala, an environmental economist at the University of Cambridge, revealed that Australians emit 3.37 times more CO2 per capita than the average global citizen, a number that jumps to 4.15 when including more potent greenhouse gasses such as methane.

Partly as a result of its government's inaction, Australia has been ranked at the bottom for climate action out of 193 countries in a UN report in July on evaluating efforts toward sustainable global development goals.

But Morrison has seemly never given up in seeking excuses.

As leading scientists call on the world to avert an impending climate catastrophe, Morrison responded by saying: "There is not a direct correlation between the action that Australia takes and the temperature in Australia," the Guardian reported.

"It's like a badly-behaved student in the class of the Paris Agreement, having neither credibility nor a good reputation among its 'classmates'," commented Chai Qimin, director of Strategy and Planning Department at the National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation.

Barriers to Australia's emission reduction mainly come from the country's polluting-intensive pillar industries including steel, iron, and coal mining, Chai analyzed. "Reducing CO2 emissions hurts the interests of Australian domestic giants in these industries," he told the Global Times.

Facing resistance from these interest groups, Australian administrations from the former Kevin Rudd's to current Scott Morrison's, have made little difference in reducing emissions, observers said.

The National Party of Australia, a part of Australia's ruling Liberal-National Coalition, actually represent farmers, grazers, and miners, said Chen Hong, a professor and director of the Australian Studies Centre of East China Normal University. "That leads to the very conservative attitude of the Morrison government [toward climate action]," he noted.

Also, inside the Australian government there are climate skeptics who don't believe that humans cause global warming, Chen told the Global Times. He mentioned former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, a climate skeptic who is also infamous for interference in China's internal affairs on the Taiwan question. "That's anti-intellectual," Chen said.

Worse still, the Australian government has frequently pointed fingers at China on emission reduction issues, turning a blind eye to the fact that China's emissions per person (around 8.12 tons) are far lower than that of Australia (15.2 tons), observers have found.

In his brazen defense, Morrison deflected blame onto developing countries, but it keeps absent in financing support to worldwide actions in climate change, as it has stopped contributions to the UN's Green Climate Fund and continues to fund the fossil fuel industry.

In a speech delivered in August, Morrison said that climate change must be solved "in developing nations such as China." "If we do not solve the climate change in developing countries, we, the world, will fail," he said, which sparked wide anger in the international community.

"This new narrative of blame is dark, and cruel," said an article published on Australia-based website Renew Economy in August. "It's another grim effort for leaders to shed themselves of any responsibility."

China's Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035 has in fact set a binding target of slashing carbon intensity by 18 percent from 2020 to 2025, and applauded by many countries for its clear stage goal.

The Morrison administration has been playing the climate change card to attack China, said Chen. "By weaponizing the climate topic, it tries to push China toward unrealistic and irrational targets," he told the Global Times.

Change and Cooperation

To get out of a domestic climate dilemma and win back trust and reputation, experts have pointed out that Australia should make up its mind in reducing its dependence on energy-intensive, raw material industries.

"Apart from giving promises to the international community, it must get down to make and implement [industrial transforming] related policies," Chai noted.

Enhancing international cooperation and making joint efforts in tackling climate change has become a global consensus. China and Australia, two major economies in the world, have huge room for collaboration in this regard, climate scholars of the two countries told the Global Times.

China and Australia can set common agendas, such as joining hands to help Pacific Island countries against climate challenges, suggested Chen.

Australia is pushing ahead technologies like the CCUS (carbon capture, use, and storage), Chai exampled. "It can cooperate with China in joint development and deployment of emission-reducing technologies," he said. "That will be a good thing for both."

"Australia and China are global citizens and both can drastically cut emissions," said Garad. "Collaborating is far better for protecting the planet."