IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

New China-US pact key to solving global crisis, charts way forward for developing nations: Singaporean experts

Joint climate resilience

Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

Chinese President Xi Jinping said that climate change can well become a new highlight for China-US cooperation during a virtual meeting with his US counterpart Joe Biden on November 16. Xi reiterated during the meeting that all countries need to uphold the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, and strike a balance between addressing climate change and protecting livelihoods. The world is widely expecting cooperation on climate issues as a breakthrough in bilateral relations after the two countries released the China-US Joint Glasgow Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s at the COP26 in Glasgow on November 10. The Global Times reporter Hu Yuwei (GT) exclusively interviewed Singaporean political scientist Kishore Mahbubani (Mahbubani) and his research assistant Bertrand Seah (Seah), who co-wrote the commentary "Climate Justice: The Real Story" with Mahbubani. Mahbubani predicted the specific directions of US-China cooperation on climate issues and called on developed countries to maintain common but differentiated responsibilities.

Singaporean political scientist Kishore Mahbubani Photo: AFP

I. Chances and breakthroughs on climate change cooperation

GT: Given the existing diplomatic tensions between the two countries on such issues as trade, technology, and human rights, questions remain about whether China and the US can return to a cooperative momentum and confidence on the climate crisis similar to 2015. In the climate field, where might the US and China make the first breakthrough?

Mahbubani & Seah: Thankfully, climate change doesn't present any clear red lines in the broader geopolitical contest between the US and China. The challenge has always been to find a common agreement on climate cooperation in a much more constrained geopolitical environment. Notably, the return of Xie Zhenhua and John Kerry in 2021 was an attempt to revive the cooperative dynamic of 2015. As a result, even though 2021 has seen some barbed rhetoric from both, the surprise announcement of a joint declaration on climate between the US and China is a small breakthrough. This agreement will play a crucial step in preventing the worst outcome - that the two countries decouple in their climate diplomacy and scupper any further progress on international climate action.

The coming days will determine if further progress can result from this, firstly in the concluding days of COP26, and then at a virtual summit between Xi and Biden on November 16. There are many areas where much deeper cooperation on climate change between the US and China could occur. The US could work with China to develop and build up its green infrastructure, which remains sorely inadequate, it could develop closer trade links with China on renewable energy technology, or it could work with China's Belt and Road Initiative to build climate resilience around Asia and Africa.

II. Efforts prominent, but challenges remain

GT: In your opinion, what are the most prominent achievements and challenges the world's countries face in working together to fight against climate change?

Mahbubani & Seah: The main achievement is the Paris Agreement itself, where every country agrees on the need to tackle climate change, and to keep the world to 1.5 C of warming. To get every single country to agree on the importance of fighting climate change is no small diplomatic feat. Indeed, it was truly remarkable that even though the US under the Trump Administration walked away from the Paris Agreement, the world remained firmly committed to it. This meant that when Joe Biden was elected as president, the door was open for the US to return.

There have been significant developments in the past year. Perhaps the most notable is China's announcement in September 2020 that it would reach net zero by 2060. The historian Adam Tooze said that with this announcement, "China permanently changed the global fight against climate change." Japan and South Korea shortly followed this by announcing their own net zero targets in October 2020, as did India this COP26. Today about 90 percent of global emissions are covered by a net zero target. Nonetheless, the UN still estimates that the world is on track to warm by 2.7 C. This tells us that much more still needs to be done.

The main challenge has been geopolitics. It is clear that climate change is a global issue that demands global cooperation. Just like COVID-19, it should have been clear that the world needed to work together to come up with solutions for handling these global issues. Unfortunately, rather than press the pause button on its geopolitical contest with China, Trump decided to accelerate it instead. Sadly, the Biden Administration has not reversed it.

Xie Zhenhua (left), China's special envoy for climate change, speaks with John Kerry, US special presidential envoy for climate, during the COP26 on November 13, 2021. Photo: AFP

GT: China officially announced in late September that it would stop new overseas coal power projects. A study published in July by Boston University found that only about 13 percent of new coal-fired power plants in operation or planned outside China from 2013 to 2018 were financed by Chinese money. While according to independent researches, the private sector in the G7 and other advanced economies has long been the primary financer of coal projects worldwide. What is your comment on the Chinese government's pledge and what efforts should developed countries make to guide overseas investment toward "green assets"?

Mahbubani & Seah: A key part of the green transition is to ensure that finance is channeled away from fossil fuels and toward green assets. China's decision to stop financing coal power projects abroad is therefore a welcome move. Domestically, it has also made progress, cutting the share of coal in its energy consumption from 70 percent in 2009 to 57 percent in 2020. In advanced economies, the private sector, including the world's largest and most powerful banks, have recently signed on to Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, but many of its signatories remain among the world's largest backers of fossil fuels. The private sector needs to be doing much more.

The International Energy Agency estimates that to reach net zero, there can be no new investments in oil, coal, or gas projects, while total energy investment must rise from about $2 trillion today to $5 trillion in 2030. A major transition such as this will require the "invisible hand" of free markets to be guided by the "visible hand" of government planning. A recent article by University of North Carolina Professor Angel Hsu in Singapore's Straits Times gives a good account of how government planning can spur this shift, even amid an energy crisis. As she says, "A thorough reading of China's State Council's six orders issued on October 8 reveals that beyond the immediate coal production increase, the government cites the crisis as a reason to speed up its transition to a green economy to better weather spikes in energy demand, and achieve energy security. That effectively means accelerating away from coal." Tellingly, even major Western publications such as the Financial Times and the Economist are calling for more government planning to facilitate a green transition.

III. Role of balance between developed and developing countries

GT: You have argued in your commentary that climate change is not only caused by greenhouse gas emissions from emerging developing countries, but also the result of the "stock" of greenhouse gas emissions from developed Western countries since the Industrial Revolution. From two dimensions of stock and per capita emissions, China and India's carbon emissions are much lower than those of developed countries in Europe and the US. How do you comment on this pressure and even accusations levied by some Western countries against developing countries? How should China balance its own developing right and its global commitment on climate change?

Mahbubani & Seah: China and India have an important role in tackling climate change by virtue of sheer demographics. The two countries account for over a third of the world population. It is a truism that the actions of China and India will have a significant bearing on the climate, positive or not, especially as they are also two of the fastest growing major economies in the world. Thankfully, both have announced that they will hit net zero, China in 2060 and India in 2070. Indeed, the green transition presents a major economic opportunity for countries that can carry out this transformation effectively.

China has been at the forefront of developing the technologies and infrastructures that are needed for a green transition. Nonetheless, in the short- to medium-term they still have significant developmental needs, as do much of the rest of the world. Developing countries must still have the opportunity to improve the lives of their people. This is where the "stock" of greenhouse gas emissions matters.

Developed countries have played the biggest role in causing climate change, and to let the rest of the world develop they have to acknowledge this. This is why the climate scientist Ken Caldeira says that "the remaining carbon budget is a development budget."

The stance of Western countries against developing countries goes against the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, which they agreed to at the 1992 Rio Summit. Under this principle, developed Western nations accepted that they had their historical responsibility in causing climate change and they would take the lead in tackling it. They could have taken a big step towards this by fulfilling their pledge to providing $100 billion a year in climate finance to developing countries. Sadly, they have not done so. By trying to shift the onus for climate on developing countries and not doing more to help them, they have neglected the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities.

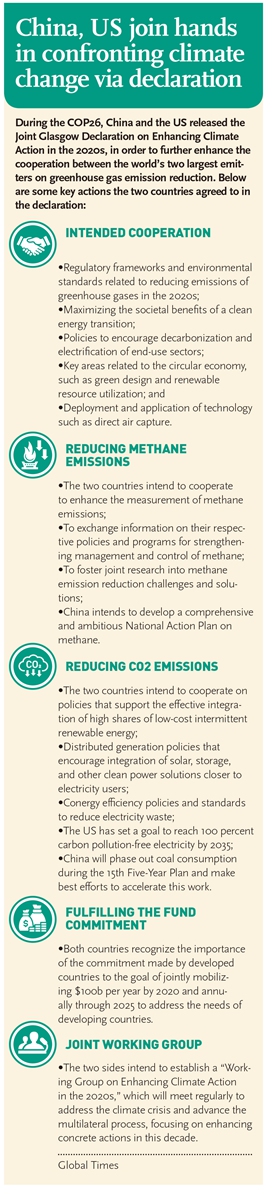

Graphic: Global Times