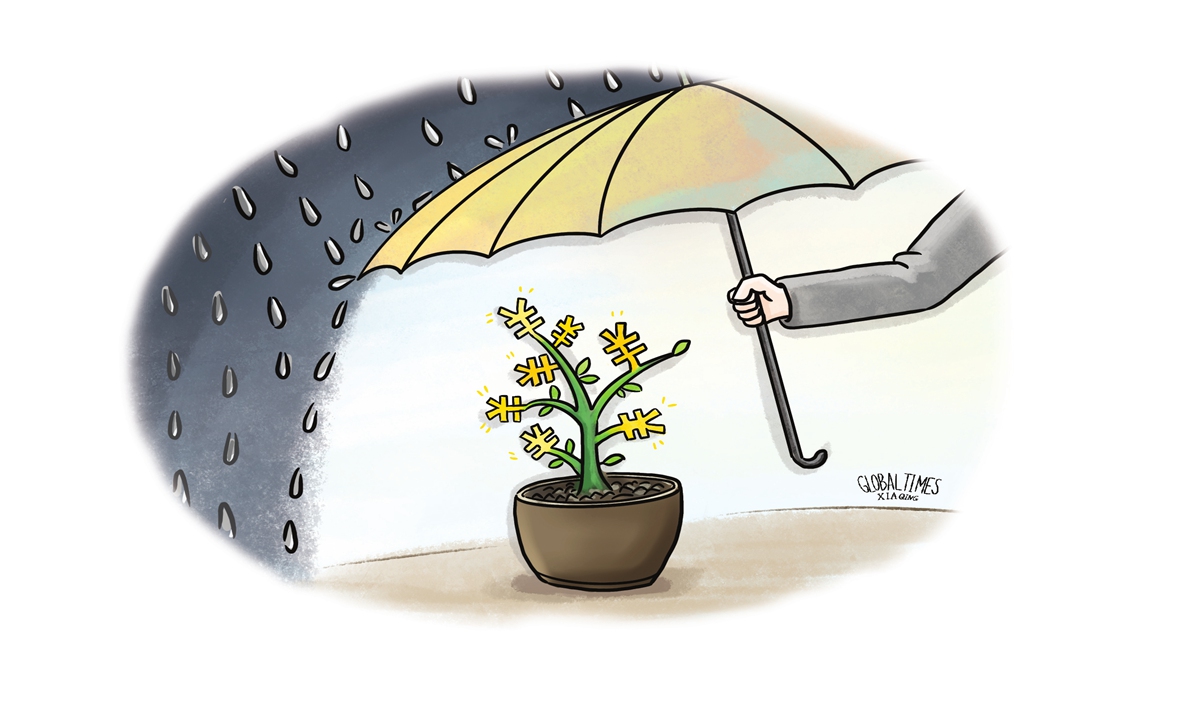

Illustration: Xia Qing/Global Times

China's economy grew by 3 percent in 2022, dragged down by strict anti-epidemic restrictions, as well as a retreating real estate sector. The "anemic" growth was immediately picked up by some Western organizations and news media to cast doubt on the country's future development.A recent Financial Times opinion piece, quoting "new research" by Citigroup analysts, drew an analogy between China's coming economic trajectory and Japan's "Lost Decade" of painful recession from 1991 to 2001, warning "if it is not careful, China may be on track for a new wave of Japanification." After the "Lost Decade," the article wrote, Japan could no longer "fool itself that all was well," adding Japan "once seemed capable of overtaking the US (in GDP)" - which contains an untold undertone that China can neither.

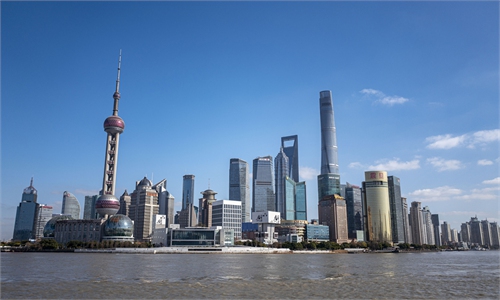

Ironically, the latest statistics point to a totally different roadmap for China's economy, which may prove some Westerners' concerns or rather expectations about China could be seriously flawed. The official purchasing managers' index for Chinese manufacturing hit 52.6 in February, the highest level since 2012, while the index for non-manufacturing sectors including construction and services surged to 56.3 - meaning economic activity in China has expanded rapidly for a second straight month after the country moved to shake off the impact of the epidemic. The data is deemed "exceptionally strong," confirming a sizzling rebound of the world's second-largest economy.

There is also positive news with regard to the housing sector. The sales of China's top 100 property developers reached 461.6 billion yuan ($67.4 billion) in February, up 14.9 percent on a yearly basis and 29.1 percent on a monthly basis, according to a report released by China Real Estate Information Corporation last week. The real estate sector slump in the past three years, induced by the epidemic, will give way to a significant growth in both housing sales and new housing investment in 2023, so the risk facing the sector is now significantly defused.

Chinese economists are expecting more institutional reforms and targeted pro-growth measures to fuel domestic consumption and infrastructure buildup, solidify financial sector, foster and propel scientific and technological innovations, and encourage new child-births - at the annual session of the National People's Congress, which opened in Beijing on Sunday.

By whatever metrics, China's economy is very likely to regain lost momentum and bounce back to annual 5-6 percent growth in the coming years. The country's current setting bears no similarity to Japan's predicament since 1991, with the most remarkable differences being China's asset prices are not subject to a bubble, and its inflation levels have been maintained at around 2 percent for many years, thanks to the central bank's effective and prudent monetary policy fine-tuning.

Like the 2008-2009 global financial crisis triggered by the US' sub-prime housing loans meltdown, Japan's "Lost Decade" was a period of severe economic distress caused by the asset price bubble's collapse in 1991, when Japan's stock market tanked, real estate market floundered, big banks failed, and companies folded. And, the 1985 Plaza Accord in New York exacerbated the Japanese asset bubbles. In early 1991, the Nikkei stock index lost 43 percent of its value just one year from its all-time highs. The term of "Lost Decade" originally referred to the 1990s, but the 2000s and the 2010s have been included by economists as the economic slump had largely continued in Japan. Now, some organizations predict Japan's GDP may lose out to Germany in 2023.

Citigroup analysts said China today looks "strikingly similar" to Japan in its post property bubble era. Will China's real estate sector fail just like Japan in early 1990s and the US in 2008 as the pundits anticipate? The answer is No.

There doesn't exist an asset bubble in China's housing and stock markets right now. Prior to the epidemic in 2020, housing prices could be deemed excessively elevated then, but China's central government took the initiative in 2021 to curb the debt levels of developers by controlling their bank borrowings.

The deleveraging campaign was successful in watering down the exuberance in property investments, and as a result, the overall housing prices edged down in most Chinese cities. The campaign even led to a slump in the real estate sector in 2022, but with the country's grand recovery from the pandemic, housing sales are rebounding and the sector is reviving, which is unlikely to cause a systemic financial risk to Chinese banks.

Also, China's stock market is not bubbly at all, with the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index closing at around 3,328 points on Friday, which is widely considered a very healthy level. With the country's rapid economic rebound, Chinese equities will trend higher in 2023, with some analysts estimating the Shanghai index to reach 3,500 or even higher.

And, the pundits compared Chinese and Japanese demographic evolutions, asserting China's population drop of 850,000 in 2022 is not auspicious, just like how Japan faced a shrinking population years ago. Yes, the demographic structural change is worth attention from policymakers, but there won't emerge a labor force drainage in the coming several years, though the country needs to immediately work out more preferential policies, say massive tax reliefs and fiscal give-outs, to inspire more child-births. Population decrease is truly a hidden risk, which could be mitigated if China takes prompt decision to address it.

The author is an editor with the Global Times. bizopinion@globaltimes.com.cn