ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Restoring ‘the old as old’ top criterion for refurbishing Palace Museum

Red walls, golden hands

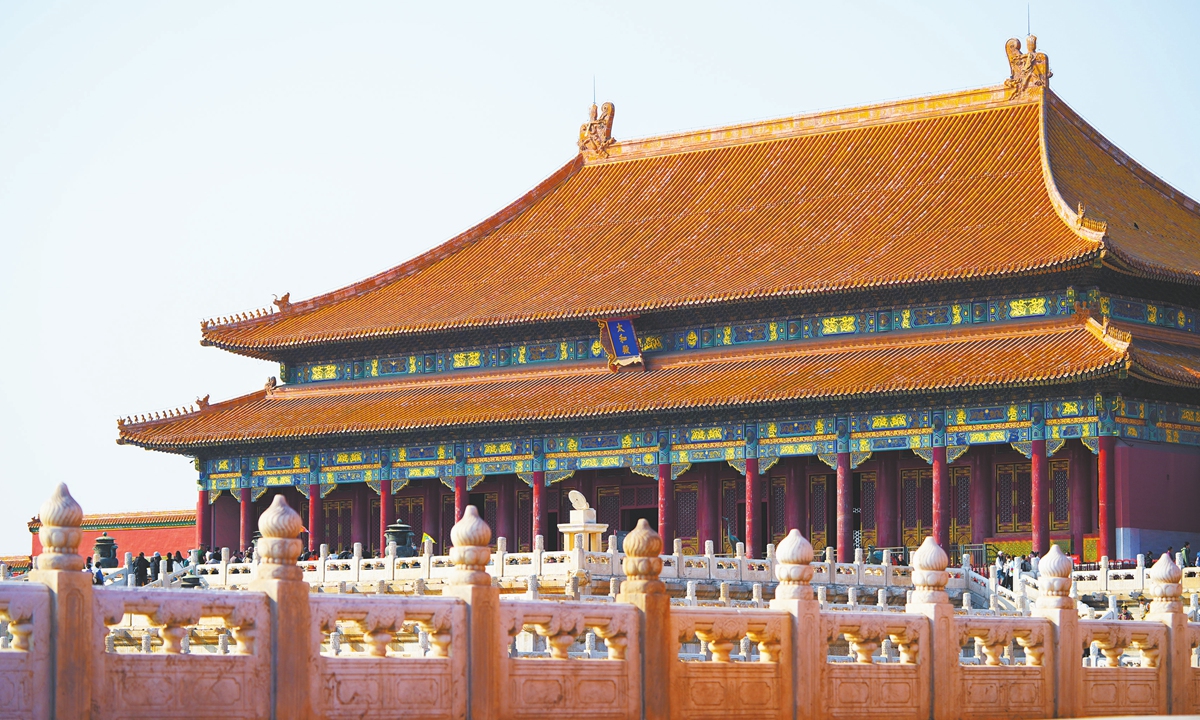

The Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian) of the Palace Museum in Beijing Photos on this page: VCG

The air hums with focused energy as 237 restoration specialists bend over fragments of history at the Beijing qualifier for the 2025 National Cultural Heritage Vocational Skills Competition. Overseeing it all, his eyes sharp with decades of discernment, is the referee Li Yongge.At 70, the third-generation inheritor of the 100-year-old Palace Museum's official ancient building techniques, Li surveils the participants with quiet satisfaction.

"Young people have truly filled the ranks of this profession," Li told the Global Times warmly.

It was a moment far removed from 1975. Then, a 19-year-old Li entered the crimson sanctum of the Palace Museum, an apprentice to second-generation master carpenter Zhao Chongmao.

Like many, Li initially saw it as merely a job to support his family.

Yet, the timbered majesty of the palace complex, the scent of aged wood, and traditional mortise-and-tenon joints infused themselves into his being.

What began as work became Li's life-long devotion, guarding and restoring this wooden architecture for about 50 years.

Li Yongge

Mastering the heartbeat of woodLi recalled that his early days were a blur of tasks: Fixing a partition screen today, replacing a table leg tomorrow.

Under his master Zhao's guidance, Li learned voraciously. He said he has developed a clever strategy. "If one master explained something clearly, and another asked 'Do you understand?' I'd say 'No,'" Li chuckled. "Hearing it explained from another angle would cement the knowledge."

Years flowed into decades, marked by countless repairs. When asked how many structures he'd restored, Li simply replied, "Uncountable."

But one project loomed largest: The Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian), the Palace Museum's grandest and highest-ranking structure, anchoring its central axis.

In 2006, this monumental hall, standing for over 300 years since the Kangxi period of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1912), underwent its first major restoration.

Li led the immense effort, his figure a near-constant presence within the vast green construction enclosures shielding the site.

"Three centuries had passed without repair," Li reflected, adding "The glazed tiles had faded, yet the historical resonance remained palpable. Protecting that history was paramount."

The challenges were immense, centering on two principles: Preservation and authentic replication of ancient methods.

When sagging roof tiles demanded an investigation, Li's team peeled back sections of the upper roof.

Their discovery was startling: The crucial waterproof layer beneath, known as "shanbei," from centuries ago was far more simplified.

For a structure of Taihe Dian's supreme status, experts insisted the restoration use the complex "lead-back" method - thin lead sheets layered with hemp, lime, and mud, involving seven or eight painstaking steps.

Li's team recreated the authentic Kangxi-era "shanbei," experimenting tirelessly to replicate the precise ratio of tung oil in the lime mixture. "shanbei" refers to an ancient Chinese architectural waterproofing technique.

Another critical task was restoring the exterior painted decoration.

Comparisons with historical photos revealed the exterior designs, repainted in the 1950s-60s, were inaccurate.

The interior, however, retained the pristine patterns of the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). To recreate the exterior authentically, Li employed "taoqi" - a method akin to tracing, devoid of artistic reinterpretation.

"We created patterns based largely on rubbings taken directly from the corresponding interior beams," Li explained.

This quest for authenticity bordered on the obsessive.

Li constantly emphasized mastering the perfect tension. It governed everything: The precise force applied, the exact timing, and the measurement of materials. It was the soul of craftsmanship, demanding relentless attention to the smallest of details.

Preserving aged facade

Li revealed that guiding his hand was the core tenet of Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics.

"Do not alter the original state of the cultural relic," Li said.

He distilled this into the "four originals": Original materials, original craftsmanship, original structure, and original form. Achieving this often felt like a quest into the unknown.

Consider the museum hall's flooring: The legendary "golden bricks." These were imperial treasures of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911), famed for their density, smoothness, and metallic ring when struck.

The finest clay came solely from a kiln village in Suzhou, East China's Jiangsu Province.

Ancient artisans subjected the bricks to a two-year odyssey: extracting soil, molding, firing, kiln extraction, grinding, and soaking.

Replacing damaged bricks meant sourcing replacements. While some original palace stock remained, new bricks were essential.

Li's team tracked down descendants of the Suzhou imperial kiln craftsmen, encouraging them to revive the ancient methods to meet the Palace Museum's exacting standards.

Yet, this fidelity has sparked debate.

What defines "restoring the old as old?" Does repair risk making the ancient complex appear too youthful?

"Experts interpret this differently," Li noted. "Restore it to look aged, or restore its original brilliance? Our principle remains unchanged: Preserve the relic's original state."

Before his master Zhao retired, he pressed a note into Li's hand, which can be translated as "guard against complacency with a single skill; resist the urge to skim the surface."

Li has carried these words through decades. Retired but indefatigable, Li journeys across China, sharing a lifetime's wisdom of traditional architecture.

His hope is profound: That ancient treasures are guarded with equal reverence, their essence faithfully passed on.

He sees great promise in the young restorers flooding the field, drawn to specialties like painting and ceramics.

"They embrace new tools," Li told the Global Times, but crucially, "their core philosophy remains steadfastly traditional."

Li stresses the importance of the "craftsman's spirit," which encompasses dedication to one's craft and a strong work ethic.

"If you do a job, love it … every trade can produce experts," he said.