GT Voice: Tariffs merely futile choice as fix for structural causes of US trade deficit

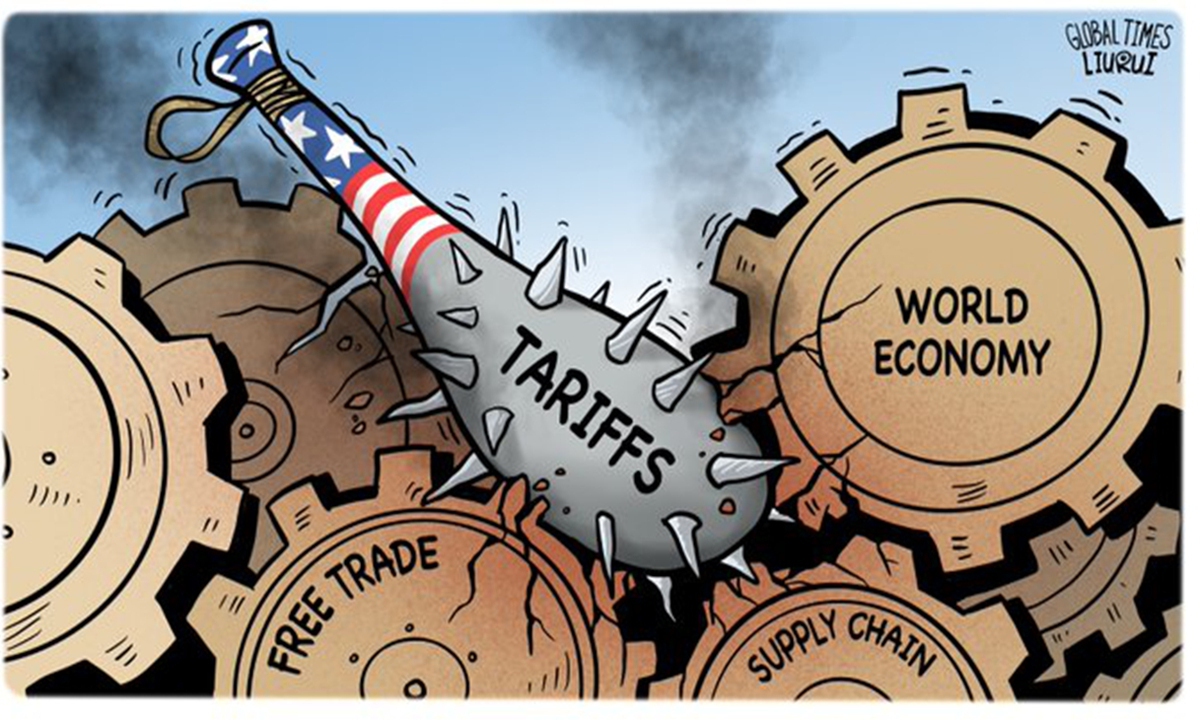

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

While the ripple effects of the sweeping tariffs that the US imposed on global trade continue to reverberate, it seems that Washington is already poised to wield a new round of tariff measures, further complicating the landscape of international commerce.US President Donald Trump on Thursday unveiled sweeping new import tariffs, including 100 percent duties on patented drugs and 25 percent levies on heavy-duty trucks, a 50 percent tariff on imported kitchen cabinets and bathroom vanities, as well as a 30 percent levy on upholstered furniture, which will go into effect on Wednesday, Reuters reported.

The development came just one day after the US Commerce Department said it had opened new Section 232 investigations into the import of personal protective equipment, medical items, robotics and industrial machinery, which a Bloomberg report said further expands the scope of industries potentially facing tariffs.

The introduction of a new round of tariffs and investigations not only further increases the uncertainty in the global trade environment but also reflects Washington's eagerness to reverse its economic situation through protectionism.

The three areas targeted - heavy trucks, pharmaceuticals and furniture - share a common characteristic: They are sectors where the US faces considerable trade deficits. While the move appears aimed at addressing these trade imbalances and revitalizing domestic manufacturing, a closer examination of the recent change in US trade deficits reveals that such tariffs are unlikely to achieve their intended goals and may, instead, inflict greater harm on the US economy.

It is true that the US trade deficit has fluctuated sharply this year. Specifically, the trade deficit narrowed 16.8 percent (month-on-month) to $85.5 billion in August, which seems to show that the tariff policies are working. But a careful analysis of the root causes of the narrowing deficit reveals that this change is more due to the passive shrinkage of imports, rather than a substantial enhancement of US export competitiveness, let alone a sign of sustained improvement in the economic fundamentals.

True improvement in the trade deficit should be built on the basis of export growth and economic vitality. Only when export competitiveness is strengthened can it truly reflect the recognition of US products in the global market, thereby driving the expansion of relevant domestic industries and laying a solid economic foundation for balanced trade. Yet, the current US approach relies on curbing imports through elevated tariffs, not on replacing them with competitive domestic alternatives. This approach of "narrowing the deficit by sacrificing imports" cannot address root causes of trade imbalances and risks plunging the US economy into a new predicament due to supply chain disruptions.

Enhancing export capability cannot be achieved by policies alone. It depends on multiple factors, including the strength of the US dollar and the overall competitiveness of the manufacturing sector. A strong dollar, for instance, would make American goods more expensive in international markets, undermining export growth even if domestic producers seek to expand abroad. Moreover, the revival of US manufacturing faces structural hurdles such as technological gaps, labor shortages and fragmented supply chains. None of these problems can be resolved overnight through tariff barriers. Without addressing these foundational challenges, simply restricting imports to drive industrial growth will not create a virtuous cycle of reduced imports and increased exports. Instead, it may disrupt the complementary balance of the US economy and reduce overall efficiency.

The revitalization of manufacturing depends on a supportive industrial ecosystem, sustained innovation, stable demand and sound policy guidance, not short-term trade protection. Tariffs may temporarily limit foreign competition, but they cannot create the genuine driving force needed for industrial advancement.

The frequent imposition of tariffs by the US will inevitably trigger a new round of frictions with its trading partners, which will further constrain the market space for US exporters.

The US trade deficit is the outcome of decades of globalized production, the structure of the American economy and consumption patterns. If Washington continues to indulge in unilateral protectionist measures, it will only further damage economic efficiency, and ultimately deviate from the original policy intentions, undermining the long-term competitiveness of the US in the global economy.