ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Mooncakes mirror China’s regional culinary diversity

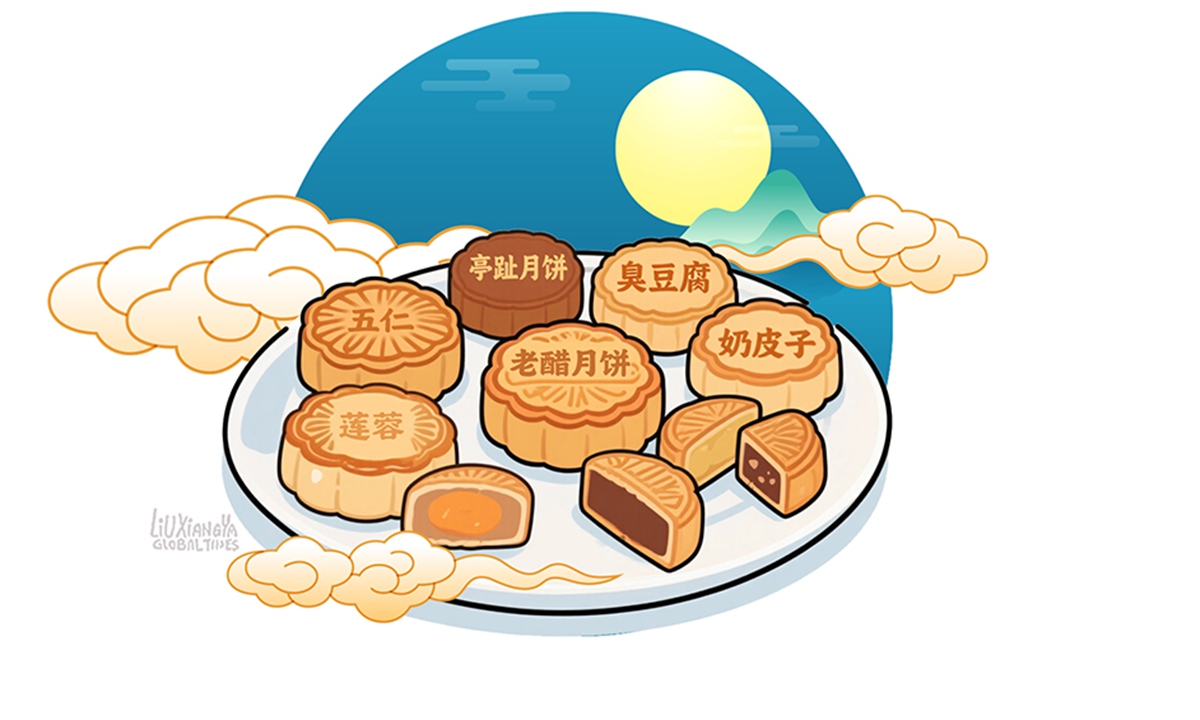

Illustration: Liu Xiangya/GT

Let's be honest, there is no other treat quite as essential to China's Mid-Autumn Festival as the mooncake. As the holiday draws near, this celebratory traditional pastry has already quietly begun dotting shelves in stores and supermarkets nationwide.

Besides the snack family's star member, "five-nut mooncake," the market has started to give way to a wave of bold new flavors. Be it fillings of "vinegar" or "stinky tofu," novel mooncake flavors may sound unusual, but they are actually sketching the landscape of China's regional cultures.

How unusual these emerging mooncakes may taste can be well-illustrated with examples. In Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, local workshops produce their popular sweet-and-sour "vinegar mooncakes," distributing them across the country. From Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, comes the "Tingzhi mooncake," a local classic treat filled with ham and spiced salt.

Other mooncakes push the boundaries of consumers' imagination even further. Street food favorites like "stinky tofu," grilled sausage, and even Luosifen, a rice noodle dish with a snail soup base, have been transformed into the pastry's fillings. Meanwhile, "milk skin," the rich layer from boiled milk, has also found its way into the pastry's competitive market.

The emergence of these flavors is no accident nor entirely about the pastry industry's promotional efforts. They are, in fact, the result of the region's local ingredients, cultural tastes and history.

The "vinegar mooncake" directly draws upon Shanxi Province's more than 3,000 years of vinegar-making heritage. Similarly, the "milk skin mooncake" is influenced by the nomadic dairy tradition of North China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, while a bite of the "stinky tofu mooncake" instantly conveys the love for salty and spicy flavors characteristic of Hunan Province's cuisine.

Put simply, the variety of flavors actually functions like an "edible tourist map," providing consumers with a direct taste of China's regional diversity. This tangible, sensory engagement goes beyond literal description or physical distance, leaving a deeper and more lasting impression than simply reading about history ever could.

On the contrary, thriving regional mooncakes can also inform people in a particular region about their cultural uniqueness. As the old saying goes, "You are what you eat." Food culture is not only about eating, but also about one's cultural identity and memory. In this sense, the rise of diverse mooncakes also reflects local confidence in their cultural roots.

For the Chinese, the Mid-Autumn Festival began as a folk custom for moon worship during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The mooncake's history has also evolved alongside this tradition. There was a time when ingredients were less diverse and cultural globalization had yet to reach local palates. Mooncakes filled with "five-nuts" and "date paste" were the mainstream for generations since such ingredients were easy to source from native grains and farmland.

But today, as modern China's resources and food industry have extensively developed, innovation in mooncake fillings has naturally flourished. Yet, the very Chinese ritual of sharing them with family and friends remains unchanged. Thus, embracing these novel mooncakes is not a detour from tradition, but a contemporary refreshing of it, ensuring its relevance in today's culture.

Thinking deeper, behind the small festive pastry lies the evolving life encounters and tastes of Chinese people across different areas. Also, the mooncake has stood witness to how Chinese tradition is not just passed down through old texts, but through the lives of ordinary folks.

"New mooncakes plus old tradition," this cultural fusion not only reflects people's creativity in celebrating tradition, but also reminds people that the existing market continues innovating.

This explains the reason why in recent years the food market, represented by the mooncake, has started cross-industry collaborations such as with museums and universities. Also, the cross-sector flow and consumers' open, curious mindset have made mooncakes no longer the exclusive domain of the food industry. Filled with locally sourced ham, mooncakes produced by a hospital in Southwest China's Guizhou Province have gone viral online. They are also now being sold at "several outlets" of an upscale supermarket in Beijing.

"It has become a buzzworthy attraction. Customers are drawn to them for photos. Having them is a true win-win since they provide a novel ritual for customers in Beijing and also help us differentiate ourselves from other supermarkets," Huang Wei, a salesperson at the store, told the Global Times.

Be it from the perspective of creators, consumers or the market, the little mooncake seems to have unlocked a living, participatory cultural arena that mirrors contemporary life. From its production to the moment it reaches a diner's plate, multiple forces were involved in the renewal and co-creation of the festival's meaning by redefining its classic snack.

While intriguing, regional mooncakes must avoid becoming marketing stunts. Their development should instead focus on a sincere exploration of local culture, backed by rigorous food safety standards. Also, as seasonal products, their production must be carefully calibrated to match actual demand, avoiding the pitfalls of overproduction and food waste that often accompany popularity.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. life@globaltimes.com.cn