Photo: VCG

A survey released by Bitkom, Germany's digital association, showed that about two-thirds of the German companies surveyed have no confidence in whether the US can continue to be a reliable semiconductor supplier, according to a report issued on the website of the association.The figure represents more than just anxiety among German businesses; it exposes the dilemmas and awkwardness faced by the EU in its semiconductor industry development.

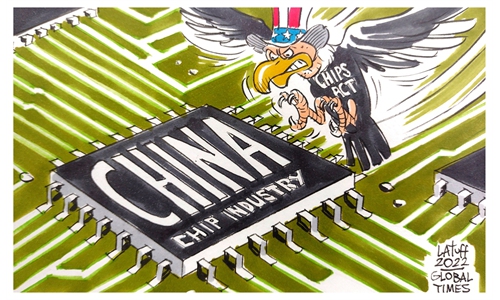

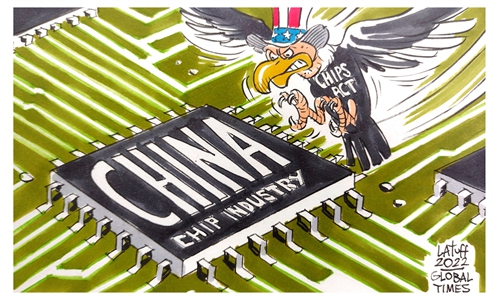

As the US has aggressively reshaped the global semiconductor landscape through the CHIPS and Science Act and its export control measures, the EU's Chips Act has struggled to gain meaningful traction. The gap between strategic ambition and actual implementation is the fundamental reason why the EU cannot provide its businesses with alternatives for chip supplies.

Looking back at the evolution of the global semiconductor industry, the shift in US policy is the root cause of the current turbulence in the global chip supply chain. What was once a highly globalized, efficiently specialized industry has become fragmented by geopolitical design. The US has excessively politicized the semiconductor sector, recklessly imposing export controls and forcing its allies to "take sides" in terms of technological restrictions to build a "small yard, high fence" tech alliance. One of the consequences is that countries around the world have all prioritized chip self-sufficiency, pushing the global chip supply chain from integrated collaboration into an era of fragmentation.

For the EU's semiconductor sector, this fragmentation carries particularly severe consequences. The EU announced the European Chips Act in February 2022, with the ambitious goal of producing 20 percent of the world's semiconductors by 2030. But that has proven to be easier said than done. For instance, Intel announced in July that it had abandoned its plan to construct a large-scale semiconductor facility in Germany, a major setback to Europe's chip ambitions.

That cancellation is just an isolated case. The fundamental challenge facing the EU's ambition of achieving semiconductor autonomy is the industrial fragmentation within the bloc, rather than funding or technology. From investment and research and development to innovation and production, EU member states struggle to unify their interests, industrial policies, and regulatory standards. This vulnerability allows the US to easily exploit such fragmentation, binding the EU to its own chip strategy and leaving the EU in a passive position in the semiconductor field.

To achieve chip autonomy, the most fundamental and arduous task for the EU is not to confront external forces, but to strengthen internal integration. This goes beyond just concentrating investment and resources; more importantly, it requires forging synergy in policymaking, standards unification, and market opening, breaking down barriers among member states, and building a unified, efficient, and competitive chip industry ecosystem. Only in this way can the EU secure a place in the restructuring of the global chip industry and avoid the risk of being marginalized.

International cooperation offers the EU another pathway beyond its predicament. On a global scale, China is undoubtedly a key partner that can form effective complementarity with the EU and jointly address challenges. China's rapid development in the chip industry is reflected not only in the expansion of its market scale but also in the significant improvement of its technological innovation capabilities.

Cooperation between China and the EU in the semiconductor field represents more than mere economic complementarity; it could serve as a stabilizing force in an increasingly fragmented global technology landscape. Such cooperation could accelerate innovation, optimize supply chains, and help build a more open, inclusive, and balanced order for the global chip industry.

The key to this cooperation lies in whether the EU can resist American influence and avoid aligning with its chip containment strategy against China. Should the EU choose to follow in the footsteps of the US and impose similar containment measures on China, it would inevitably become a casualty of the US-China chip rivalry, with its own technological sovereignty and economic interests hurt for America's geopolitical objectives.

As China and the US accelerate the development of their semiconductor ecosystems, the EU needs to promptly adapt its chip strategy by enhancing internal integration and expanding external cooperation; otherwise, it risks undermining its position in the global semiconductor race.