China achieving average annual growth of 5–6% before 2035 is attainable: Justin Yifu Lin

New quality productive forces to drive China’s economic development: economist

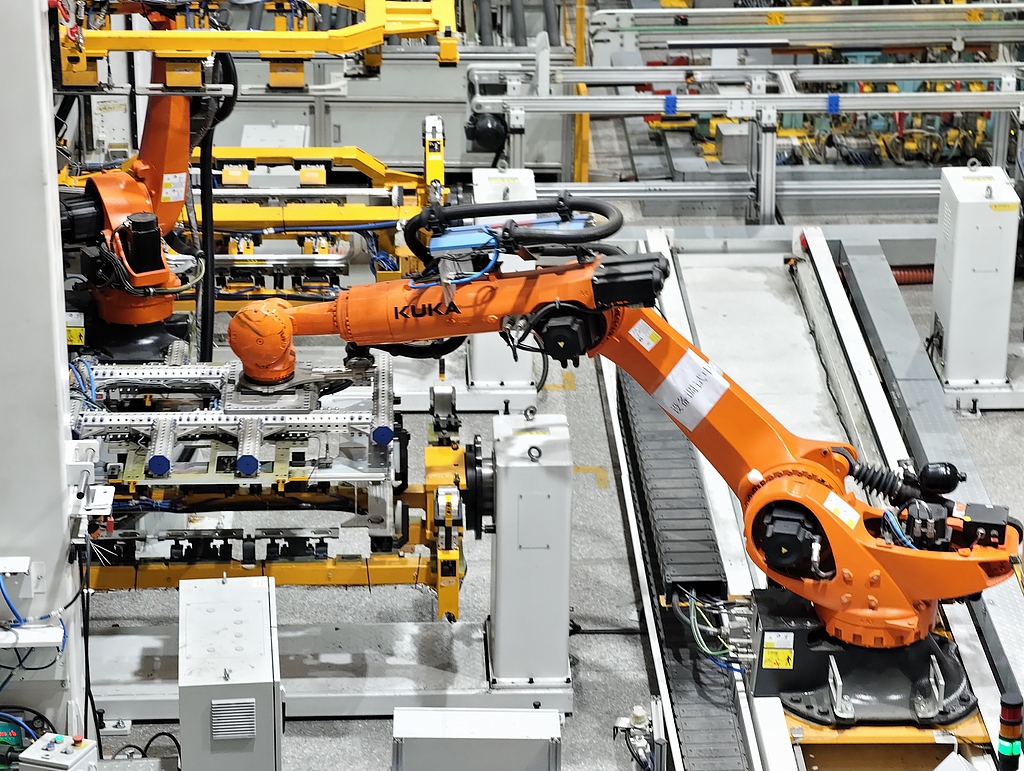

Robotic arms perform precision operations at an intelligent factory in Nanjing, East China's Jiangsu Province, on September 20, 2025. Photo: VCG

What drives China's sustained growth

Since the start of reform and opening-up, why has China's economy expanded so rapidly? To answer this question, we must first examine the essence of development.

Development ultimately manifests in rising income levels, and sustained income growth hinges on continuously improving productivity. This requires the emergence of new quality productive forces by constant innovation in existing industrial technologies and the rise of higher value-added industries which constitute the source of new quality productive forces and determine the pace of development. This applies equally to developing and developed economies.

However, there is a key difference between the two. Since the Industrial Revolution, developed countries have operated at the technological and industrial frontier. To continue innovating, they must invent new technologies and create new industries themselves - an endeavor that demands massive investment and carries extremely high risks. While success can yield extraordinary returns, most attempts end in failure. As a result, their per capita GDP growth has remained relatively modest since the Industrial Revolution.

Developed countries have no choice but to engage in invention because they already operate at the world's technological frontier; without inventing, there would be no new technologies or new industries. By contrast, developing countries can clearly see that the technologies they currently use are less advanced and their industries generate lower value added. Developing nations can pursue two paths for technological innovation and industrial upgrading: independent invention or leveraging the latecomer advantage by importing, digesting, and absorbing existing technologies as the basis for reinvention. Independent invention carries high costs and risks, whereas absorbing mature foreign technologies entails far lower costs and significantly reduced risks.

Based on this, developing countries that effectively leverage the latecomer advantage can innovate and upgrade more rapidly than developed nations. In theory, their overall growth can outpace advanced economies, though the specific magnitude cannot be precisely quantified and must be assessed through historical experience.

Justin Yifu Lin, dean of the Institute of New Structural Economics at Peking University, and former chief economist and senior vice president of the World Bank

What lies ahead for China's future devt

Today, some hold pessimistic views about China's development prospects, mainly due to population aging and China-US frictions. Internationally, narratives such as "China has peaked" have emerged. So, what does China's outlook truly look like? In my view, everything hinges on China's development potential. If we remain pragmatic and continue to emancipate the mind, rapid growth remains fully achievable.

How should China's development potential be assessed? As noted earlier, China's rapid growth has stemmed from leveraging the latecomer advantage. Some question whether, after more than four decades of fast development, that advantage still exists. In reality, whether the latecomer advantage remains does not depend on how long we have used it or how high our current level is, but on how large the gap remains between China and advanced economies. That gap is the true source of the latecomer advantage. Its essence lies in the distance separating developing countries from the frontier.

The latecomer advantage enables developing countries to grow faster, though the extent must be judged against historical experience. In 2019, China's per capita GDP in PPP terms was 22.6 percent of that of the US - comparable to Germany's gap with the US in 1946, Japan's in 1956, and South Korea's in 1985. All three economies delivered exceptional performance at similar stages. Germany's per capita GDP grew 8.6 percent annually from 1946 to 1962; Japan's rose 8.6 percent annually from 1956 to 1972; and South Korea registered 8.1 percent annual growth from 1985 to 2001. Based on these precedents, China's technology gap with the US suggests potential for 8 percent annual per capita GDP growth in the 16 years starting from 2019.

Moreover, China enjoys an advantage that Germany, Japan, and South Korea did not have at the time: the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Its hallmark is artificial intelligence and big data - technologies characterized by very short R&D cycles that require far less capital. DeepSeek, for example, was developed by only a few hundred people over three to four years, implying modest financial input. In 2024, China's per capita GDP stood at $13,445, far below the US level of $85,000, indicating a vast gap in capital strength. Yet the short R&D cycles and lower capital requirements of the Fourth Industrial Revolution make human capital the decisive factor. Human capital -particularly STEM education - forms the foundation of this revolution. China produces over 6 million university graduates annually in these fields, exceeding the total of the G7, giving the country a significant talent advantage.

China also benefits from a massive domestic market - the world's largest in PPP terms, which enables new technologies and products to achieve economies of scale quickly. In addition, China possesses the most comprehensive industrial supply chain globally.

Taken together, China has around 8 percent growth potential before 2035, a figure that is not an overestimate. Some may ask whether US technological restrictions undermine China's ability to leverage the latecomer advantage. In reality, the US is not the sole supplier of most of the technologies China needs; other advanced economies also possess them and are willing to trade. Thus, such chokepoints are extremely rare. With China's new national system for mobilizing resources toward major scientific and technological breakthroughs, we have ample reason to believe that these bottlenecks can generally be overcome, often within three to five years.

While China retains 8 percent growth potential before 2035, turning that potential into reality requires overcoming challenges such as population aging. Although aging does not reduce growth potential, its social impacts must be addressed by ensuring adequate care for the elderly. US restrictions are not fatal, but they require China to maintain sufficient resources for sustained technological breakthroughs. At the same time, China must pursue high-quality development and respond to global climate challenges.

Nevertheless, I believe that given China's 8 percent growth potential, achieving average annual growth of 5-6 percent before 2035 is realistic. Using the same analytical framework, China should retain around 6 percent growth potential between 2036 and 2049, enabling 3-4 percent annual growth. If achieved, China's per capita GDP could reach half that of the US by 2049.

Once China's per capita GDP reaches half of the US level, the goal of national rejuvenation will be achieved. At that point, China-US relations should also improve. Today, the US launches trade and tech wars because it still holds superiority in technology and defense. By 2049, however, when China reaches half of US per capita GDP, the more developed regions, such as Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and five eastern coastal provinces, could reach parity with the US. This implies comparable levels of labor productivity and industrial technology. China would then exceed the US in overall economic size while matching it technologically, leaving the US unable to impose technological blockades.

Second, China's economic size will be twice that of the US by then, and US high-tech firms cannot afford to lose the Chinese market. With China's market twice as large, losing access would shift these firms from high profit to low profit - or even unprofitable - operations. High-tech industries require sustained, substantial R&D investment, which in turn depends on strong profits. Competition in the sector is intense, making the Chinese market vital to the survival of US high-tech companies.

Currently, the US frequently resorts to trade conflicts because China's economic size is approaching its own and because the US still has advantages in high-tech sectors that allow it to impose restrictions. By 2049, however, the US will no longer be able to "choke" China technologically, and its economy will be smaller than China's. Trade between the two countries will benefit the US even more than China, giving Washington strong incentives to maintain stable relations. At that stage, the world's two largest economies will be fully capable of peaceful coexistence, forming an important cornerstone of global stability and development.

The author is dean of the Institute of New Structural Economics at Peking University, and former chief economist and senior vice president of the World Bank.