ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Major archaeological discoveries at Wuwangdun revive the Chu state ritual and musical civilization

The flute-like reed instruments discovered and restored by Chinese archaeologists from Wuwangdun tomb in Huainan, East China's Anhui Province Photo: Screenshot from website

A series of major archaeological discoveries at the Wuwangdun tomb in Huainan, East China's Anhui Province, is shedding new light on the ritual and musical civilization of the ancient state of Chu, offering rare insights into Chinese history from the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770BC-256BC) through the Qin Dynasty (221BC-206BC) and the Han Dynasty (206BC-AD220).

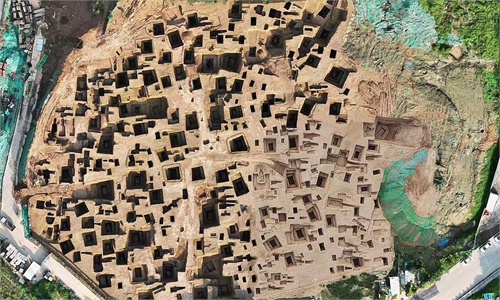

The Wuwangdun tomb is the only Chu royal mausoleum in China that has been scientifically excavated to date. Archaeological fieldwork concluded in December 2024. The Global Times learned from the Anhui Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, that after a year of conservation and restoration, researchers have confirmed a wealth of new findings, many of which are of significant academic significance.

Among more than 10,000 unearthed artifacts, musical instruments stand out for their sheer number and diversity. More than 50 instruments including se zithers and over 20 ancient flute-like reed instruments sheng and yu have been identified. Some of the se measure over two meters in length, making them the largest examples ever found in China. The concentration of wind and string instruments provides tangible evidence of the grand musical scenes described in Chu Ci, or the Songs of Chu, such as the line "the yu and se in frenzied assembly," and reflects a major transformation in musical forms during the Warring States period.

Zhang Wenjie, head of the first archaeological team of the Wuwangdun project, told the Global Times that the instruments were painstakingly reconstructed from numerous fragments, a process that took considerable time. According to inventory records from Tomb No.1, the instruments are certainly sheng and yu, though determining precisely which belongs to which category requires further academic research. "What is clear," Zhang said, "is that these are undoubtedly musical instruments of that system."

At present, five sheng and yu artifacts are stored in climate-controlled conservation laboratories. Although many of the pipes are broken and fragmented, the mouthpieces and wind chambers are relatively intact and can be smoothly assembled. The chambers feature 14, 16 or 20 holes for inserting pipes. One surviving pipe fragment, about 15 centimeters long, has two tone windows near the top and a finger hole at the bottom, while some pipes retain reed slots designed to hold rectangular metal reeds.

"The exact appearance of the sheng and yu, and how to distinguish between them, remains an academic puzzle," Zhang said. "Ancient texts generally state that the larger instrument was called yu, while the smaller was sheng."

Zhang noted that from the Spring and Autumn period through the Qin and Han dynasties, the yu was once regarded as the "leader" of musical instruments. In Zhou ritual music, performances typically began with unaccompanied singing, followed by sheng and yu, then the addition of zithers, bells and chimes, culminating in a full ensemble. The yu thus held a central place in ancient ritual music. From the Tang Dynasty onward, however, the instrument gradually fell out of use.

In addition, Tomb No.1 yielded a 2.1-meter-long se, hailed by archaeologists as the "king of zithers" discovered so far. The tomb also produced the largest tiger-seated bird-frame drum ever found, and the highest total number of musical instruments from a single burial.

The more than 50 se unearthed each have between 23 and 25 strings. Some archaeologists have even ventured the hypothesis that the "fifty strings" mentioned in a poem by Tang Dynasty poet Li Shangyin may refer to a 25-string se conceptually divided into two parts.

"The greatest value of restoring and studying these instruments lies in helping us reconstruct the ritual and musical civilization of that era," Zhang said, adding that further restoration and research will continue.

Beyond musical artifacts, the tomb has also yielded China's first known bamboo ruler from a Chu royal burial. Measuring about 69.4 centimeters in length, the ruler bears clear markings indicating that one foot in the late Warring States period measured approximately 23.1 centimeters. This suggests that standards of weights and measures were already converging before Qin unification.

Scientific analysis of residues found in bronze vessels such as tripods has also revealed plant remains including plums, gourd seeds, ginger and dates, as well as animal remains from cattle, pigs, fish, and ducks. The bones show signs of cooking, providing valuable material for studying Chu dietary practices and ritual food systems.

Experts say the systematic discoveries at the Wuwangdun tomb vividly illustrate the richness of Chu culture and the continuity of Chinese civilization, from institutional systems to everyday life. According to archaeologists, these findings will be unveiled to the public in an upcoming exhibition at the National Museum of China.