ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

‘Dougong Grandpa’ brings ancient architecture back into the public eye

Between wood and time

The dougong structure of a building at the Wenmiao Temple in North China's Shanxi Province Photo: VCG

In the early morning in Taiyuan, capital of North China's Shanxi Province, sunlight filters through centuries-old cypress trees in front of the Shengmu Hall (Holy Mother Hall) at the Jinci Temple, constructed in Tiansheng Period of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), casting mottled shadows across the corridors and the dougong brackets beneath the eaves.

Standing before the hall, Wang Yongxian holds up a selfie stick. He speaks neither fast nor loudly, his tone calm and measured, but what he talks about is not the scenery, rather the structural wisdom hidden within the beams and brackets overhead.

Such scenes are nothing new to him. The difference is that decades ago, he came for surveys, measurements, and restoration, but today he is here to "tell the story to more people."

Over just two-plus years, Wang has attracted more than 2 million followers on short-video platforms, with many of his videos surpassing one million views. Netizens have given the gray-haired scholar an affectionate nickname "Dougong Grandpa," according to China Media Group.

"Dougong is a key structural element in traditional Chinese architecture. It bears immense weight from above while supporting the far-reaching eaves," Wang told the Global Times.

"What I want is to be like a dougong myself - to serve as a bridge in between, passing China's outstanding traditional culture on to younger generations," he said. "To turn what once felt 'hard to understand' into something people can truly see and grasp."

Standing for a millennium

Dougong, one of the most iconic structural elements of ancient Chinese timber architecture, has traditionally been explained through technical drawings, terminology, and proportions. This professional language sets a high barrier to understanding and often creates distance between the subject and the general public.

At the Shanxi Institute of Ancient Architecture Conservation, Wang had spent 28 years working on the restoration of cultural relics. A few years after retiring, he first tried posting videos while explaining ancient architecture, just to see if this way of presenting would attract any viewers.

To his surprise, the response came quickly. The comment sections soon filled with questions and discussions from young viewers, and some even shared how they had been inspired to travel to Shanxi's historic sites.

"Breaking down complex structures and letting people look directly at abstract ideas is the key to connecting professionals with the public," Wang noted.

Under his explanations, dougong is no longer just a technical term in textbooks. He likens it to "building with LEGO": without a single nail, it can stand firm for a thousand years, an embodiment of the ancient wisdom of using timber to achieve strength through flexibility.

According to Wang, during earthquakes the structure disperses force like a spring, while in wind and rain it supports the eaves like an umbrella. Behind the structure lies a philosophy of reverence for nature and coexistence with it.

In his explanations, Wang favors everyday metaphors. He compares a single-tier dougong to a slice of pizza: Seemingly just curved pieces of wood, but when stacked layer by layer, they form a stable "wooden pizza tower," reflecting the holistic thinking of Chinese architecture - building the whole from countless small parts. This approach often strikes a chord with overseas audiences as well.

When speaking to foreign viewers, Wang often begins with a question: In the oldest church or the most ancient marketplace in your hometown, is there a brick or stone that carries the lives and memories of generations? Only then does he turn to dougong.

"Mortise-and-tenon joints represent Eastern ingenuity, but what truly allows buildings to endure for a thousand years is never the structure alone, it is the generations of people who remember the 'warmth in their palms,'" he noted.

Wang recalls one occasion at the Hall of the Holy Mother at Jinci Temple in Taiyuan, when a young American followed him in assembling a dougong model. After finishing, the visitor exclaimed, "It feels less like an object and more like a symphony of wood."

During livestreams, Wang often points to the patterns of light and shadow cast by the brackets and says, "Don't these grids look like codes the ancients wrote to the sky? Every mortise and joint are a dialogue with time."

It is these seemingly casual yet poetic expressions that transform dougong from a mere "structure" into a "language," turning ancient architecture into a gateway to cross-cultural understanding.

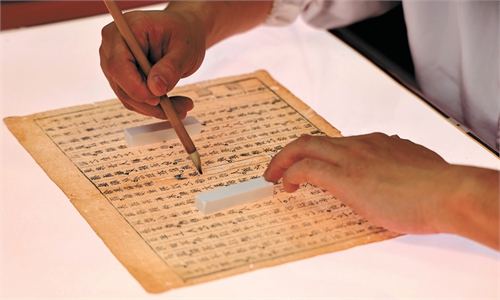

Wang Yongxian measures a structure of an ancient building Photo: Courtesy of Wang Yongxian

An academic path

If short videos have brought Wang wider public recognition, what truly underpins it all is decades of sustained scholarly accumulation and fieldwork practice.

Wang produced a complete annotated translation and systematic interpretation of the Song Dynasty classic Yingzao Fashi, constructing a comprehensive theoretical framework for the study of ancient Chinese architecture through more than one million words of writing.

According to Wang, he has participated in surveys and key restoration projects involving tens of thousands of historical buildings across Shanxi Province. To obtain firsthand material, he once spent two years painstakingly copying nearly 1,000 square meters of ancient murals in Shanxi.

From Pingyao Ancient City's successful World Heritage application to a series of major cultural relic protection projects, his long-term, quiet dedication can be found behind many of these achievements.

Zhang Yin, a cultural relics and archaeology expert, told the Global Times that Wang Yongxian is not an isolated case. It is precisely this generation - ancient architecture practitioners who have spent years walking along beams and working through wind and rain - that forms the "invisible support" enabling China's architectural heritage to endure to this day.

"They are often little known to the public; yet through surveying, restoration, documentation and research, they accumulate knowledge inch by inch," Zhang noted.

"Buildings will grow old, but the memory of looking up at a tower's shadow will not," he said.

What Wang safeguards is not only dougong and ancient architecture themselves, but also an emerging possibility, one that brings those long hidden beams and blueprints into public view, and allows people centuries from now to still draw close to the wood and feel the warmth that has yet to fade.