ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Millet staple food in ancient Lüliang 2,000 years ago: archaeological analyses

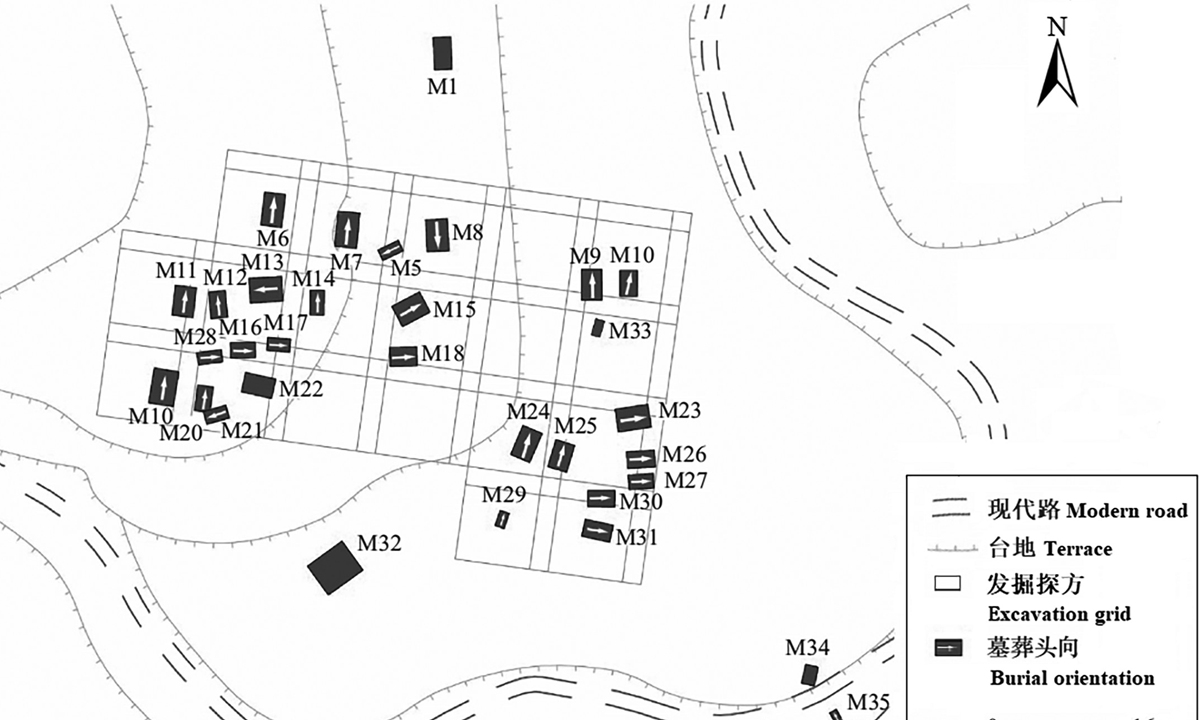

Map of the Houshi Cemetery Photo: Courtesy of Wang Xin

Ancient communities living in Lüliang, North China's Shanxi Province relied primarily on millet farming and experienced significant population movement and cultural mixing during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770BC-256BC), according to new scientific archaeology research.The findings, announced by the Shanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, are based on chemical analyses of human bones and teeth excavated from the Houshi cemetery in the Lishi district of Lüliang city.

Located in the core of the Loess Plateau, the Lüliang area served as a geographical and cultural link between the northern pastoral nomads and the Central Plains. By analyzing the human and animal bones unearthed from the Houshi cemetery, researchers aim to reconstruct the diet of the local population and identify potential immigrants during the Eastern Zhou period.

The research was conducted by a multidisciplinary team led by scholars from the Shandong University. By analyzing stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes in bones, they reconstructed ancient diets, while strontium isotope analysis of teeth was used to trace individuals' places of origin. Additionally, a small number of animal tooth samples from the nearby Xinyi site were analyzed to establish a more precise local range of strontium isotope ratios.

Results show that most individuals consumed a diet dominated by C4 plants, a category that includes millet and broomcorn millet. This indicates that millet agriculture was already well established in the area during the Eastern Zhou period, while animal husbandry played a relatively minor role, Wang Xin, leading author of the paper, told the Global Times on Tuesday.

"The chemical signatures clearly point to millet as the main staple food," Wang said, adding that the findings reflect the strong influence of Central Plains' agricultural culture as the Jin state, and later the Zhao state, expanded northward. Jin and Zhao were two states that existed during the Eastern Zhou period.

The Houshi cemetery, covering about 30,000 square meters, was discovered during an archaeological survey for a highway relocation project in late 2019 and excavated in 2020. Archaeologists uncovered 40 tombs, most dating to the Eastern Zhou period, along with pottery, bronze and iron objects, jades, stone tools and bone artifacts.

Based on burial orientation, burial style and grave goods, researchers said the cemetery reflects a mix of cultural traditions, including those associated with the Jin and Qin states as well as northern nomadic groups.

Strontium isotope analyses identified at least four individuals who were not born locally. Two of them were buried in a flexed position or with head orientations different from local norms, suggesting they may have come from other cultural or ethnic groups.

By combining burial evidence with carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses, researchers found that some individuals with unusual burial orientations or practices had diets that differed from those of most people at the site, while others with distinctive burial customs showed no dietary differences.

The findings suggest that some individuals retained burial traditions from their original cultures while adopting local eating habits. These may have included members of minority groups, as well as people from the Qin state who moved into the area during the late Warring States Period (475BC-221BC) as Qin influence expanded eastward.

According to Wang, during the Eastern Zhou period, the Lishi area was shaped not only by the expansion of Central Plains states and their agricultural traditions, but also by its position at the frontier where the Jin and Qin states met northern peoples. As a result, the region experienced active population movement and multi-ethnic interaction.

"The study offers a new scientific perspective on how exchanges between the Central Plains and peripheral regions contributed to the formation of early Chinese civilization," noted Wang.