Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Commenting on a certain international maritime dispute, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said, "this is an important decision, it is one that has been made in accordance with international law and it should be respected by both parties, and indeed by all parties and all claimants." It's a shame his foreign minister doesn't seem to agree.

Following the announcement of The Hague ruling on the South China Sea dispute between China and the Philippines, Australia was all too quick to condemn what it regarded as regional "bullying" in violation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and urged China not to pursue bilateral treaty agreements in lieu of a multilateral resolution.

Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop also reaffirmed Australia's commitment to exercising its rights to freedom of navigation. In her own words, to ignore the ruling would be a "serious international transgression," and that Australia would stand with the international community in calling for both sides to treat the arbitration as final and binding.

That opinion might have been taken more seriously if Australia followed up on its hollow commendation for multilateralism and international law with adherence to those ideals itself.

Australia has had its eye on Timorese oil for a while. Having endorsed the 1975-99 Indonesian occupation of East Timor during which up to 180,000 soldiers and citizens were killed, Australia was complicit in atrocities, and the only Western nation to recognize Indonesia's annexation of Timor-Leste - a means to an end, ensuring the ratification of the 1989 Timor Gap Treaty.

This treaty, famously celebrated with an in-flight champagne toast between then Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans and Ali Alatas, the Indonesian foreign minister and representative of "friend of the West" president Suharto, opened the Timor Gap to Australian and Indonesian exploitation. This left Timor-Leste without a permanent maritime border.

Most recently, the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS), which Australia argues is the legal basis for its claims, was signed in 2006. This treaty is virtually equivalent to the 1989 treaty, except that the ratio of revenue distribution in the Joint Petroleum Development Area was changed in favor of East Timor to 90:10. On these grounds, Australia argues that its bilateral treaty with Timor-Leste is "fair."

This ratio is, however, based on a disputed definition of Australian borders which places the bulk of the Greater Sunrise gas field - 450 kilometers north-west of Darwin, or 150 kilometers south-east of Timor-Leste - in Australian territory. Amid tensions over the distribution of revenue, it was revealed that Australia had spied on treaty negotiations in 2004 under the guise of an aid program. It is yet to be tested whether this espionage is legally equivalent to fraud, a ruling which would invalidate the treaty.

The father of East Timorese independence, Xanana Gusmão, urged his Australian counterparts to "sit down as friends and negotiate," while the Australian government has explicitly rejected any ruling that may result from the arbitration that Timor-Leste has called for on the grounds of Australian fraud, and refused to participate in any such negotiations.

Australia argues that the commission does not have jurisdiction to conduct hearings on maritime boundaries. And, technically, it doesn't.

Australia lodged a declaration in 2002, just months before Timor-Leste declared its independence, stating that it does not accept the procedures provided in UNCLOS for resolution of maritime disputes. In other words, Australia does not recognize the legitimacy of any Hague ruling, nor is there any mechanism for implementation of any recommendations that may arise as a result of the arbitration.

Sound familiar? Like the South China Sea arbitration, there is an existing agreement that a single party retrospectively disputes. In 2006, China made a similar statement excluding itself from dispute settlement procedures, pursuant to Article 298 of UNCLOS.

Concurrent to its condemnation of China's preference for bilateral negotiations with the Philippines, and its criticism of Japan for withdrawing from UNCLOS in order to allegedly pursue whale slaughter, Australia exempts itself from the very conventions it cites in denouncing other nations' supposed violations of "international law."

Unfortunately, Australia's regional bullying and the embarrassing revelation of covert spy operations overshadow its otherwise admirable aid efforts in Timor-Leste.

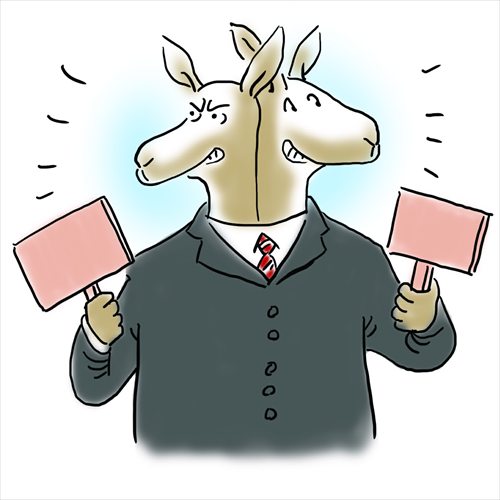

What's more perplexing is Australia's brazen hypocrisy, reflected in its blatant double standards on international law. Bishop previously cautioned China on the "reputational cost" of ignoring the Hague ruling, a ruling that Australia does not recognize itself. Perhaps Australia should heed its own advice before calling the kettle black.

The author is a Shanghai-based Australian scholar and commentator. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn