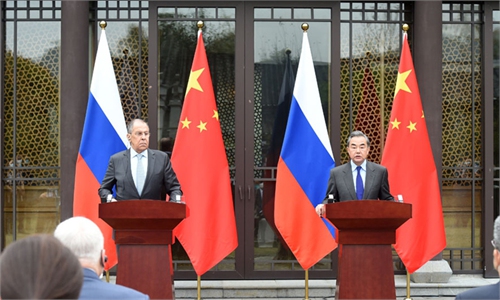

Photo: Xinhua

Throughout the 20th century, strategic wisdom dictated to US statesmen never to allow the world's island - namely, the Eurasian continent - to be dominated by one hegemonic power, or a single alliance. This logic brought the US into the World War II. Germany was then seeking the domination of Eurasia from the west with Japan coming in to control it from the east.Similar logic operated during the Cold War. To dilute, and then derail the Soviet-Chinese alliance, the US began to engage China from the mid-1950s, even as it reached out separately to the Soviet Union. Washington's policies were crowned with success in the 1970s, when it boasted better relations with Beijing and Moscow than those two capitals had with each other.

The end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet Union, however, encouraged strategic arrogance in the US. In vain, Russia's Westernizing liberals who were losing ground domestically in the 1990s tried to scare Americans with a specter of Russia's tilt toward China in case NATO's eastern enlargement continued and Moscow was being left behind.

Even when the tilt turned into reality, most Americans remained unperturbed. The hubris was easily explained by the dizzying sense of tremendous power and the absence of rivals during what became known as the "unipolar" moment. Russia was thought to be a has-been power in terminal decline; China, though rising, was expected to integrate itself economically, and then strategically, into the US-led system, where it was offered a position of a responsible stakeholder.

Moreover, many saw Russia as having little to offer to China, and fearing it for geopolitical, cultural, psychological, and a host of other reasons. Mainstream US analysts spent two or three decades waiting for an inevitable clash between Moscow and Beijing: whether in the Far East, Central Asia or elsewhere. These analysts were also convinced that both China and Russia were exceedingly focused on the West and looked at their own bilateral relationship as just a temporary marriage of convenience.

Early in his tenure, former US president Donald Trump briefly sought to change this attitude. In order to fully focus on China that he regarded as the principal rival for the US, Trump fancied getting along with Russia whom he did not see as a competitor. This, however, did not work due to the virulent opposition from the Democratic Party and its allies in the mainstream media who painted Trump as a de facto "Putin agent."

Now, the Joe Biden administration faces two major powers which it officially brands as adversaries. China is considered the principal economic and technological challenger to the US, while Russia is taken as a threat to domestic stability in the West, including in the US itself. With "America is back" as a rallying slogan, President Biden has started a geopolitical offensive. Washington's objective is reasserting US global dominance, fighting off the Chinese economic/technological challenge and Russia's military/political one. Under the plan, Beijing and Moscow would be contained and put under pressure from the outside as well as from inside their own societies.

The strategy calls for the consolidation of US-led alliances in Asia and Europe, and their expansion through additional partnerships. Senior members of the Biden administrations have made early visits to the US allies in the Indo-Pacific and then the Euro-Atlantic regions. The president himself has directly engaged with leaders of the Quad and the European Union. The Five Eyes - Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the US - emerges as the core of the US system of alliances, its inner circle. America's political bonds with major advanced economies are key for raising the effectiveness of economic and technological sanctions against its rivals.

The other axis of the strategy is pressuring China and Russia domestically and in their immediate neighborhoods, by using the pretexts of democracy and human rights, as well as ethnic issues and nationalist tensions. There, the Biden administration exudes confidence of being able to use democratic America's advantages.

China and Russia are responding by coordinating their own policies more closely; expanding their cooperation to include new areas, from domestic politics to the cyber world and outer space; and by reaching out to the global community stricken by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Will the US strategy succeed? For all the power and influence of the US, its policy has a number of weak points. The emphasis on democracy versus authoritarianism may not work in the world where real issues are not ideology but governance, stability and prosperity. It should be noted that the recent experience with COVID-19 and the anti-virus vaccines has not shown the US as a clear winner. Moreover, ideology is not well suited to pragmatic alliance policies, which dilute it. Important economic interests continue to link many US allies and partners to China, and some to Russia, promising serious friction with the US over too stringent sanctions. Finally, few countries among US allies and none of the key ones are looking forward to a new bloc-based division of the world.

It may be expected that Russia and China, seeing all this, will engage with their main economic partners in Asia, Europe and the rest of the world to raise those countries' stakes in the relationships with Moscow and Beijing, thus both countering the US common front strategy and preventing the world's Cold War-style split into two camps.

The author is director of the Carnegie Moscow Center. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn