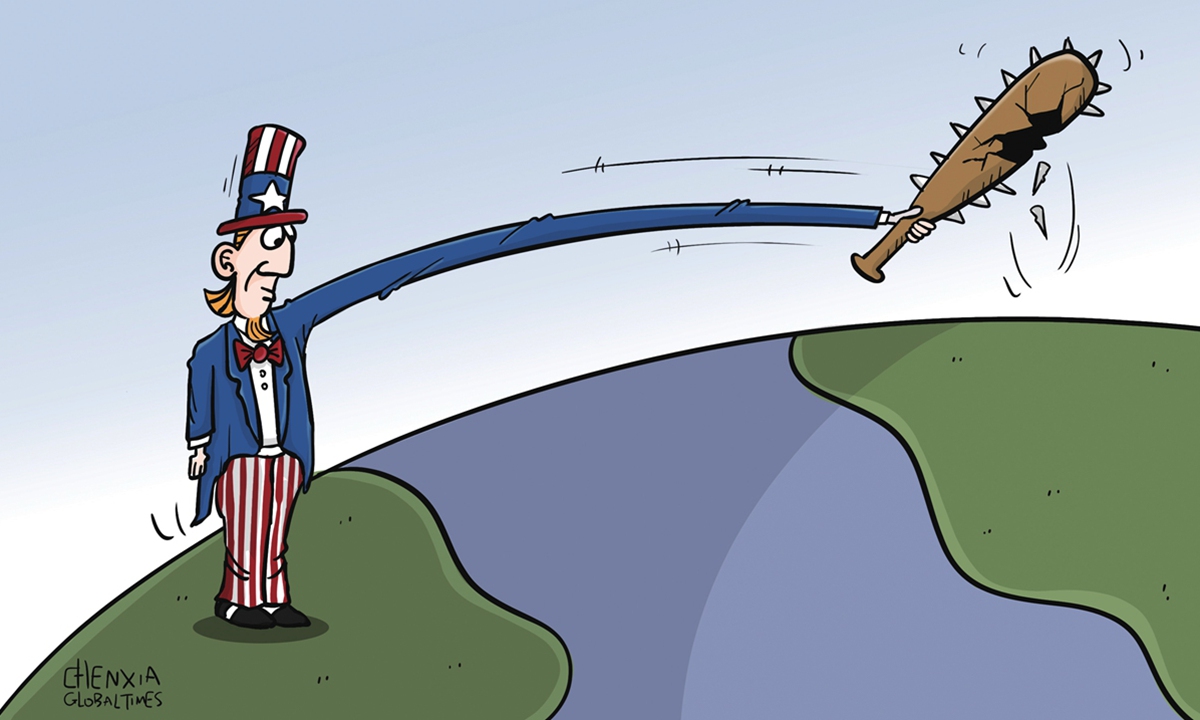

US sanctions Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

The US has become overly addicted to sanctions. Over the years, scholars and observers worldwide, even those from the US, have raised concerns about it. According to The Treasury 2021 Sanctions Review, released by the US Department of the Treasury earlier this month, US Treasury's use of sanctions has increased by 933 percent over the past two decades, from 912 sanction designations in 2001 to 9,421 this year.

"In theory, superpowers should possess a range of foreign policy tools: military might, cultural cachet, diplomatic persuasion, technological prowess, economic aid, and so on. But to anyone paying attention to US foreign policy for the past decade, it has become obvious that the US relies on one tool above all: economic sanctions," wrote Daniel W. Drezner, a professor of international politics at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University on Foreign Affairs.

Statistics from the Global Sanctions Database show that the US has been the most frequent user of international sanctions in the world since 1950. Former president Donald Trump pushed the trend to its peak. The Trump administration imposed sanctions "at a record-shattering pace of about three times a day during the president's time in office," Bloomberg reported.

This may explain the reason when the news came out that the Biden administration planned to limit the use of economic and financial sanctions, it attracted a lot of attention and speculation about "why."

More pain than gain

Economic sanctions are generally restrictions or bans that one country imposes on another. The goal is to cause economic harm in the targeted country until it obeys the sanctioning side.

Yet the tool is not cost-free. Over the years, the US has also been haunted by the sanctions it has wielded. Take tariff wars, it is US companies and consumers who pay for the most of additional costs caused by policies.

Moreover, sanctions are hurting US' image in the global arena for bringing serious hardship to civilians in targeted countries, turning US rivals more hostile toward Washington, and straining ties with allies, like in the case of the Nord Stream 2.

And the US now has to confront a harsh truth: It is no longer capable of ignoring the side effects on itself from wantonly using the sanction stick.

Take a look at the US economy. Even the word "sluggish" is not enough to describe how bad it is. Inflation is running high, the supply chain is stuck in a crisis, the shortage of goods is spreading, and the debt ceiling has been raised time and again. The US government is literally running out of cash to pay its bills. "How can Washington possibly impose more sanctions when the US own economy is in such a mess?" asked Shen Yi, a professor at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs of Fudan University. Shen told the Global Times that against this backdrop, if the US truly wishes to turn the tide of its domestic issues, it has to cooperate with other major powers.

There was a time when the US was strong enough to sniff at the adverse effects of using sanctions. But it is no longer what it was, especially when facing a strong rival. If the US government ever attempts to decouple with a certain country with deep economic integration with it, and hurts US domestic capital forces, let's see how much suffering the administration will have to face, Shen said.

Dollar decoupling

Perhaps the biggest nightmare of the US Department of the Treasury is a possible worldwide decoupling from reliance on the US dollar. As the department's review mentioned, "American adversaries - and some allies - are already reducing their use of the US dollar and their exposure to the US financial system more broadly in cross-border transactions. While such changes have multiple causes beyond US financial sanctions, we must be mindful of the risk that these trends could erode the effectiveness of our sanctions."

The US is hesitant to admit it, but it is the truth - countries' reduction of their use of dollar is to a large extent caused by US sanctions.

In June, Russia's Finance Ministry noted the country will completely remove the dollar from its rainy day fund, in an attempt to reduce sanctions risks.

In January, the European Union also set out plans to curb reliance on the US dollar as a move to "reduce vulnerability to US sanctions in the wake of battles over Iran policy," the Financial Times reported.

The strength of US sanctions comes from the dollar's hegemony. How long can the US keep up its bossy manner when a growing number of major powers jointly boycott the privilege of dollar due to US sanctions?

Policy adjustment

Do US sanctions work? There is an obvious watershed. Those target at US "little brothers," the more obedient the latter is, the wider gap there is with the US in national strength, the more successful the sanctions could be. But when it comes to US rivals with a firmer will to resist, and less illusion toward Washington, the sanctions are less likely to succeed, according to Shen.

One example is US sanctions against Japan in the 1980s. The long-lasting trade war led to a 10-year period of economic stagnation, dubbed the "lost decade."

Other successful cases of US sanctions can only be found among US allies. Take Alstom, once the brightest pearl in French industry, which was dismantled by the US. The US may have won a temporary victory in those cases, but it is losing faith little by little from its allies.

Direct failures are easier to find. Take Russia, North Korea, Cuba and Iran. The US has piled huge pressure on them for decades. Indeed, they paid a great economic price, but no change has been made in their national policies or behavior as the US expected.

"For a country with strong enough political will, US economic sanctions' ultimate goal may never be achieved," Shen noted.

Unfortunately, the Treasury Department's review did not touch upon the limitations of US sanctions. It's more like a paper defending the sanctions, saying economic and financial sanctions "remain an effective tool of US national security and foreign policy now and in the future." It makes some suggestions, though, such as "where possible, sanctions should be coordinated with allies."

In the end, the superpower merely wants to reduce the cost of sanctions when catching its breath after splurging on its hegemonic resources for too long. Washington will cut the number of sanctions, but will try to improve the efficiency of the stick, Xu Liang, an associate professor at the School of International Relations at Beijing International Studies University, told the Global Times.

However, from US withdrawal from the Middle East to the adjustment in sanctions policy, Washington is proving one thing - the US is no longer the hegemonic power that can boss countries around at its will.