US flag and the statue of liberty photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

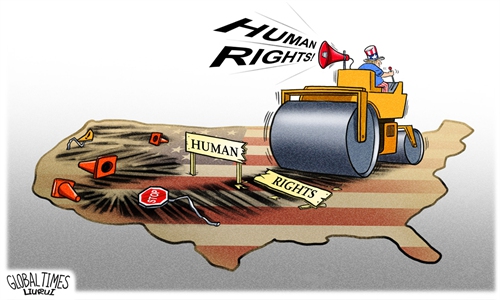

When asked about Washington's notorious Guantanamo Bay prison, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian said on Friday that it "has fully exposed the hypocritical double standard of the US on human rights issues." In fact, while ignoring its own abuses, the US has weaponized human rights issues to smear and attack other countries. Why does the US feel threatened by China? How will the struggle over human rights between the US and other powers, such as China and Russia, end? Global Times (GT) reporter Xia Wenxin spoke with James Peck (Peck), a US scholar and adjunct professor of History at New York University.

GT: You have pointed out in your book Ideal Illusions: How the US Government Co-opted Human Rights that the anti-China faction within the US government still believes today that human rights are the last ideological weapon against China and a project that will bring doomsday to the Communist Party of China (CPC). Has the US achieved the results it wants by using human rights to attack other countries, especially China, and interfere in their domestic affairs?

Peck: The results have been mixed. To those hawks I wrote about, human rights constituted the ideological core of democratization, of US soft power, of the "rule of law." They spoke of American universality and how such rights could largely be judged by the US apart from any particular economic and cultural contexts. The problem, as the late US political scientist Samuel Huntington put it, was that what such universalism was to the West was imperialism to the rest.

Regrettably, the orchestration of human rights attacks has been effective in mobilizing an unfortunate mistrust and misunderstanding of China in the United States. But this is not quite the same as saying it is similar to the Cold War period when a frightening anti-communism in the US blended with manipulated fears of the USSR. No such direct internal/external dynamic is in existence now. Public opinion polls suggest a negative view of China in the US, but public concern with China (as opposed to elite manipulation of the issue) is far less intense compared to a long list of other pressing problems that concern the American public. That doesn't mean making China America's "enemy" isn't in the works, but it's going to prove a far more complicated and contradictory dynamic than existed through much of the Cold War decades.

GT: You wrote in 2021 that "America's greatest existential threat today is not China; it is making China into America's existential threat." Why does the US keep portraying China as an existential threat? How did the hostility toward China develop in American society?

Peck: Throughout my life, I've seen China depicted as an outright threat or with deep uneasiness. The US has never, in the end, quite known how to accept China, its revolution, its civilization, or its insistence upon pursuing its own independent path. And a "threatening" China has always been tied with how the US has sought to become and remain the predominant power on the planet, the center of the capitalist system it was so instrumental in refashioning after World War II.

Until recently, few in Washington expected the astonishing transformation of China - its economic prowess, its rapid urbanization without slum cities, its scientific and technological prowess, the education of its vast population, its modern infrastructure which is the envy of much of the world, and its continually evolving pattern of governance that has enabled these developments - has stunned US leaders. That all this has taken place under the leadership of the CPC has frightened most US leaders and left them unable to envision any positive reasons for this outcome. In earlier times, numerous US leaders thought a China drawn into the world capitalist system would find itself, like so many other countries, changing in ways that would limit its independence and shape how its economic and political system would develop. But China's size, cultural density and sophistication, its long continuous history, and its dynamic experimental system of governance led by the CPC, have ended up with results Washington never really expected.

The outcome has been a very different China than anything Washington has confronted before - an extraordinary non-Western civilization moving to the center of global power. Nothing in US history has quite prepared for this situation; not politically, culturally, psychologically, racially, or strategically. Today, with China the world's largest exporter, a financial powerhouse and global investor, a main trading power for a large number of nations throughout the world, its example of successful development and ways of governing itself - all this supports a greater range of choice for nations long locked into the embrace of "the West."

In this changing world, Washington once again can't quite cope with an accurate image of China and the reasons today are analogous to why the US refuses to accept a multipolar world. China's independence, and the efforts of other nations in the South to find their own independent ways, arduous as they are, ultimately are not compatible with Washington's intensely ideological American-centric globalism. In the end, a view of China as part of an emerging multipolar world, and not simply as the US-depicted frightening superpower, provides a far more accurate context for understanding what has for so long been grossly distorted by America's global agenda. In the future, there will be no superpower in the American model. The needed changes may be coming, but Washington continues to fiercely resist them. It would rather focus on China than the realities of the world it now confronts.

Can this change? Possibly. I'm hardly alone in the US in thinking that no critical domestic issue or global peril is going to be effectively dealt with by Washington's escalating hostility toward China and Washington's continued denial of what a multipolar world really entails. There is a deepening understanding in the US of the catastrophic possibilities of climate and environmental devastation, global pandemics, economic upheavals, and the dangers deriving from the current lack of global governance that requires finding just ways to deal with such problems. Regrettably, the US is allowing a host of lesser issues to stand in the way of what needs to be done. But certainly, existential realities are beginning to register more and more among Americans.

GT: A Russian scholar said that globalism under the leadership of the US has turned into a machine that destroys humanity in a recent interview with the Global Times. Since you have also used the term "American-centric globalism", in your opinion, how has globalism under US leadership impacted the world today? And what kind of globalism does the world really need?

Peck: Globalism under US leadership has indeed sought to build an American-centric worldview that remains an existential threat to the diversity of ways that countries need to find to develop and govern themselves. In fundamental ways the US can't accept a multipolar world; indeed it has often struggled against it and the dynamic openness it requires apart from a dominating US-centered globalism.

All this I think underlines once again how it is essential to speak of humanity without insisting upon a universal ethos. Humanity has played out its destiny in a diversity of languages, a diversity of moral experiences, and a diversity of spiritualities and religions. Humanity, in reality, is irreducibly plural. On the technical and scientific level, it is relatively easy to communicate. Yet on the deeper level of historical creation, diverse civilizations need to communicate with each other with an appreciation that cultural differences are a constant source of enrichment for humanity.

China is far more at home in such a world than is the US. Part of the reason has to do with how little the US thinks it has to learn from others, and this obviously includes China. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said: "The essence of Western arrogance is the belief that it has everything to teach others, and nothing to learn from them."

GT: You have a book that will be published, titled "Misunderstanding China: Why Washington Gets it Wrong." Could you tell us about your views and main findings in this book? In what aspects is Washington misunderstanding Beijing? Why does it happen?

Peck: As my earlier comments suggest, part of my work examines why, since the 1940s, Washington strategists have never gotten China right. For over 70 years they have crafted various global strategies that were then refracted through a conception of China. Washington strategists feared China, condescended to it, reacted with incredulity at times to Chinese developments, sought to make Beijing a globally responsible "stakeholder" - many hoping to "change China" in ways it favored. But each strategic assessment was seriously flawed - revealing far more about Washington's vision of the world than Chinese realities.

At the same time, I seek to place such questions in places other than a strategic, geopolitical setting and show how Washington's power operates. I'm exploring what keywords, concepts and ways of thinking are appropriate to compare and contrast Chinese civilization and the history of the United States. So many Western terms don't really fit China's history and civilization. Nor should they be expected to do so. Discussions in China in recent decades offer probing, thoughtful, and diverse ways to understand China and its civilization often in comparison with the West - in the process, breaking out of a Western centrism that has long limited and at times grievously distorted China. I have learned much from them.

To cite an obvious challenge. I live in a country where the words "Communist Party" are largely thought-stopping words. To argue that what China has accomplished is intimately tied to the leadership of the CPC and how it has evolved over the years is to open yourself up to an updated version of what those Americans in the 1940s and 50s went through when they spoke against the omnipresent hostility toward "Communist China."

Part of the problem lies in how the CPC is like no other political party in the world - and that its accomplishments are a reflection of this. The absence of appropriate concepts, frameworks, keywords about China in the West often precludes any understanding of why the CPC became central to the solution to China's problems instead of standing in their way; why China has not adopted Western systems of governance, but sought its own; why and how the CPC evolved its developing patterns of governance out of a distinctive set of historical, revolutionary, and core aspects of Chinese civilization. And more: how the CPC has sustained national unity and a stability today that enables a rapidity of prolonged change like no other nation has ever undergone.

Words matter. Finding more insightful ones that break out of a sterile, imprisoning Western centrism remains a critical task.

GT: Countries like China and Russia have stepped up their efforts to take countermeasures against attacks on their human rights situation by the West, especially the US. This includes exposing Washington's own human rights problems. How do you think this struggle over human rights will change? Will the US suffer from backlash?

Peck: This is a particularly dangerous, volatile moment in American history. How the US uses human rights language will almost certainly be affected by this. US human rights strategies have long blended in with democratization and electoral systems as ways to judge and challenge others. Yet given its increasing domestic divisions, the enormity of its racial divisions, domestic governmental paralysis, a plutocracy committed to ever increase its wealth - all this is starting to prove corrosive of the idealism and moralism which the origins of the human rights movement required in the US.

This is just beginning to change. But my sense is that the language of effective governance, equity, social justice is slowly going to replace some of the primacy of human rights language. All this requires putting human rights in a very different, less ideological context, a development that is long overdue.