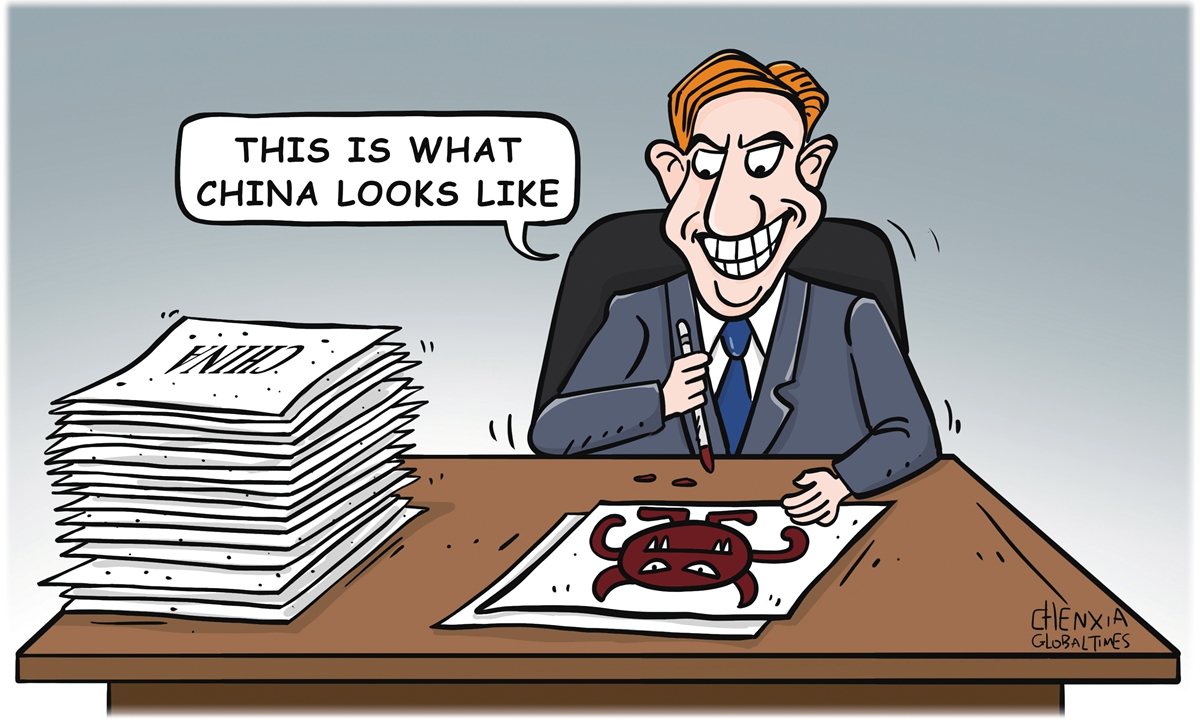

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Editor's note:

The hysteria toward China has risen to a new peak in the US. Political climate in Washington is increasingly weird in terms of China-related topics. Why is there so much irrationality on China in the US? How to view China-US relations from a constructive perspective? The Global Times interviewed several Chinese and American observers on these topics.

The following is an interview conducted by the Global Times (GT) with Da Wei (Da), director of the Center for International Security and Strategy of the Tsinghua University in Beijing. This is the first interview in the series.

GT: What's the reason for the irrational voices within the US in terms of the domestic environment?

Da: Prior to Biden's presidency, a basic consensus had developed within the US on the perception of China as a strategic competitor or, to put it less mildly, a challenge or threat to the US. A more hostile view of China's domestic political trend had also developed within the US, namely that China was at least a technological authoritarian state. The judgment that China "poses a threat" in terms of the size and political nature of the country is already a mainstream view in the US. It is difficult for any administration to overturn, but can only be adjusted under the existing conditions. Compared to the Trump administration, the Biden administration has had some high-level dialogues with China, despite the limited room for policy adjustment.

Of course, the Biden administration is not actively trying to adjust the perception. But objectively speaking, the adjustment demands an opportune moment and a long period of time, leaving the Biden administration's China policy limited room for maneuvering. As a result, the US government and academia have been quite aggressive in their rhetoric toward China, all because of the US strategic consensus on China that has been formed and increasingly consolidated.

Within such a framework, domestic voices in the US tend to believe that there are less cooperation fields benefiting the US. Those voices began growing bigger from around 2010 and became mainstream during the Trump presidency, when he imposed a series of sanctions against China and started the trade war. China had to fight back in the face of US repression, thus creating a "wartime-like" atmosphere. At the beginning of a war, there may be anti-war opinions on all sides, but after the bullet is fired and everyone's emotions get fierce, there are less rational voices. The same is true between China and the US, as the voices within the US that advocate détente with China have further diminished in the wake of the 2018 China-US trade war. People with rational views are not always willing to speak out in this climate due to various concerns.

GT: Is there any opportunity in the future to reverse or at least improve such climate? With this perception, how much room is there for the voice of reason within the US?

Da: In the short term, I do not see much opportunity for a turnaround, because a shift in understanding will have to wait until relations between China and the US ease and the general environment changes, and there will be room for different voices to be active only after policies soften. For example, before Henry Kissinger's secret trip to China in 1971 and Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972, there were some rational voices in the US that wanted to improve China-US relations which, however, were still in the minority. It was only after their visits to China that the door to China-US relations was opened and the two countries began to interact in a healthy manner. The climate has significantly improved since then, which in turn has driven a change in public opinion.

When expressing their views, people are influenced by their surroundings, which are largely shaped by government policies. Therefore, the change of public opinion depends on whether both governments can release enough positive signals to develop the relationship. Sometimes when the government moves one inch forward, public opinion will respond by moving one foot forward, broadening the space for governments to make further changes. In other words, government policies and public opinion are in constant interaction and interplay. Public opinion can limit the role of governments, and the policies can widen the space of public opinion. Therefore, the role of political leaders becomes critical. If they find opportunities to break the ice in a limited space, as Chairman Mao Zedong, Premier Zhou Enlai, President Nixon and Mr Kissinger did, taking a small step at a critical moment, they may open up considerable space for China-US relations. But for now, it seems that the Biden administration has little incentive to change such a mainstream consensus.

GT: In general, the US has become increasingly sensitive to the so-called "China threat," including using the Ukraine crisis to hype the Chinese mainland's ability and potential to reunify Taiwan island force, and continuing its McCarthy-style purge of "Chinese espionage." Is it possible to reverse such a mentality?

Da: I'm afraid that this mentality cannot be reversed because two basic facts cannot be changed. First, as the world's second-largest economy, China has now developed into a relatively powerful country. Second, China is a country led by the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Party is strengthening its leadership. Neither fact is what the US wants to see. As a result, it will stubbornly cling to this idea.

GT: What to make of the frequent US narrative comparing China and Russia, Ukraine and the Taiwan island?

Da: It seems that some pundits and officials in the US are losing their ability to analyze China in a more nuanced way. There seems to be a decline in the number of China hands in US younger generation and among some officials now in power who are able to rationally analyze the nuances in China-related issues. In addition, due to the deterioration of China-US relations, scholars are less willing to conduct nuanced analyses and instead take a more facile approach to describe the current situation.

The US is a country that cherishes and emphasizes values. The dark side of it is the US tends to view other countries from an ideological lens. The similar mistakes happened throughout its history repeatedly. In the Vietnam War, for example, one of the basic mistakes the US made was that it failed to understand the fundamental goal of the communist in Northern Vietnam. The Americans saw the efforts of the North Vietnamese to unify the country as a part of the so-called "communist expansion." And US policy makers at the time believed, based on the "domino theory," that if the Communist Party of Vietnam could not be prevented from unifying the country, perhaps the whole of Southeast Asia would fall into Communist camp. However, the primary purpose of the Vietnamese revolution was to fight for national liberation and independence, rather than ideology expansion or export of revolution. By equating Vietnamese Communist party with the Soviet Union, the US efforts in Vietnam ended up in the quagmire of the Vietnam War tragically.

On the issue of China, as early as the 1960s, some Americans began to discuss and compare the dueling of China and the Soviet Union. At the beginning, it was difficult for Americans to understand why the two parties would break up and even go into hostility and conflict. During the discussions, the US gradually came to the conclusion that although both countries established socialist systems, China could not be equated with the Soviet Union and the CPC could not be equated with the CPSU. This conclusion became the mainstream view in the US, especially after the 1980s.

However, such a nuanced analysis, on one hand, was based on the expertise of the China hands in the US back then. On the other hand, the relations between China and the US were indeed moving forward, which made room for such a detailed comparative analysis within the US. But what we see today is that the US is again equating China and Russia, two countries that have good relations but cannot be equated in any way, or repeatedly comparing the Ukraine issue with the Taiwan question, two issues that seem to have slight similarity on the surface but in reality are not comparable at all. Once again, the US is losing its expertise and willingness to understand the nuances of international issues, leading to this very dangerous phenomenon now.

Moreover, when someone regards their opponent as the main threat or enemy, it is least likely that the opponent will be judged carefully and rationally, but rather crudely omitting the complexities within and differences between different objects, such as China and Russia.

GT: Will this prolonged loss of expertise and nuanced analysis result in the destruction of the legacy of China hands in the US?

Da: The US still has a lot of China hands, but at present it seems the US is seeing less humanistic input into the study of Chinese history, culture and even art and philosophy, while more experts on China in the social sciences are emerging. One of the outcomes is that fewer American experts are willing and able to understand China on the basis of empathy.