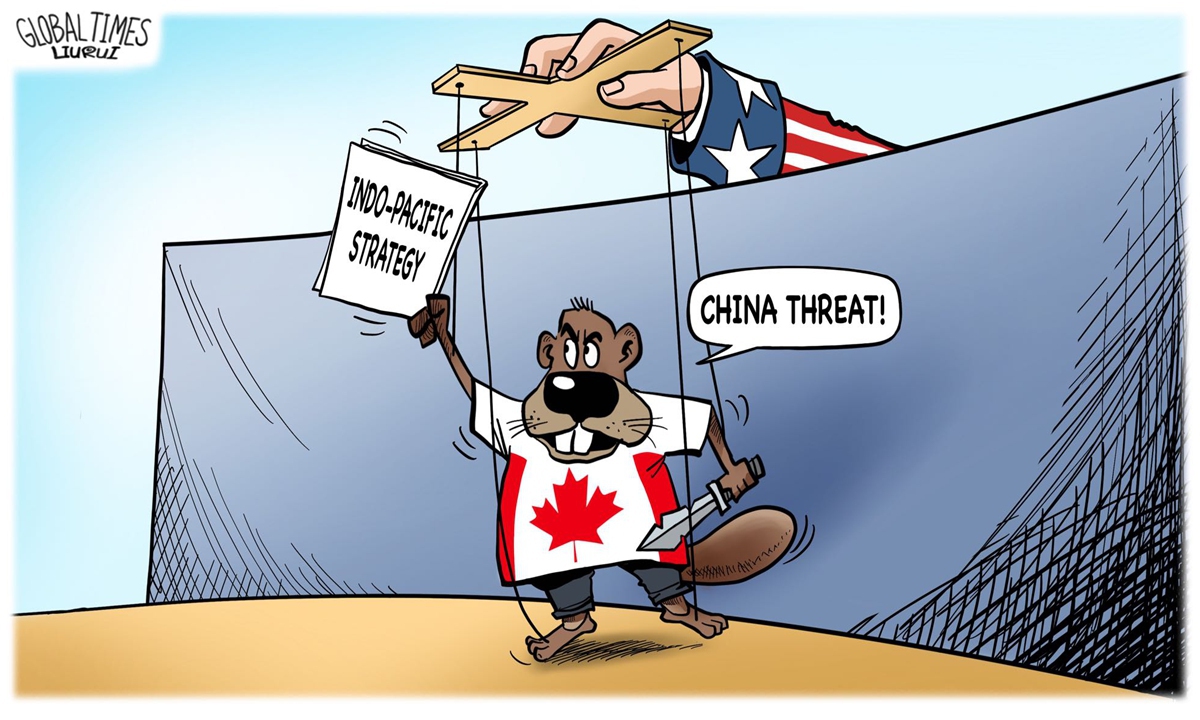

Illustration:Liu Rui/GT

Canada unveiled its long-awaited "Indo-Pacific" strategy by the end of November, just about one month after the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The document described China as "an increasingly disruptive global power," mentioning it more than 50 times, signaling a tougher approach on Beijing.In response, China's embassy in Canada stated that the strategy "exaggerated the so-called China threat… China is deeply concerned about this and firmly opposes it." In addition to the apparent message that tensions between China and Canada since 2018 are not about to get better anytime soon, it requires us to look beyond the current setbacks of the relationship. More in-depth, broader and practical implications of Canada's 26-page strategy must be addressed.

First, the distorted truth in this strategy threatens regional inclusivity, and is hence unpopular among regional countries. Using negative language, the strategy says, "China's rise, enabled by the same international rules and norms that it now increasingly disregards... increasingly focused on bending international rules to suit its own interests." Such charges are misplaced as Canada assumes Chinese motivations and intentions are in line with their own worldview of a Western-led security order.

Actually, China has all along upheld the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, defended the UN's central role in international affairs and served as a firm builder of world peace, a contributor to global development, and a defender of the international order. China made it very clear that the international order it supports has the UN at its core and underpinned by international law and the basic norms based on the purposes and principles of the UN. China considers this order as the "true spirit of multilateralism," in contrast to unilateralism, which erects walls and barriers and pursues decoupling.

Imposing the rules made by a particular country or group on others not only fails to reflect the geopolitical situation and reality in the so-called Indo-Pacific but also becomes the antithesis of multilateralism, which harms regional inclusivity. What's worse, those who are undermining international order based on international law, and damaging sovereignty of other countries, are the real "disruptive power" who poses challenges to regional peace, security and development. For regional countries, China is a security provider and not a security recipient. They are more interested in accommodating China's growing influence and interests through cooperation and collaboration.

Second, the "China containment" logic is not in the interests of both sides. Many of US allies have issued their "Indo-Pacific" strategy respectively. ASEAN, Indonesia, France and Germany have all developed alternative models of regional engagement with "inclusion" and "stability." Even the QUAD member India still remains strategically ambiguous toward US' containment intentions. All these countries are aware that China's growing interests deserve to be addressed in line with its expanding influence, and that is not a net-negative outcome for this region.

As for Canada, if it further develops its interests in the Asia-Pacific, it inevitably would do well to consider China's interests because Canada does not stand to benefit strategically from ignoring or against Beijing's perspective on regional events. As Canada is a supposedly independent country, its "Indo-Pacific" strategy is supposed to align with its national interests in this region instead of following US' foreign policy agenda. As stated in the detailed plan "to advance regional peace and security interests", "expanding trade, investment, and supply-chain resilience," "building a sustainable and green future," all these concerns are not confined to the "Indo-Pacific" framework and already have established multiple global partnerships, regional and international institutions targeting at them. None of these partnerships depend on Canada's "Indo-Pacific" alignment with the US, conversely, could be undermined if aligned with what many Asian states view as an anti-China coalition.

Third, Canada's investment in the Asia-Pacific has very limited practical function. As a middle power, Canada's resources on foreign affairs are far from enough for its level of ambition. Even if it claimed to be a Pacific state, the Russia-Ukraine conflict is still the country's top diplomatic priority. With a limited amount of budgetary spending, the Trudeau government has too many domestic agendas to promote, such as feminism, progressive trade, supply chain resilience, etc., which are more of a domestic idealistic mold, and lack understanding and respect to Asia and Pacific countries.

Canada has great ambitions in the Asia-Pacific, however, its asymmetrical capability, misjudgment of regional dynamic reality and aggressive tones toward China have pushed it away from engaging and being accepted by regional states. Its policy that entirely depends on and follows US also harms its interests.

The author is a researcher at Institute of World Economics and Politics, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn