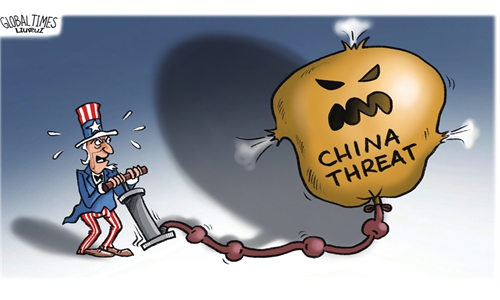

China is not a threat, but a hope for the future of a multipolar world: Spanish journalist

Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

Amid the anti-China propaganda war initiated and led by US and Western political and economic power, foreign journalists find it difficult to break away from the routine of smearing China, said Javier Garcia (Garcia), a former senior journalist in Spain, in an interview with the Global Times (GT). His new book, China: Threat or Hope, was published recently. The book tells about the important things that are taking place in China but are almost unknown to the West. Garcia had worked for Spanish international news agency Agencia EFE for over 20 years. He announced on Twitter that he gave up his journalism career because he was tired of the anti-China propaganda war.

Cover of the book China: Threat or Hope

GT: What made you decide to write this book, China: Threat or Hope?

Garcia: The main reason I decided to write the book was because I thought there were a lot of things about China that were not known in the whole world or in the West overall, for instance the poverty reduction in China, which has been a big effort and represents 75 percent of poverty reduction in the world. But nobody has explained how it was done, or ever talks about it.

I think it's interesting for the world to know; it could be a model for other countries on what they can do to alleviate poverty, which is still a very big problem in the world. And the Western media have frequently criticized China's poverty reduction efforts, but didn't tell us what it was all about. I wanted to tell that story in the book and also to explain China's fight against inequality among the different classes of wealth and what it plans to do in the future.

There has been an amazing transformation in China's thinking about development. In the beginning, it seemed that development was all about development itself, that quantity was only important, and that people didn't care so much about the impact of development on the air, the natural environment, and so on. But in the last decade, the change has been radical. All levels of government and all areas are very concerned about sustainable development and ecological impact. What China calls "ecological civilization" is a really important issue now, and it's something the world should have known about.

In my book, I also explained the "Chinese pragmatism." Many Westerners think that Chinese policy should be very dogmatic. But on the contrary, policy in China is quite flexible and adapts constantly to the problems posed by reality. The Chinese government always tries to essay different solutions through pilot projects to find the best one. This kind of style of governance is very interesting.

GT: What has been the reaction to the publication of your book in Spain and other countries?

Garcia: Some of the views I have expressed on Twitter in relation to China have not been very well received by Western press circles. I even lost friends, which is quite strange. It was actually the first time in my life that I lost friends because of having different opinions. When you speak about China, it is really amazing how people react. Even if I didn't attack anyone, I only express my ideas, the ideas seem to be really sensitive for others. It's quite contradictory to the so-called freedom of expression of the West that you have different opinions but cannot discuss it.

And the book, after its publication in Spain, was well received by the public. It was also one of the bestselling books of its publishing house at the Madrid Book Fair in June. There are many readers who want to learn about China. This is the point, and that was my intention with the book.

GT: In the title of the book, you raised a question, is China a threat or hope? What is your final conclusion to this question? Why?

Garcia: China is not a threat, and China is more a hope for the future of a multipolar world. The image of China as a "threat" is not adequate to the reality of what the country is. The interests of China, its history, the characteristics of its culture and tradition make me think that it is a very peaceful country. China has great peaceful thinkers. All those thinkers who influence most of the Chinese society and culture have been peace lovers, like Laozi, who wrote the classic work of philosophy Tao Te Ching, and Confucius, who advocated harmony, and so on. There were also the voyages of navigator Zheng He, which were for scientific, diplomatic, and cultural explorations. He didn't have the will to colonize or conquer any country. This philosophy of peaceful development has influenced China's foreign policy since the early 1950s.

Given China's history, its traditions, and even its interests, including its own interests in developing trade with the world and its goal of concentrating on improving the living standards of its own people, I do not think that China is interested in subjugating other countries or "exporting" its politics to others. So I don't see China as a threat at all.

Javier Garcia Photo: Courtesy of Garcia

GT: In the last two years, there has been a lot of international discussion about the so-called China's wolf warrior diplomacy. What's your take?

Garcia: I do not agree with the label of "wolf warrior diplomacy." The Chinese diplomats are more assertive than before because China is a big country, but they are not aggressive at all, and they are not "wolves" at all.

China's foreign policy is quite cautious, and as with other aspects of China, it does not like to go to extremes, which is a characteristic of Chinese politics, society and people.

GT: We noticed that you have been to Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and Southwest China's Xizang Autonomous Region, and have also reported in Hong Kong several times in 2019. Why have Xinjiang, Xizang (Tibet) and Hong Kong become favorite targets for the Western media to attack China?

Garcia: They have to find something against China.

First, regarding Xinjiang, we need to acknowledge that political disclosure in China is not completely transparent, which gives some countries the opportunity to release misinformation. It's clear to me that in Xinjiang, there was no ethnic cleansing. There is still a lot that is unclear to me about the education and training centers in Xinjiang, as I do not have enough information, but what I have seen is not ethnic cleansing at all. And the people in Xinjiang live quite well, and this region has developed a lot in the last few years.

With respect to Hong Kong, the demonstrations in 2019 became very violent, and it was necessary to stop that; otherwise, it was not possible to live normally in Hong Kong. Then the central government approved the national security law [for Hong Kong].

Regarding Tibet, many of us in the West had an ideal image of Tibet as a place with mystical monks living in legendary mountains. A kind of dream from ancient times and very poetic. Tibet was like that, but it's amazing how it has developed. You can see that the government has built the infrastructure - roads, bridges, and tunnels. These developments may not fit the poetic and romantic image of Tibet that many people have, but they have lifted the people out of poverty. There are few things more important than helping people live better.

An interesting detail is that in both Tibet and Xinjiang, you can see both simplified Chinese characters and Tibetan words or simplified Chinese characters and Uygur words on the signage of almost every shop. Spain also has other official languages in three historical regions, not just Spanish, but you can't see signs in every shop in the different languages as you can see in Tibet or Xinjiang. In this sense, the minority cultures are respected in China. I don't know what the other journalists have in mind, but as I tried to explain in my book, journalists in the Western media act anti-China because they have to act like that. This is a campaign against China initiated and led by the US and Western political and economic power. The image of China has to be denigrated because it can not represent a model to the developing countries, an alternative to the one imposed by the unipolar world.

GT: What factors do you think reinforce the bias of foreign journalists in China in their reporting on China?

Garcia: If you don't act like a Western journalist as how people expected, you will have no job, no awards, no recognition. The media, the culture, everything pushes you to write negatively about China; the whole system pushes you to be like that. It's very difficult to go away from that because you have very few possibilities to work or to express yourself.

GT: Are you familiar with the Foreign Correspondents' Club of China (FCCC) as an "organization"? What role do you think it plays in the US or Western propaganda war against China?

Garcia: It's not responsible because it's an organization like a group of journalists. However, it is true that it's very difficult to have different views in this kind of club because the English-language media from the US, the UK, and so on make up 70 to 80 percent of the media, and their narrative about China is basically negative.

If the New York Times or the Washington Post publishes something about China, it is difficult for the European media to have their own voice regarding China because they follow the agenda of the American media automatically.

GT: We are against any attacks or unfriendly behavior toward foreign journalists in China. But we have noticed that there is now an antipathy toward foreign journalists in China among many ordinary Chinese people. Can you understand this sentiment? How do you think Chinese society and foreign journalists in China should interact positively?

Garcia: I've never had any problems that I can remember. When I was working as a journalist, I used to interview a lot of Chinese people on the street. Some people would accept to talk and some would say no, but I don't think that was a problem.

It's normal that the people don't want to collaborate because they know that the narrative is not good for China. And that's why they are angry with the foreign reporters, because some foreign journalists do use these people's stories to satisfy their own set narratives, and their narratives are often anti-China, and it's expected that the people don't want to go along with it.