There is a great risk Australia will end up being US' foot soldier in Asia: former policy advisor to Kevin Rudd

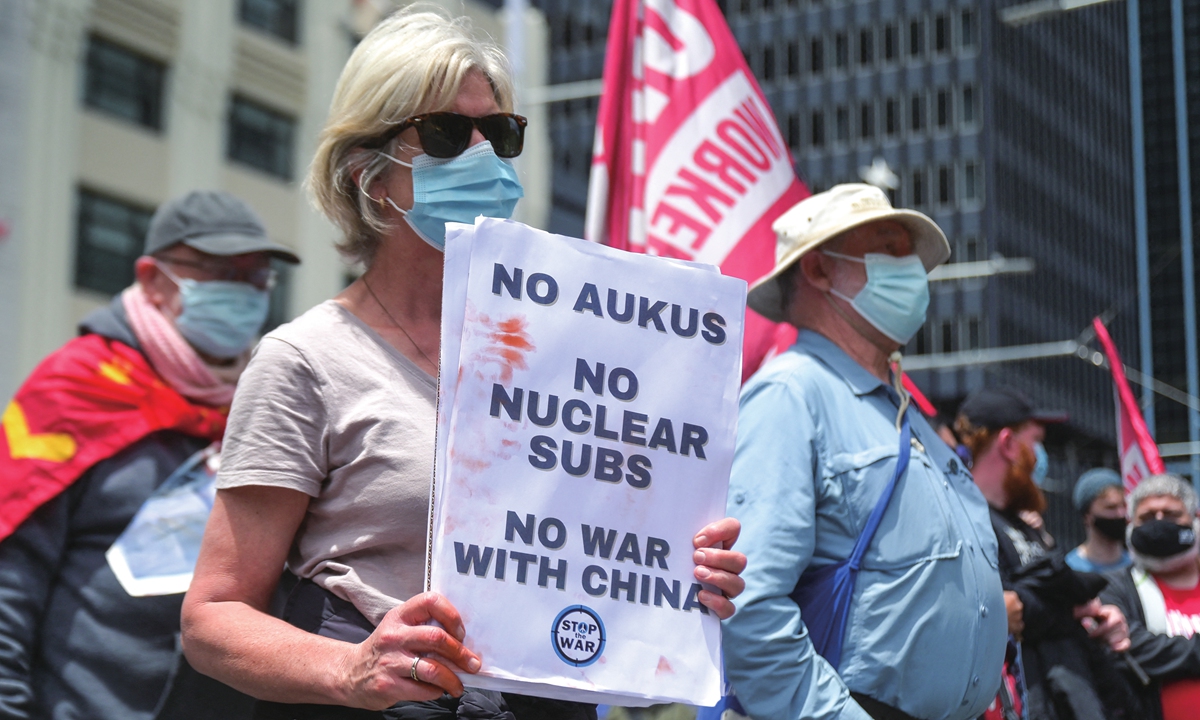

Members of the Sydney Anti-AUKUS Coalition (SAAC) participate in a protest in Sydney, Australia, on December 11, 2021. Photo: AFP

Editor's Note:

Day after day, we hear on the news how the US is accelerating its pace of steering Australia toward becoming a bridgehead against China. On Wednesday, US Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth said Australia could be a testing ground for US hypersonic and other long-range precision weapons under the AUKUS pact. Is this what Australians expected? What concerns do the Australian public share? "Australia needs to think about where it wants to stand in relation to the future of Asia - Does Australia see its future as being part of Asia where its prosperity and security comes from?" Warwick Powell (Powell), chairman at Smart Trade Networks, adjunct Professor at the Queensland University of Technology and former policy advisor to Kevin Rudd, shared his views with Global Times (GT) reporter Li Aixin.

GT: You have raised concerns about Australia accelerating efforts to make missiles for the US on Twitter. Could you elaborate on your concerns?

Powell: There are always a few dimensions to these issues. The growing concern here in Australia is that these recent decisions out of the Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN) meeting effectively consolidate the integration of the Australian defense system into the American defense posture. That means not only practical interoperability, but strategic subordination to the imperatives of the American strategic orientation in Asia.

Part of that group of decisions - missile being manufactured in Australia - raises a number of important questions. Who is going to be the user of these missiles, and against which possible adversaries? As we have increasingly become aware over the last 18 months, as a result of the conflict in Europe, that a military contest, in large part, is a system contest, where a big part of the system is logistics. So, productive capacity close to where you are going to use those missiles and weapons is an important feature of effective system design. This tells us that there is an expectation or planning that these munitions will be used in Asia. That's what they're being manufactured for.

The second concern is the very local one. Munitions factories are legitimate military targets. The question is, where exactly will these munition factories be located? In which cities will they be located? In which industrial precinct and suburbs will they be located? How will they affect the security of the area? And do they make those suburbs a higher military risk than they used to be? These are the emerging concerns around the question of manufacturing missiles here in Australia.

GT: Does mainstream public opinion in Australia share your concerns?

Powell: Public concern is growing. The fact that there is going to be a US base in Darwin and expanded US presence in Darwin came to light by virtue of independent media inquiries, not from announcements made by the government.

There are growing concerns. Firstly, around the AUKUS. And those concerned have crystallized in a significant debate between many former political leaders of Australia and the current crop of parliamentarians. The former prime minister Paul Keating, and other ministers, including former foreign minister Bob Carr, former federal minister Peter Garrett, have raised significant concern about the AUKUS.

More recently, we are starting to see disquiet among sections of the Australian community about not only AUKUS, but the growing militarization of Australia and the absence of war-decision-making reforms that many people are calling for.

At the moment in Australia, prime minister alone has the ability to make the decision about whether or not Australia goes to war. And there are calls from the Australian war reform movement to require parliament to make decisions about going to war. So we are now starting to see these different issues come together.

The broader concerns are about Australian sovereign independence. These questions are not just about the militaristic subordination or integration within the American military system, but also about how the US is treating Australian citizens like Julian Assange.

These issues are blending together in the minds of a growing number of people that have concerns that Australia's sovereign independence has been significantly watered down to a point where independence is no longer a reality.

Warwick Powell Photo: Courtesy Powell

GT: You said in Australia, the prime minister alone can decide whether or not Australia goes to war. Regarding the boosting US-Australia military cooperation, are they preparing for war?

Powell: Whether or not to go to war is a very big decision. Very few countries will explicitly clear that they are getting ready to go to war. What we need to look at are risks and consequences of the decisions that are being made to intensify the militarization of Asia, particularly by the US and its allies in the region.

There has been a common line that says China's military advancements are resulting in an unprecedented buildup in the region. When people say that, they don't tell you that the biggest buildup of military resources in the region has been the expansion of American bases and presence since the WWII.

People forget, that's the baseline reality is that the region is heavily militarized by the American military presence in terms of the bases, intensity and frequency of visits of American warships and bombers.

The second thing to remember is that in terms of China's own military or defense force development, that is basically in line with its GDP growth.

And the third thing to remember is that the American military industrial complex has an annual budget that is greater than the next eight or nine nations' defense budgets combined.

After the WWII, the US actually saw the Pacific at large as America's own domain. They called it America's Lake. So, the American policy regime, regardless of administration, took the Monroe Doctrine and applied it, in effect, to the Pacific. This is where we are today. So if we want to think about whether or not the Americans are preparing for peace by standing behind words like deterrence, we need to bear that in mind.

American scholars have recently concluded that the US is a nation that is "addicted to military intervention." Between 1990 and 2019, the US made 3.7 military interventions per year on average. Between 1946 and 1989, the US made 2.4 military interventions per year on average. The American nation has been the most militaristic nation of all nations, particularly in the post-WWII era. This tells us that there are drivers within the American body politic that make the US reliant on kinetic military intervention as their first and preferred mode of intervening in global affairs. That is why people are genuinely concerned that behind the façade of "deterrence," the US is actually preparing for another military intervention.

GT: Does Australia wish for peace, or does it wish for war, in the region?

Powell: I don't think Australia has the same kind of cultural attachment to military interventions and warfare as the US has. However, Australia does have a history of fighting other people's wars. Some people in Australia are beginning to express forthrightly that Australia is inadvertently being dragged into someone else's war. And because wars can be declared by a single person in Australia without any parliamentary oversight, there is a great risk that Australia will end up being the foot soldier in Asia for the American military strategic rationale. Most Australians that I know don't want to be involved in wars.

GT: Over 20 Australian Labor Party branches around Australia have now passed anti-AUKUS resolutions and the list is growing by the day. Many of the branches are calling on the Albanese government to withdraw from the pact. How do you view this anti-AUKUS push and its prospect?

Powell: At this stage, its prospects of influencing the government are quite low. But time will tell. As I mentioned earlier, with voices like the former prime minister, former foreign minister, and other former Labor ministers, all expressing deep reservations about AUKUS and whether or not it serves the country's interests, let alone the regions interest, I don't think this debate is going to go away easily or quickly.

GT: You suggested we need institutional building to create conditions for lasting peace. Do you have any suggestions for this institutional building?

Powell: We have to start with what there already is - the APEC leaders' forum, which provides a platform for national leaders to address issues of regional interests. We also have important multilateral institutions in Asia that need to feature prominently and centrally in the conversations about how the region's long term security evolves. By that, I mean the ASEAN.

The effectiveness of ASEAN over the years has been underestimated by many, because its style is very low key. It is very much focused on working behind the scene, to achieve consensus among members to progress shared interest. When you are trying to identify and consolidate 10 parties around something, you have to be patient, and you have to be willing to let parties arrive at decisions in their own way and in their own time.

This approach tends not to suit the rhythm that many in the West expect from public policy intervention on the basis that the West, particularly the collective West around the US, has always taken the view - what the West wants, the West gets. It has always had the winner-take-all approach. It has fueled an attitude that the name of the game is about achieving victory rather than a focus on creating a new post-Cold War order of global peace.

The approach that you get from Asian countries is very different. A great example of this is consolidating economic relationships among all of the parties of the region, so that we can start to begin to define common interests of security through mutual prosperity. The RCEP is the cornerstone of that. It was an initiative of ASEAN that was able to bring all of these parties together under one umbrella to create the world's biggest free trade agreement.

Security in the region needs to be built on the basis of an expanding platform of mutual interest. Economic interest is always at the heart of this, because it is through economic interests that mutual benefits arise and enable the parties involved to set aside points of difference while working on things that will improve quality of life of the people in their societies.

American scholar John Mearsheimer once said that push comes to shove, countries will give up prosperity in favor of security. This is a very unfortunate framing of the question. It makes us believe that security and prosperity is an either-or choice, when, in fact, the challenge that we have is to achieve prosperity through security and to consolidate security through mutual prosperity.

GT: Since February, the China-Australia relationship has started to thaw in the economic and trade sectors. How would you comment on the progress of China-Australia ties, in general?

Powell: Clearly, it is recognized that smooth trade between Australia and China is in the interest of both countries, the businesses, the communities and consumers. A thing that's interesting to bear in mind is that even though the diplomatic relationships have not been very good in the last few years, the value of trade between Australia and China today is actually double the value that took place eight years ago. So even though there have been frictions in diplomatic ties, the economic relationships have not seen de-coupling or de-risking. There are a lot of complementarities between the two economies. That's the basis of a successful, mutually beneficial collaboration.

So far so good on the economic front. And hopefully, it will also feed into a couple of more things. One is toning down of the barriers, the unspoken barriers to more cross-country research collaboration, whether it's in the sciences or in other areas of research.

I'd also like to hope that Australia will avoid the spiral that has caught the American body politic in a contest between different parties as to who can appear to be the toughest, the most hardline when it comes to China.

Australia needs to think about where it wants to stand in relation to the future of Asia. Does Australia see its future as being part of Asia where its prosperity and security comes from? Or does Australia predominantly see itself as a country that gained its prosperity and security in Asia, but from outside of Asia? And that question is the contradiction that currently defines Australian public policy in relation to Asia and China.

On the one hand, a foreign affairs perspective is that Asia is already multilateral, that American primacy is over. On the other hand, Australia's military decisions and actions, are all geared to the Americans' desire to reassert supremacy. That's the contradiction. And that's not resolved yet.

GT: You were once policy adviser to Kevin Rudd before he was elected as prime minister, right?

Powell: That was 30 years ago. It was a different time back then when I worked for him.

A national report was written on the role of Asian languages and culture education in Australian schools. It was called the Rudd report. Kevin was the head of the committee and the lead author of the report. It was release in 1994. It recommended to all the governments in Australia - the national government and the state government - every child in Australia, from 9 years old, must learn at least one of four Asian languages, Chinese, Indonesian, Korean and Japanese. The main reason for doing that was it was in Australia's economic interests.

Unfortunately, by 2002, the national government decided to stop funding that strategy and a coherent national strategy on Asian languages and culture education disappeared. What that meant was almost two generations of Australian children have not had a mandatory requirement to develop the skills and the knowledge to work within the fastest growing part of the world and to be able to interact with people from these countries. It's generational. You can't just change that in one day or one year.

That was probably one of the most interesting things that I did when I was working for Kevin. My other job, by the way, includes reading People's Daily and translating for Kevin. That was before the internet and before AI translation. China was a big part of his personal and professional life, but in general he was interested in the region.

The greatest challenge the world faces is whether or not a different set of forces to the neocons will gain primacy. As long as the neocons dominate the American body politic, the US will continue to try to impose a winner-takes-all mentality and strategy on the world.

The danger for America is that by doing that, it will progressively isolate itself as the rest of the world continues to build a different set of institutions, whether it's BRICS, whether it's new payment platforms, whether it's new trading agreements. As America inadvertently isolates itself and drags Western Europe with it, it gets angrier. That's the risk.

The fundamental issue is whether or not the neocons can be brought to heel, can be defeated or taken control of on the one hand, and on the other hand, is how patient everyone else in the world can be while they are continually being provoked by the neocons.

If the rest of the world can be patient and focus on finding common ground, building new institutions, finding new pathways to collaborate, whether it's dedollarization, collaborative projects, while the neocons and America's own domestic problems sort themselves out, then I think we can come out at the other end with something quite different. So at the moment, the risk is an American body politic that is struggling to cope with the idea that what it thought was a victory, was nothing of the sort.