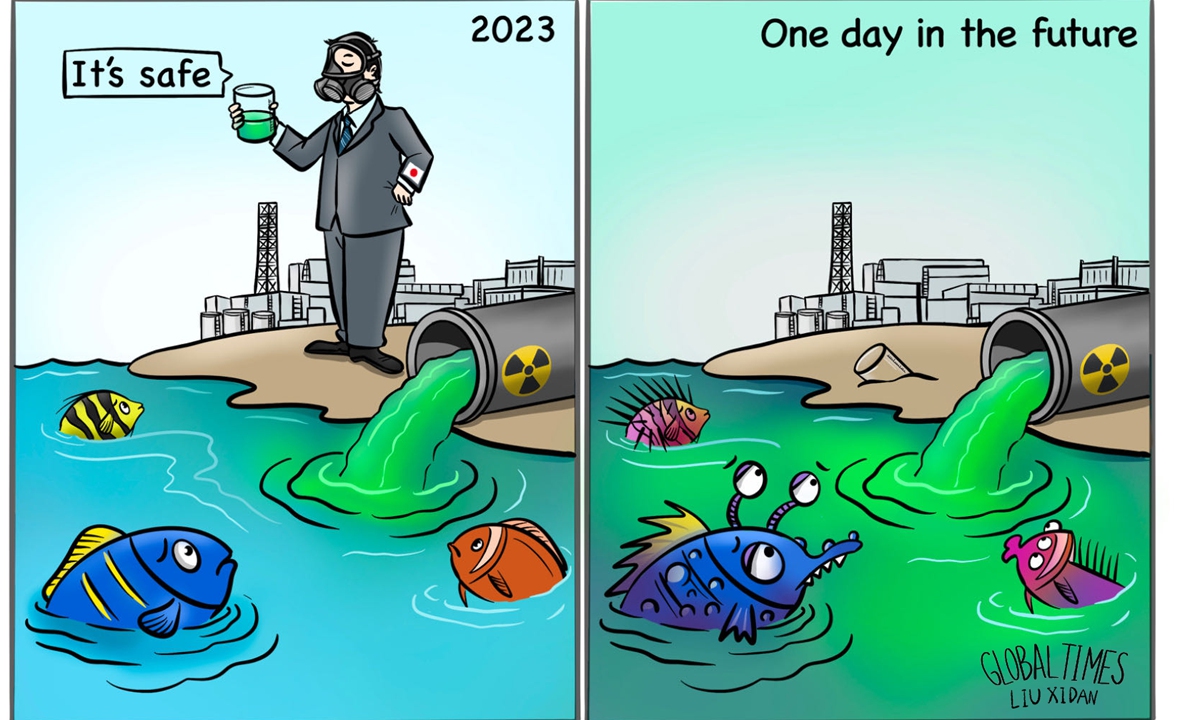

llustration: Liu Xidan/Global Times

Sometime this year - possibly later this month - Japan will start dumping nuclear-contaminated wastewater from the doomed Fukushima Daiichi power plant into the ocean, with plans to continue doing so for the next 30 years.Waves from the ocean also break onto the shores of many other countries, which are naturally concerned about the polluting effects on the sea and marine life. However, such concerns have been dismissed by Tokyo.

Japanese media have parroted their government's line that the controversial disposal of more than a million cubic meters of toxic waste will have little effect on the environment. This is a continuation of the "safety myth" which led the authorities to declare years ago that the plant itself was completely safe. Safe, that is, before the tsunami struck.

Some scientists in the UK say the dumping cannot be declared risk-free and that more research needs to be done. In fact, Britain may be uniquely qualified to warn Japan's politicians of the danger of their plans, because in the Irish Sea, a stretch of water off the UK's northwestern coast, it has probably created the most radioactively polluted marine environment on the planet. The cause? Decades of discharging contaminated water from the country's infamous Sellafield nuclear site into the open sea via an about 3 kilometers pipeline. This gives the issues around the proposed dumping by Japan a horribly familiar feeling in the UK.

In the UK, it has been said that the Irish Sea, which separates the British mainland from the island of Ireland, is considered the most contaminated sea in the world. This is blamed on the vast nuclear facility, located in Cumbria, on the west coast of England. This facility was the starting point for Britain's atomic bomb program in the 1950s, was the site of the world's first nuclear power station, and is now also home to some of the most hazardous buildings in Europe. It is currently the site of a mammoth reprocessing and decommissioning project.

It is from this site that, at one time, up to two million gallons of radioactive water was discharged into open waters every day. It was thought at the time that the sea would safely dilute the plutonium, caesium-137 and iodine-129. Levels of radioactivity allowed during the time of peak dumping, in the 1970s, were about 100 times what is deemed to be safe today, because that's what the experts at the time considered safe. History has proven them wrong - and according to some researchers, contamination from Sellafield is now detectable in the Arctic Ocean and the waters of northern Canada. One alarming study found that plutonium particles, washed onto Cumbrian beaches, were blown by the wind up to 37 miles inland.

This is a history lesson that the Japanese might do well to learn from. Scientists today have learned a lot of knowledge and are now better informed, confidently predicting what they believe to be safe. So did the scientists at Sellafield all those years ago. When Fukushima was built, the authorities repeatedly assured the world that it was safe. Obviously, a tsunami proved them wrong.

There has been understandable opposition to the controversial plan from Pacific governments, including - among others - China, Australia, New Zealand and numerous smaller island countries. There are serious concerns about the accumulation of radioactive particles, the uptake by marine species and the potential for it to travel up the food chain. Hong Kong has already warned that Japanese seafood imports would have to be banned if the dumping proceeds.

Their doubts and objections are not born of only self-interest but are shared beyond the Pacific, even to the other side of the world. In the UK, journalists for the New Scientist journal have amassed testimony from leading experts questioning the assessments of safety arising from the proposed dumping. The article warns that although the contaminated water being stored in 1,000 tanks has been treated to remove 62 radioactive toxins, it has not been possible to remove tritium, an isotope of hydrogen. Awadhesh Jha, a researcher at the UK's University of Plymouth, has called for an international research program into the impact of this. Ken Buesseler of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts expresses concern about the potential accumulation of hazardous substances such as ruthenium-106, cobalt-60, and strontium-90 on the ocean floor. He emphasizes that these contaminants are even more likely to build up on the sea floor, with an increased risk of entering the food chain.

It may seem facile to appear wise in retrospect, but it is far better than to be remorseful in retrospect. By the time Sellafield's experts were proven wrong, it was too late. It is not too late for Fukushima, if only they will listen. They should learn from history.

The author is a lecturer and journalist living in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn