Who is trumpeting subservience to US, frowning upon rejection to US-led Red Sea taskforce in Australia?

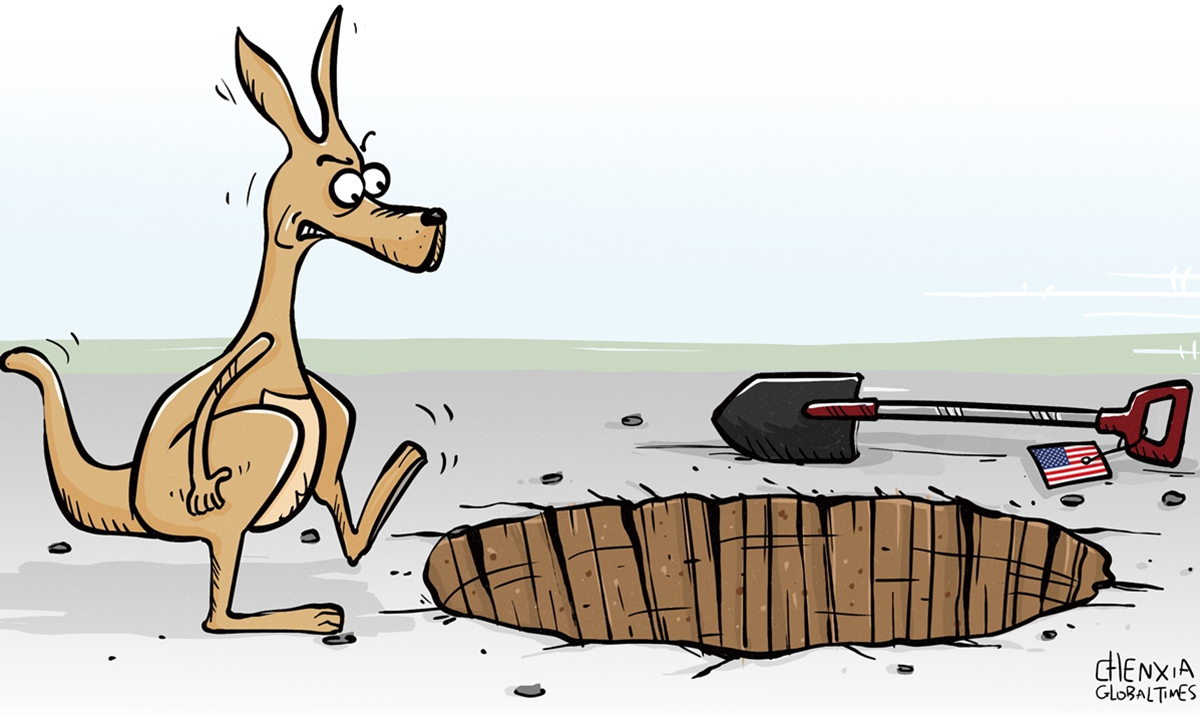

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

The Australian politician and diplomat, Herbert Vere Evatt, played a critical role in the founding of the United Nations, serving between 1948 and 1949 as President of the UN's General Assembly. Evatt had his unique outlook at and principles about Australia's international standing and diplomacy, which have been influencing generations of Australian foreign policymakers. One of Evatt's most influential arguments is that Australia, as a global citizen, has its own independent role in international affairs, in particular for the maintenance of peace and stability of the region it is geographically located, i.e. the Asia-Pacific. He pointed out that Australia's relations with Britain and the US are important, but Australia also needs to develop its own position on global affairs.Discussions and studies of contemporary Australian diplomacy never fail to mention the fact that Australia had participated in every major military operation that the US launched in various parts of the world since the end of the World War II. It seems that Australia had always been acquiescent to comply with Washington's global and regional strategies to join its various military adventures, which had in fact divested Canberra of its independence in making its own international geostrategic decisions and policies.

It is therefore a significant move that the Albanese government prudently rejected a recent request by Washington to join its naval operation in the Red Sea. There is a recognizable echo to Evatt's philosophy when Australia's Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Richard Marles said that "We need to be really clear around our strategic focus and our strategic focus is our region."

Australia is an Asia-Pacific country, and Australia's economic development and political influence have grown in synergy with the development of this region in the recent decades. In 1992, former Australian prime minister Paul Keating famously said in his speech, Australia and Asia: Knowing Who We Are, that "Asia is where our (Australia's) future substantially lies …we can and must go there… [and] this course we are on is irreversible."

Therefore, Australia is naturally justified to identify its immediate region as the most strategically important to its national interest. What's more, it is common sense that Australia, as an independent sovereign nation, makes its decisions at its own discretion.

A sovereign nation can be a member of multilateral or bilateral alliances or partnerships. But such coalition arrangement should not override or deprive of its right of self-determination.

To position itself as the US' "deputy sheriff" only betrays a servitude mentality which eventually diminishes Australia's international standing as a significant middle power. Strategies and policies obviously need to be formed based on assessments and evaluations of the geostrategic context and domestic circumstances to reflect and serve Australia's own national interest.

In an interview with the far-right media outlet, Sky News, former Liberal foreign minister Alexander Downer lamented that Australia is being made into a "second-class ally" of the US. Apparently in some of the Australian minds, Australia should indubitably be among the first echelon of Washington's allies. It should be out of the question that Australia could have reservations or even rebuffed a US request to act as a chess piece on its global chessboard, no matter how remotely it would be cast by Washington.

The famous Australian writer A. A. Phillips once called such subservience among the Australians at his time in the early 1950s as the "Cultural Cringe" syndrome. A typical Australian intellectual with such psychological diffidence would from time to time have qualms and scepticism about the merits of the Australian culture - he "hedges and hesitates, asking himself 'Yes, but what would a cultivated Englishman think of this?'"

Likewise, some Australian political thinkers today seem to have set Australia's position on the ladder of US' allies as the paradigm to judge the soundness of the national policy. According to them, Washington should not be challenged or annoyed, and its demands not to be upset or even defied, so as to avoid isolating Australia among the US' allies. Such a mindset is a political cringe which would only be crippling to the further outreach of Australia's role as a significant and positive global actor.

It is therefore highly advisable for those Australian political elites to return to Evatt and Phillips, to reflect upon and learn from their wisdom. Mature nationhood comes with "a relaxed erectness of carriage," instead of nervously making calculations about Australia's rank on the US circle of friends.

The author is a professor of Australian Studies at the East China Normal University in Shanghai.opinion@globaltimes.com.cn