People calling for slavery reparations protest outside the entrance of the British High Commission during the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in Kingston, Jamaica on March 22, 2022. Photo: AFP

Editor's Note:

From the 15th to the 19th century, the transatlantic slave trade of colonial countries brought great disasters to the people of Africa and the Caribbean. Over the centuries, the struggles to seek justice have never ended. In her I-Talk show, Global Times (GT) reporter Wang Wenwen talked to two activists from the Caribbean island nations of Barbados and Jamaica - David Denny (Denny) from Barbados is the general secretary for the Caribbean Movement for Peace and Integration and Verene Shepherd (Shepherd) is a member of the National Council on Reparation (Jamaica) and a vice-chair of the UN's Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination - about their endeavors to seek apologies and reparations from European countries.

GT: Can you tell me about your involvement in the reparation campaign?

Denny: I was a member of the anti-apartheid movement in Barbados for many years. It went back to 1977 in the South Africa liberation committee, the Free Nelson Mandela committee, and the Pan-African movement of Barbados. As a founding member, I served as general secretary of the Pan-African movement of Barbados at the time. Coming out of the Pan-African movement in the 1980s, we felt a need and a call for us to work toward fighting a battle for reparation, because we felt that reparation is something that should be paid to persons who were taken advantage of by Western Europe, in particular here in Barbados by the royal family, and the rich and wealthy people from England. For me, as a young man at the time, I saw the urge and the need to be part of a process that was prepared to fight for reparation. It was a very tough battle in the 1980s, because white people looked at us as mad men and women.

But now you can see that there are some changes happening now, because of the work that we did in the 1980s and 90s in relation to the reparation battle. Conditions for full recognition have been created, for our position as it relates to reparation.

I am happy because I have been part of a movement that helped to fight a very serious battle against US imperialism, against British colonial powers, and even against our local capitalist system that have exploited our people. So I am very happy to know that I spent my life as part of a team, fighting many battles to create the conditions for our poor and powerless people in Barbados and in the Caribbean.

Shepherd: Ever since I began to study history at high school, coming through various universities, I have been conscious of the need to join those who were calling out for compensation, for historic wrongs, because you can't study history and not be aware of the historic wrongs.

Once you have studied history and you are aware of the historic wrongs, then the next step is to join the campaign for reparatory justice. But in terms of a formal joining of the campaign, I would say that came around 2001 out of the Durban anti-racism conference. Those who were at the conference when they came back to Jamaica, I can think of Barbara Blake Hannah. She started the Jamaica Reparations Movement, and she asked me to be the consultant.

Officially, since 2001, I have been in the movement. In the 2000s I also chaired the Jamaica National Reparation Commission. I'm now vice chair of the CARICOM Reparations Commission.

GT: During your campaign, did you experience any pressure or hardships?

Denny: There have been some very serious hardships. In the 1980s, because of our ideas, some of us were denied the opportunity to employment. Some of us were monitored by the police force when we traveled and when we moved around in Barbados. To make the call for reparation, to make the call against the apartheid system in South Africa, to make the call against imperialism, we were seen as a revolutionary, and we were seen as someone against the system.

Therefore, the system to the private sector agency and the state agencies did everything possible to oppress men and women who shared our views and who were prepared to fight for changes that we are now enjoying today.

Shepherd: By 2001, when I got officially involved in the movement, there was widespread support within the CARICOM region and in the UK, in the Netherlands and elsewhere, about the rightness of our struggle.

But there was some pushback from the elites, not from grassroots people, but from the elite, those who consider reparation as begging. But it's not an act of begging. It's a right for a crime against humanity. But I think that gradually, more people from even that group have come on board. And now, I think it's a galloping 21st-century movement.

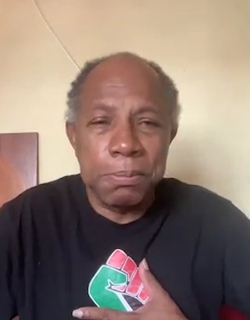

David Denny. Photo: interview screenshot

GT: Why is it so difficult for African and Caribbean countries to seek reparations from Europe?Denny: When you look back at slavery, black people were treated the worst and seen by white rich people as second-class citizens. They do not believe that we are entitled to reparations. For instance, we have a plantation in Barbados called the Drax Hall plantation. This plantation today is owned by Richard Drax. Richard Drax is considered to be the richest parliamentarian in the UK parliament. At this present moment in Barbados, Richard Drax is still making profits from that plantation. And black working-class people are still being exploited on that very plantation right here in Barbados.

Western countries will say, "We are sorry for the exploitation that took place during slavery." Then they will say that it was there, and it was not them. And they were trying to ease themselves out of the situation by not paying reparation to African people who have suffered from slavery. But we know that if you look at England, the English economy survived and benefited from the exploitation of slaves. If you get an opportunity to visit Liverpool, there is a slave museum that tells you that story.

Shepherd: With the exception of the Netherlands and Belgium who have actually used the word "apology," most others have slid around the demand by using regrets. "We regret. If it was now, it would be a crime. But it was legal at the time. We can't pay current generations. I'm not responsible for a historic wrong." So those are the arguments that we hear, but we continue to press, because those are not legitimate arguments. From what I gather from my legal colleagues, there is nothing in international law which prevents the descendants of those who are affected by the original crime from claiming reparation.

GT: Germany recently expressed shame for its colonial atrocities. Last year, the Netherlands offered a formal apology. But the UK is yet to do so. What do you think of the UK's attitude? Do you think the UK will ever pay back and make an apology?

Denny: I went to the UK early this year. When I arrived in the UK, the very first place that I went to, and the very first protest action that I participated in, was outside of Richard Drax's gate in the UK. I felt sad and hurt.

I endured a lot of pain because Richard Drax has the longest yard wall in the UK. Richard Drax lives on the largest estate in the UK and the Drax family has the most estates in the UK. All of that came about because Richard Drax and the Drax family, James Drax to be exact, who was the head of the Richard Drax family during that period, were allowed to exploit our African people in Barbados.

The exploitation of our African people in Barbados is what created the conditions and the finances for the Drax family to build that kind of estate or to own that kind of property in the UK. I had the opportunity of visiting several places in the UK. I visited Manchester, Liverpool, and what I found in the UK was that a lot of working-class people in the UK are in support of the call for reparation. And that means a lot to me and the reparation struggle because we have some allies. The money that was created by that elite class in the UK was also used to exploit the British working class that are mainly white people so that they also have a fight on their hands with the elite class in the UK. And because of that, they have extended this solidarity with us in the Caribbean in relation to the call for reparation.

I am hoping that early in the New Year I can go even further. That is, I will visit the UK and then other Western European nations, so that we can address them and make the call for reparations.

Shepherd: Everyone is pushing on all fronts. The demand, and the campaign, is not just from those who were harmed in the Caribbean or the descendants. There's a push now from Africa. There are groups in the United States, Europe, Latin America and the UK itself. As the movement grows, I hope that the UK will realize that it does have this responsibility.

You do have individuals in the UK who are coming forward. They have formed a group called the Heirs of Slavery. Laura Trevelyan, who was a BBC journalist, resigned from her job. She and others have come forward to join the movement and help the Caribbean to lobby the states. And they themselves are trying to see what they can do financially for the region. I think that is good. But the major responsibility is a state. The state provided the environment and the laws within which the ancestors of these individuals could participate in the trafficking and in chattel enslavement.

In any event, we continue to suffer from the legacies of that crime. So it's still on the table. The demand is on the table and it is legitimate. We will just have to force them to come to the table. The Caribbean has actually written to these European countries asking for a meeting. So far that meeting hasn't taken place and a second round of letters is being drafted, so we will see where it ends up. But the pressure is still on.

Verene Shepherd. Photo: interview screenshot

GT: Recently, African and Caribbean countries partnered to form a united front to seek reparations from European countries. Are you optimistic about it?Denny: I am happy about that because it says that we have opened up the eyes of our African leaders. We have opened up the eyes of our Caribbean leaders so that they can unite themselves together to help us fight this reparation battle. The reparation battle must be fought at different levels, at the governmental level, and also at the civil society level. I think we also need to take it to a trade union level so that working-class people can unite together internationally, whether white or black, to demand reparation for our people.

Shepherd: I'm very optimistic because we have long been saying to the continent of Africa, "You have to come on board. You have to join us." In 2001 at the anti-racism conference in Durban, South Africa, that did not happen. The CARICOM region was left on its own.

I didn't go, but from my understanding of the reports, African nations chose bilateralism rather than a communal interest with the Caribbean. So the recent conference in Ghana ended in a very hopeful manner for the Caribbean. We hope the movement will grow because once Africa comes on board, I think greater success will be achieved. And in any case, they are making demands concerning their cultural heritage. We see Bennett bronze is being returned. So the reparation movement is also in Africa and now we are cementing a better relationship.

GT: The idea of seeking reparations went largely unnoticed in Europe and the US some 20 years ago. However, now, the issue is routinely discussed and constantly seen in the media. How do you analyze the trend? Does the movement have anything to do with the rise of the Global South on the world stage?

Denny: As I mentioned earlier, in the 1980s we were seen as mad people. People didn't believe that we would reach this level. But because of the conscious building among our people, we have been able to force governments in the region to recognize our call. It took some time, but we were able to create the conditions for conscious building.

And I'm also happy that I am witnessing what is taking place in the world, and that our work and our solidarity and togetherness are benefiting. And we can see the fruits of our work. I'm happy to know we have achieved some of our goals and objectives and we have been able to build that level of consciousness that has created the respect that we wanted from this battle for reparation.

Shepherd: 20 years ago, maybe 30 years ago, only a few people were talking about reparation, but now there is a flood of support. As the campaign grows, it is going to be harder for people to ignore. But I have to say, though, that we shouldn't date the reparation movement to 30 years ago because I interpret the activism of enslaved Africans as demanding reparatory justice. They may not have used the term, but there were protests, nonviolent and violent. All of that was geared toward ending chattel enslavement. And in the post-COVID period they continued to lobby and fight and protest for justice. So we are just carrying on a long struggle and bringing greater attention to it and coaching it within the language of reparatory justice. There has been a long movement, including the Rastafari, (religious and political movement, begun in Jamaica in the 1930s and adopted by many groups around the globe, that combines Protestant Christianity, mysticism, and a pan-African political consciousness,) calling for repatriation to Africa, because we are stolen people. We have the right of return of our cultural heritage. If you look all that, you'll see that this is just the more recent dimension of this long struggle.

The Global North is also joining the movement, with migration and with the realization from those who are settled in the North that they are not respected as equals with those citizens of the North. I think the injustice that people have experienced, the racial profiling, this whole scandal with the Windrush generation in the UK, (the generation of Commonwealth citizens who came to live in Britain between 1948 and 1971,) the realization that there is no true equality and racial discrimination is alive. All of that means that the movement is now a joined-up one with North and South, East and West. Therefore, the movement can only continue to grow and succeed.