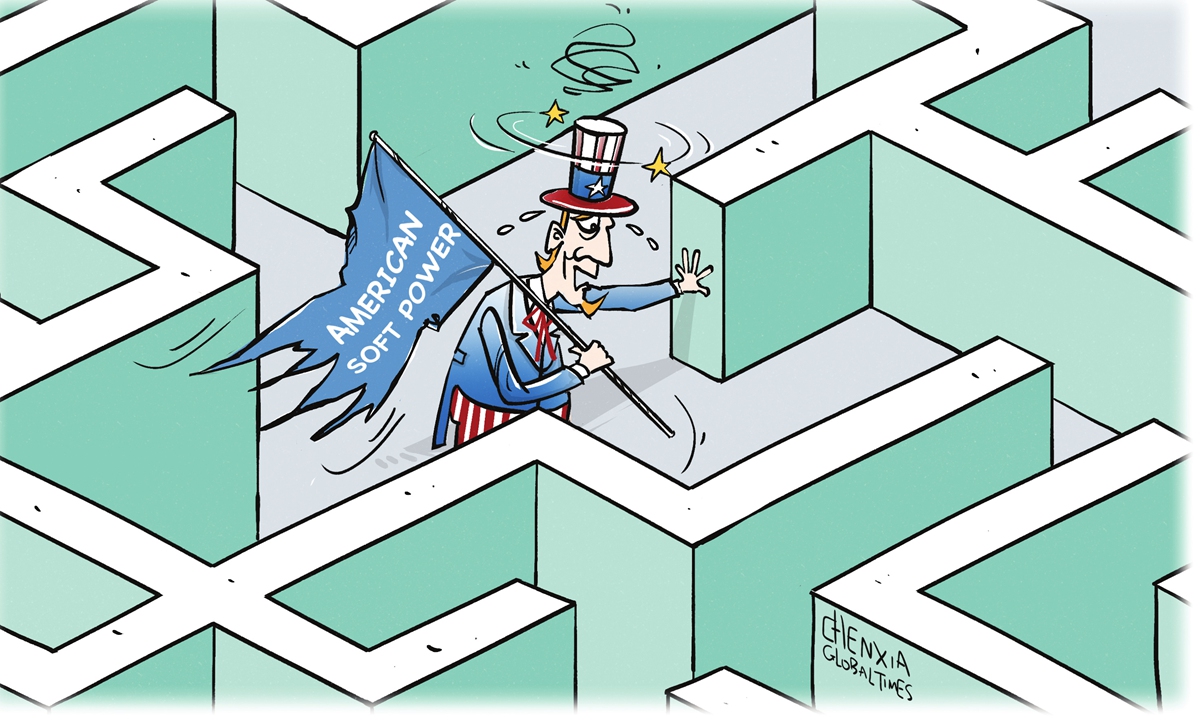

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, the US was the undisputed hegemon. Able - and willing - to use its military might in places near and far (albeit not always with success), the US basically told the world to get in line.

At the same time, the US benefited from its ability to promote a kinder, softer and more positive image here, there and everywhere. Through its many professional sports teams, entertainers, artists and others who traveled the globe on "goodwill tours," the US used so-called soft power to convince global audiences that it was a force for good. Along the same lines, the US defined the rules by which organizations such as the International Monetary Fund operated. The US did not dictate how these agencies ran, but it certainly was most instrumental in deciding what they did.

Therefore, it was no surprise that many political scientists and other experts believed that in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the West, with the US driving the bus, would be unchallenged in its dominance for decades to come. In such an environment, if the US continued to win hearts and minds - a primary goal of soft power - then it was positioned to remain in its hegemonic position. It seemed so simple.

Suffice it to say, that did not happen. And no one should expect that it will. In fact, a case can be made that the US and its allies won the Cold War and then somehow lost the future.

How did American soft power also lose its way over the past decades? A complete answer cannot be delivered here, in just a few words. When the history of this century is written, two events might come to explain how the US went off the rails.

The first is the horrible events of September 11, 2001. Manipulating the justified anger that millions of Americans felt, the White House turned a mission of revenge into a democratic crusade. Retaliating against al-Qaeda was not enough. The goal was to transform multiple countries in the Middle East into functioning democracies. That objective was never even close to being realized. In fact, it had the adverse effect of giving a modern-day example to critics who had been saying for years that the US was hell-bent on military excursions that it simply expected to win. Put another way, the country wasted the goodwill that was offered by nations big and small following that tragic September day and also forgot the necessity of injecting soft power into whatever it did, and the world noticed.

The second is the election of Donald Trump in November 2016. His predecessor had improved the US' standing around the world largely because he was open to suggestions that the US' past was not "great." Trump trampled on all of that. Building on the outrage that certain "news" organizations created between 2009 and 2016, the right's anger dominated news discourse with claims that terrorists were invading the country on a daily basis and certain countries were determined to destroy the US' place at the top of the economic pyramid. Trump told anyone who would listen that the US would take lessons from no other nation on how to conduct its affairs. He told countries all across the globe to either support Trump's vision to "make America great again" or they'd risk economic and other penalties.

In this environment, no sensible person would buy the idea that a sports team or an artistic exhibition could sway the growing perception that the US was no longer the beacon of freedom and peace that it had claimed to be for decades. A further argument could be made that Trump simply did not care about soft power.

As a result of these two events, the most corrosive elements of nationalism developed within the US. Enemies, within the country and abroad, had to be found. Allies were either all in with the country's ambitions or not. Hard power became the only power.

Joseph Nye, currently an emeritus professor at Harvard University, is perhaps the world's foremost authority on soft power. His recent book, Soft Power and Great-Power Competition, examines how the US and other nations, including China, might use soft power in the 21st century. He warns that while "the US still has leverage over particular countries, it has far less leverage over the system as a whole." One reason is the "recovery of Asia" to its place in the global system of power. Nye warns that "whose story wins" is perhaps more vital now than ever before.

If Nye is correct, and the depth of his academic research affirms that he knows what he is talking about, then the US' "story" right now is one filled with anger and rage, hostility and hatred.

Recently, an editorial in The Hill came close to begging US leaders to again use its athletic, creative and similar communities to spread a kind of gospel that the US is a place of virtue and its values should be endorsed across the globe. Why would any international audience accept such a message right now?

The author is an associate professor at the Department of Communication and Organizational Leadership at Robert Morris University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn