Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

When a story appeared on the front page of one of Britain's most established newspapers accusing China, Russia and Iran of working to destabilize the UK by undermining confidence in its constitutional monarchy by using social media to troll the wife of the heir to the British throne, readers could be forgiven for thinking it was a joke. How could anything so absurd, so risible, be taken seriously? Sadly, it was not a joke. There it was, the "splash" in the Daily Telegraph, one of the UK's right-wing newspapers, claiming that the three bogeymen of Western geopolitical thought had targeted Kate, the Princess of Wales, the wife of Prince William, heir to the reigning King Charles III.They were accused of helping to fuel wild conspiracy theories about the princess's absence from public life for a prolonged period. It is now known that her non-appearance at official events was due to poor health, including a diagnosis of cancer. Before this was made public, social media conspiracists were promoting lies and rumors about her supposed "disappearance". Even after the truth emerged, the online antagonists kept up their grim work.

Then on Monday the Telegraph story appeared, addressing the issue of conspiracy theories and disinformation, with a story which itself was loaded with conspiracy theory and disinformation.

The "facts" supporting its allegations against China, Russia and Iran seemed thin. The allegations were substantiated by anonymous government or Whitehall "sources" who gave anodyne, imprecise comments which could have been used in almost any story about social media abuse. Nowhere did the "sources" categorically name China, Russia or Iran - or specify any hostile state actors outside of the UK actually participating in the hysterical online rumor mill surrounding the princess. On close examination, the reliability of the story dissipates like mist in the morning sun.

Ironically, the Telegraph's government source warned that state adversaries work to "destabilise things - whether that is undermining the legitimacy of our elections or other institutions". It is widely believed that before the year is out, Britain will have gone to the polls in a general election, and the integrity of the voting process and public confidence will be very telling of the electorate's faith in the system.

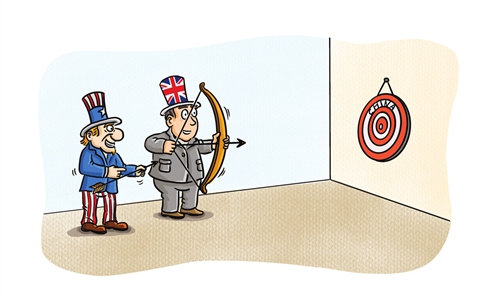

But that faith, that critical public confidence, is currently already at an all time low. The UK's Office for National Statistics recently found that the British public's trust of its political parties stood at just 12 percent, of the government at just 27 percent, and of parliament at just 24 percent. At times like this, it is very convenient for politicians to be able to boost their own credibility by pointing to alleged outside threats as a useful distraction. For them, China, Russia and Iran slip into these roles as easily as a hand into a glove, and stories such as the Telegraph's play into that narrative.

It was no accident that the story alleging an outside state attack on the Princess of Wales came on the morning of a major announcement by the British government which was almost designed to appeal to domestic China hawks. Deputy Prime Minister Oliver Dowden told the House of Commons that China had waged "malicious" cyber campaigns against members of parliament and the Electoral Commission, the UK's voting watchdog. To counter these campaigns, he said that sanctions would be placed against two individuals and a company deemed responsible. Some of the data allegedly stolen contained the names and addresses of more than 40 million voters - yet these are accessible to almost anyone in publicly available documents.

Dowden was certain of China's involvement: "The cyber threat posed by China-affiliated actors is real and it is serious."

However, a simultaneous statement issued by Britain's National Cyber Security Centre, a division of the UK's GCHQ eavesdropping and snooping organization, said only that China was "almost certainly" responsible, stopping short of unequivocally apportioning blame. It also pointed out that the alleged interception of MPs' emails occurred three years ago. Perhaps it is only another coincidence that the allegations are becoming public only now, and the government's response gives the impression of being tough on a potential adversary, in an election year.

There is a pattern of negative media reporting about China which directly affects public perceptions and in turn helps shape the British state's foreign policy positions. In recent weeks, there have been many examples of distorted, disingenuous and hypocritical coverage of China.

Recent research at King's College, London, shows this type of media behavior reinforces and contributes to extensive negative views about China, resulting in more hawkish policies toward China - something which is "in line with the interests of lobbyists and politicians inside and outside government who favor that approach".

Stories like this appearing in the Telegraph are part of the process, and while they appear superficially shocking - and on examination perhaps comical - they form part of a tapestry of propaganda which moulds public perceptions and attitudes which may well suit the politicians that seek power, but which serves the citizenry poorly. It's called propaganda.

The author is a journalist and lecturer in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn