Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

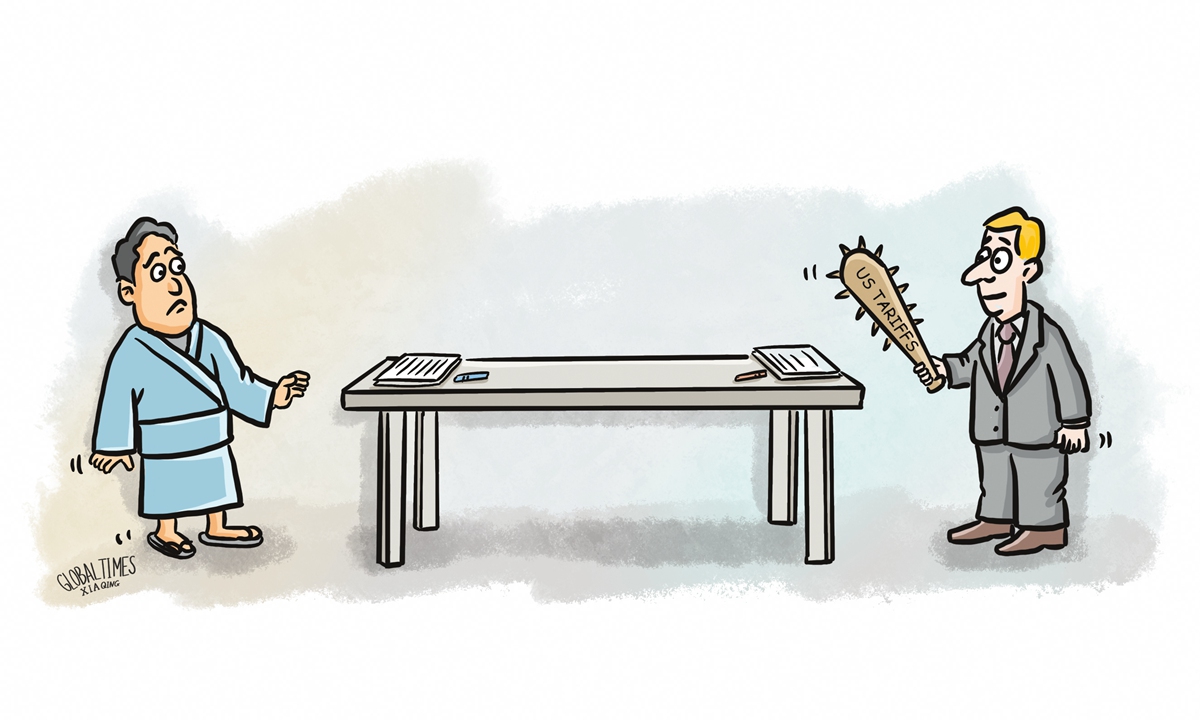

On Thursday, Japan's Economic Revitalization Minister Ryosei Akazawa will meet with the US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent for the second round of US-Japan tariff negotiations. The US side seems determined to secure an agreement quickly in order to offer other countries a "template," but there is widespread pessimism in Japan about the talks' prospects. According to the latest Nikkei survey, only 22 percent of respondents believe the US-Japan tariff negotiations will yield results, while 70 percent think they won't.

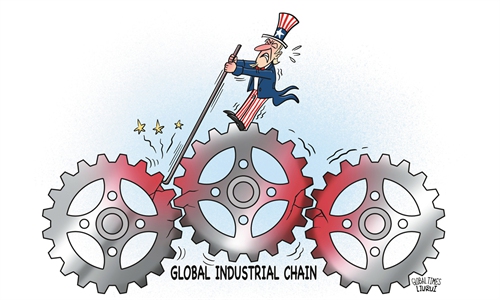

This divergence in US and Japanese attitudes stems from the US' "sky-high demands." In the first round of talks in April, the US did not hold back in presenting three major demands to Japan: the removal of US-facing tariff barriers, the elimination of the US-Japan trade deficit and an increase in Japan's financial burden for hosting US forces. Due to the wide gap between the two sides, the first round yielded no substantive results. Facing domestic pressure, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba emphasized that Japan will not make compromises for the purpose of quickly concluding upcoming tariff negotiations, even going so far as to warn that US tariff policy "has the potential to disrupt the global economic order" - a highly unusual show of firmness toward the US.

In recent years, Japan-US relations experienced a "honeymoon" period, with Japan playing a significant role in America's global alliance system. Although Japan was somewhat prepared for the arrival of the "Trump shock," it continued to believe that, as a "close ally," it should receive special treatment.

In February, during Ishiba's visit to the US, the two countries announced the pursuit of a "new golden era" in their ties, which relieved domestic concerns in Japan. But following this, the US not only criticized the security treaty with Japan as nonreciprocal and demanded Japan increase defense spending, but it also repeatedly criticized the "imbalance" in US-Japan trade. Subsequently, the US announced tariffs on steel, aluminum and automobiles, as well as a 24 percent "reciprocal" tariff, breaking the last bit of "fantasy" Japan had about the US administration. In a parliamentary speech, Ishiba even used the term "national crisis" to describe Japan's predicament.

In 2024, the US remained Japan's largest export market, with Japan recording a trade surplus of $68.5 billion with the US. Automobiles were a significant contributor to this surplus, accounting for approximately 30 percent of Japan's total exports to the US. By targeting Japan's auto industry with tariffs, the US strikes at the country's economic linchpin. If a 25 percent tariff is imposed, Japanese cars will lose their competitiveness in the US market, which will then ripple through Japan's domestic supply chains, severely undermining the foundation of its manufacturing sector. Moreover, if Japanese automakers further shift their production lines to the US, it could accelerate the hollowing out of Japan's domestic industries. More dangerously, the US' ever-changing tariff policy will force Japan to navigate an unpredictably external trade environment for the next four years, making mid- to long-term investment planning impossible. And with fiscal resources stretched thin, Tokyo will face fierce resistance to any substantial increases in defense spending or contributions to the cost of US forces stationed in Japan. Most Japanese believe they cannot openly "confront" the US as China might - being heavily dependent on American security guarantees and export demand - but neither can they concede unconditionally.

Faced with US pressure, Japan's primary concern is the potential recurrence of the Plaza Accord. In the 1980s, at the peak of Japan's economic strength, the US used the Plaza Accord to force a significant appreciation of the Japanese yen. This move contributed to the bursting of Japan's economic bubble and ushered in what became known as the "lost decade." After a prolonged economic slump, Japan's economy has recently shown signs of recovery, only to face renewed strong pressure from the US. Today, Japan no longer possesses the leverage to "buy America" as it once did. Confronted with the US' steep demands, Japan finds itself with limited bargaining chips.

While the Plaza Accord of the 1980s may be difficult to replicate, Ishiba's characterization of a "national crisis" is far from alarmist. For Japan, shifting strategically from crisis management to seizing opportunities may be more crucial than merely concluding a tariff agreement. Japan should strive to regain strategic autonomy and economic independence amid the global restructuring of the economic and trade order.

The author is a distinguished research fellow at the Department for Asia-Pacific Studies of the China Institute of International Studies. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn