US compounds its mistake with plan to revoke waivers for foreign chipmakers in China

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

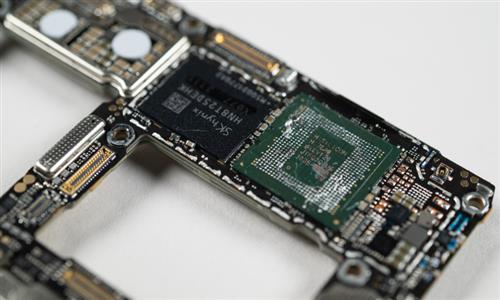

Recent media reports indicate that the export control division of the US Commerce Department had notified major semiconductor manufacturers, including Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix, of its intention to revoke waivers they have used to access American technology in China, including canceling their waivers for shipping US chipmaking equipment to their factories in the Chinese mainland.While this does not amount to a ban on chipmakers operating in China, it is expected to create significant difficulties in areas such as equipment upgrades, adding to the operational burdens of these companies. White House officials described the move as "similar to China's existing licensing system for rare-earth materials" and rejected concerns that it represented a "new trade escalation," according to the Wall Street Journal.

On this issue, the US has not only ignored the interests of companies operating in China, but it has also attempted to link chip equipment licensing to China's export controls on rare earths - compounding one mistake with another.

First, naturally, chip equipment and rare earths are very different. As rare earths are clearly dual-use items with both civilian and military applications, China generally allows the resources' civilian use, as long as companies or other entities in the market comply with the relevant regulations in China and submit an application. However, as for rare earths' military applications, it is necessary for China to manage the issue differently based on its responsibility to maintain global security.

On the other hand, chipmaking equipment is a typical type of industrial infrastructure primarily licensed for use in civilian high-tech industries; thus, by drawing a false parallel between its civilian-sector controls and China's differentiated management of rare earths for military and civilian use, the US is fundamentally conflating two distinct issues.

Second, the tightening of the US chip equipment licensing system is aimed at China's high-tech industries, but it is the China-based operations of major global semiconductor manufacturers that suffer first. China is not only the world's largest market for semiconductor equipment, but also a key source of semiconductor products. With a steadily growing market and a comprehensive industrial chain, leading semiconductor manufacturers have expanded their production in China over the past few years - and have gained good profits.

The US' move to set up barriers on chipmaking equipment is ultimately aimed at curbing the development of China's semiconductor industry - while also attempting to prompt foreign companies to shift their chip production out of China. However, Washington has underestimated the importance of the Chinese mainland to these companies' revenues and supply chains, as well as the enormous costs involved in relocating production capacity.

Finally, unlike rare earths, US chipmaking equipment is not irreplaceable. In August 2022, then US president Joe Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act to establish a systematic regulatory framework aimed at blocking China's ability to produce advanced chips. However, the US still does not hold absolute control over the semiconductor industry: Its semiconductor equipment companies account for only about one-third of the global market share. Washington also relies on the cooperation of governments and companies in countries, such as the Netherlands and Japan, and must take into account the interests of major global players in the industry.

In the long run, the US' ban on chipmaking equipment is essentially becoming a catalyst for the global semiconductor supply chain's "de-Americanization." Companies like ASML and Japan's Tokyo Electron are more than willing to step in, while China's domestic equipment makers have already achieved scaled breakthroughs in substitution. The "de-Americanization" of China's chip equipment sector was already gaining strong momentum through indigenous innovation. Rather than curbing this trend, US sanctions have only accelerated it - driven by the logic that "a technological blockade compels independent breakthroughs."

Former US under secretary of commerce for industry and security, Alan Estevez, had hoped that China's advanced chipmaking equipment would "break down," so that China could be dealt a blow as long as US companies do not provide components and services, according to Bloomberg. However, with China's constant progress in homegrown chip innovation, this goal has become empty talk. It has become a consensus within the Chinese chipmaking industry that US chip sanctions against China are ultimately doomed to fail.

Although some companies have taken a cautious stance on compliance under pressure, the global semiconductor industry has made its real choices through actions. NVIDIA, for example, has continued to release China-specific GPUs despite repeated restrictions. This strategy essentially reflects the industry's objective recognition of the irreplaceability of the Chinese market and confirms the inherent limitations of unilateral sanctions in the face of a globalized supply chain. As Chinese fabs' mature 28nm process capacity is projected to rise to 25 percent of the global total, the US' attempt to sever the supply chain through administrative means is gradually being undermined by the dual forces of market dynamics and technological progress.

The author is a research fellow at the Society for Technology and Strategic Trends. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn