IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

China-bound atoner under fire: Why did a former Unit 731 member's apology sting Japan?

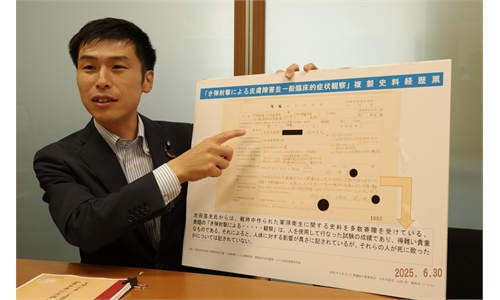

Hideo Shimizu grants an exclusive interview to Global Times at his home in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, on July 1, 2025. Photo: Xu Keyue/GT

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. Yet in Japan, the concealment of historical truth persists. Why is the Japan's younger generation so severely disconnected from its modern history of aggression? Why do the inquiries raised by a lawmaker and the repentant apologies of a war veteran to China deeply wound Japan? How do Japanese civil forces persist in uncovering the truth under such circumstances? When "irrefutable evidence" collides with "sophistry," when perpetrators deliberately forget, who will preserve the memory for tens of millions of victims?

The Global Times launches the "Uncovering Evidence in Japan" series, engaging in direct dialogue with those involved through exclusive interviews with firsthand witnesses, using the truth as a blade to slice through the silence. Only by confronting and remembering history can we safeguard the peace of the future.

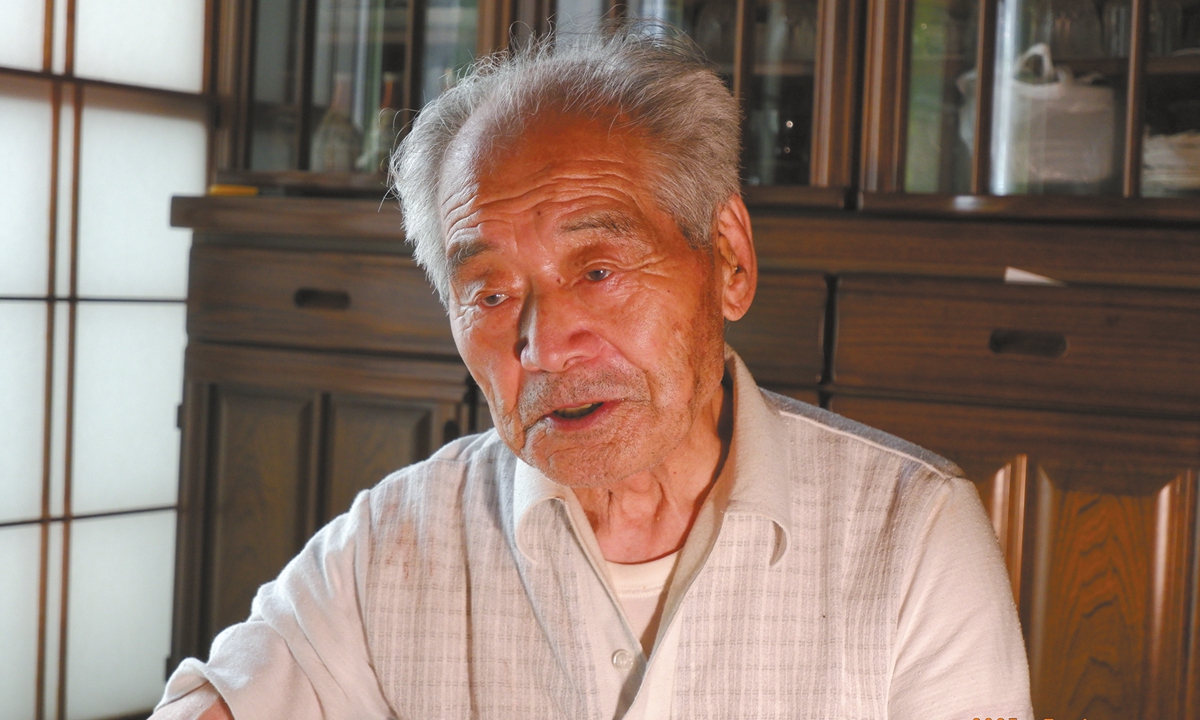

In March 1945, Hideo Shimizu, not yet 15 years old then, was sent to Harbin as one of the last teenage recruits of the Japanese Imperial Army's Unit 731. Seventy-nine years later, the 94-year-old Shimizu returned to Harbin to repent and apologize in 2024. This was his first trip abroad and his first return to China since World War II.

Yet, his public testimony about historical truths has subjected him to immense pressure. Numerous Japanese right-wingers have attacked him, calling him a "liar," "traitor," and "manipulated." His once-close daughters have severed ties with him. Shimizu told the Global Times that many Japanese politicians would prefer he stay silent. but "I don't regret apologizing! Because I've always believed it was something I had to do!"

'All I did was tell the truth. Why am I being accused like a defendant?'

Miyada village is located in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. It was here in July 1930 that Shimizu was born. As the car carrying Global Times reporters wound its way along the mountain road, a derelict house came into view, its door still bearing the clearly visible sign of "Shimizu Construction Co, Ltd." After returning to Japan following the country's defeat, Shimizu spent most of his life making ends meet through this family-run company.

Prior to the visit, the reporters had spoken with Shimizu multiple times by phone. Despite his advanced age, his memories of those days remained clear. Shimizu recalled that in March 1945, when a schoolteacher asked if he wanted to go to China, he thought to himself, "Probably to work in a military supply factory or something similar." And so, Shimizu was sent to Harbin as one of the last teenage recruits of Unit 731, where his main task was extracting plague bacteria from rats.

"I was only 14 then, completely inexperienced, and had no idea what I was really doing," Shimizu paused before continuing, "It was only later that I learned the [plague bacteria] was used in human experiments."

On August 12, 1945, Shimizu received orders to transport explosives and destroy evidence of Unit 731's crimes before retreating. As night fell on August 14, he fled China with the defeated Japanese troops. During his over four months with Unit 731, Shimizu witnessed rows of formaldehyde-filled jars in the specimen room containing fetuses, infants, necks, hands, and various human organs.

After returning home, Shimizu married, raised children, and operated his small business, outwardly living an ordinary life while concealing a terrible secret. "The cruelty of what we did [in Harbin] haunted my thoughts constantly - I could never forget it for the rest of my life," Shimizu said.

During the interview, Shimizu became reluctant to revisit his past with Unit 731. When asked why he was warned against taking part in any medical work upon leaving the unit, yet his superiors became university professors and even opened hospitals, Shimizu, previously calm, grew suddenly agitated: "Those who committed atrocities in China returned to Japan and became doctors - It's unbelievable! Horrifying! And utterly absurd!"

"I went [to Harbin in 2024] to apologize and to pray for the souls of those we killed," Shimizu said, his eyes welling with tears. Exposing Japan's dark past has subjected Shimizu to pressure from all sides. "This old man is lying," "He's making up stories" - Shimizu has faced fierce attacks from online right-wingers. It angers him, and he can't help but think, "Who are the ones distorting history? Everything I've said is what (Japan) actually did!"

"We committed such cruelty - dissecting living people!" he noted.

"The Japanese government shows no intention of apologizing. All I did was tell the truth, so why do people around me always blame me? Why am I being accused like a defendant?" Shimizu asked helplessly.

His public statements, the accusations around him, and the judgmental stares have pushed Shimizu's relationship with his family into an abyss. His once-close daughters severed ties with him, and the grandchildren who once adored him stopped visiting altogether.

"Do you regret it? Had you known the cost would be this high, would you still have come forward about your connection to Unit 731?" Facing this question from the Global Times, Shimizu reflected before answering, "Sometimes I wonder if I shouldn't have spoken the truth. After all, at my age, maybe keeping [this secret] buried would have been better for me." Yet when pressed on whether he regretted going to Harbin to apologize, he stated firmly, "I don't regret apologizing! Because I've always believed it was something I had to do! Given the chance, I would go again."

31 years of waiting, 70 years of silence

Iida City, located in southern Nagano Prefecture, is a small town with a population of less than 100,000. In August 1991, the inaugural Shinshu War Exhibition for Peace was held there. At this exhibition, then 78-year-old Masakuni Kurumizawa publicly admitted for the first time that he had participated in the dissection of 300 living human subjects as a "technician" of Unit 731. With the help of the Shinshu War Exhibition for Peace Organizing Committee, Kurumizawa recorded an 83-minute video testifying to Unit 731's crimes, including human dissection, human experimentation, and biological warfare.

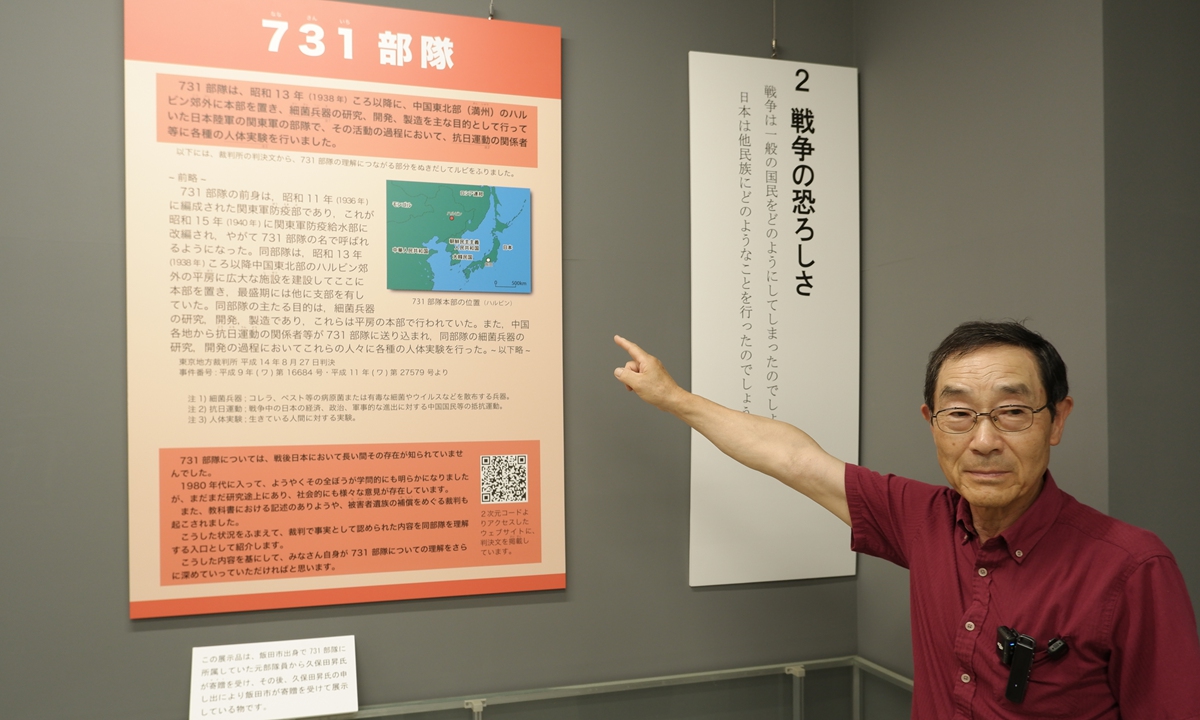

Hideaki Hara, 76, has been a member of the exhibition committee since that time. In an interview with the Global Times, he recalled, "We filmed Masakuni Kurumizawa's video testimony ourselves, using amateur equipment and techniques. Before he passed, he said that this evidence could be used at any time to expose the crimes of the Japanese government."

Moreover, at the 1991 exhibition, Kurumizawa displayed medical instruments and books he had brought back from Unit 731. Hara explained that before fleeing in August 1945, Unit 731 destroyed nearly all its documents and records. Kurumizawa secretly brought these medical instruments and books back to Japan. The medical books bore the stamp "Ishii Unit," which refers to the notorious founder and leader of Unit 731, Shiro Ishii.

Kurumizawa's testimony drew significant attention in Iida. The inaugural 1991 exhibition attracted 2,685 visitors. In a survey conducted at the time, 64 percent of respondents said that the temporary thematic exhibition should be made permanent. Consequently, civic groups repeatedly petitioned Iida City to establish a Peace Memorial Museum.

Kurumizawa decided to donate his evidence to the future memorial museum, but he passed away in 1993 before he could realize it. After years of applications, discussions, petitions, and deliberations, the Iida City Council finally approved the museum's establishment in 2000. It had taken nearly a decade for this grassroots campaign to persuade the Iida City Council.

To collect exhibition materials, Iida City Board of Education formed a "peace materials collection committee." Working tirelessly toward the museum's early opening, Hara and others had gathered over 1,800 exhibits across Nagano Prefecture by 2022. Hara told reporters that year they finally received confirmation the memorial museum would open in May - 31 years after the 1991 exhibition.

Meanwhile, the Shinshu War Exhibition for Peace continued to be held annually. In 2015, when Hideo Shimizu visited the exhibition with his wife, he acknowledged his ties to Unit 731 for the first time - breaking 70 years of silence on the matter.

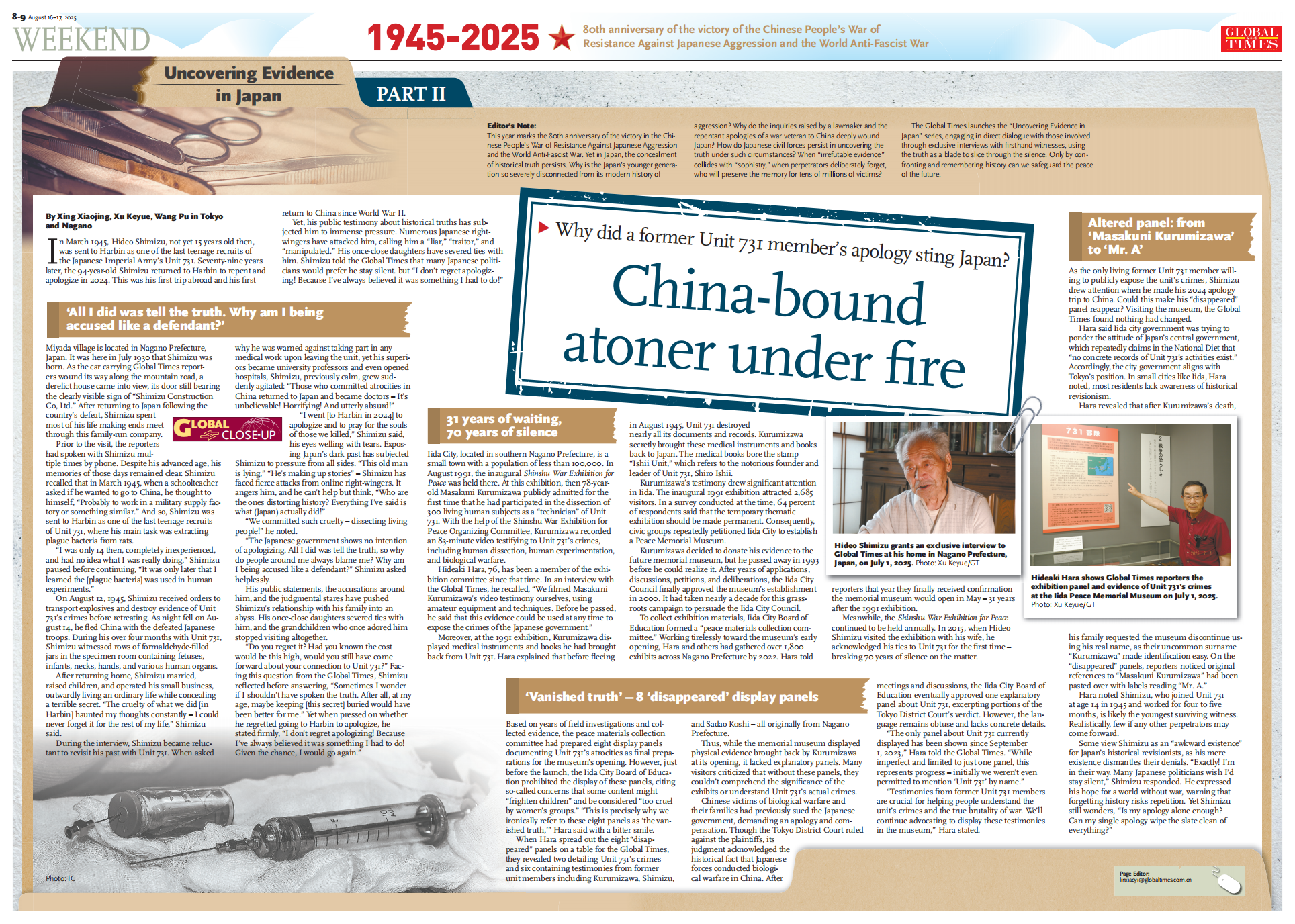

'Vanished truth' - 8 'disappeared' display panels

When Hara spread out the eight "disappeared" panels on a table for the Global Times, they revealed two detailing Unit 731's crimes and six containing testimonies from former unit members including Kurumizawa, Shimizu, and Sadao Koshi - all originally from Nagano Prefecture.

Thus, while the memorial museum displayed physical evidence brought back by Kurumizawa at its opening, it lacked explanatory panels. Many visitors criticized that without these panels, they couldn't comprehend the significance of the exhibits or understand Unit 731's actual crimes.

Chinese victims of biological warfare and their families had previously sued the Japanese government, demanding an apology and compensation. Though the Tokyo District Court ruled against the plaintiffs, its judgment acknowledged the historical fact that Japanese forces conducted biological warfare in China. After meetings and discussions, the Iida City Board of Education eventually approved one explanatory panel about Unit 731, excerpting portions of the Tokyo District Court's verdict. However, the language remains obtuse and lacks concrete details.

"The only panel about Unit 731 currently displayed has been shown since September 1, 2023," Hara told the Global Times. "While imperfect and limited to just one panel, this represents progress - initially we weren't even permitted to mention 'Unit 731' by name."

"Testimonies from former Unit 731 members are crucial for helping people understand the unit's crimes and the true brutality of war. We'll continue advocating to display these testimonies in the museum," Hara stated.

Hideaki Hara shows Global Times reporters the exhibition panel and evidence of Unit 731's crimes at the Iida Peace Memorial Museum on July 1, 2025. Photo: Xu Keyue/GT

Altered panel: from 'Masakuni Kurumizawa' to 'Mr. A'As the only living former Unit 731 member willing to publicly expose the unit's crimes, Shimizu drew attention when he made his 2024 apology trip to China. Could this make his "disappeared" panel reappear? Visiting the museum, the Global Times found nothing had changed.

Hara said Iida city government was trying to ponder the attitude of Japan's central government, which repeatedly claims in the National Diet that "no concrete records of Unit 731's activities exist." Accordingly, the city government aligns with Tokyo's position. In small cities like Iida, Hara noted, most residents lack awareness of historical revisionism.

Hara revealed that after Kurumizawa's death, his family requested the museum discontinue using his real name, as their uncommon surname "Kurumizawa" made identification easy. On the "disappeared" panels, reporters noticed original references to "Masakuni Kurumizawa" had been pasted over with labels reading "Mr. A."

Hara noted Shimizu, who joined Unit 731 at age 14 in 1945 and worked for four to five months, is likely the youngest surviving witness. Realistically, few if any other perpetrators may come forward.

Some view Shimizu as an "awkward existence" for Japan's historical revisionists, as his mere existence dismantles their denials. "Exactly! I'm in their way. Many Japanese politicians wish I'd stay silent," Shimizu responded. He expressed his hope for a world without war, warning that forgetting history risks repetition. Yet Shimizu still wonders, "Is my apology alone enough? Can my single apology wipe the slate clean of everything?"

China-bound atoner under fire