Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

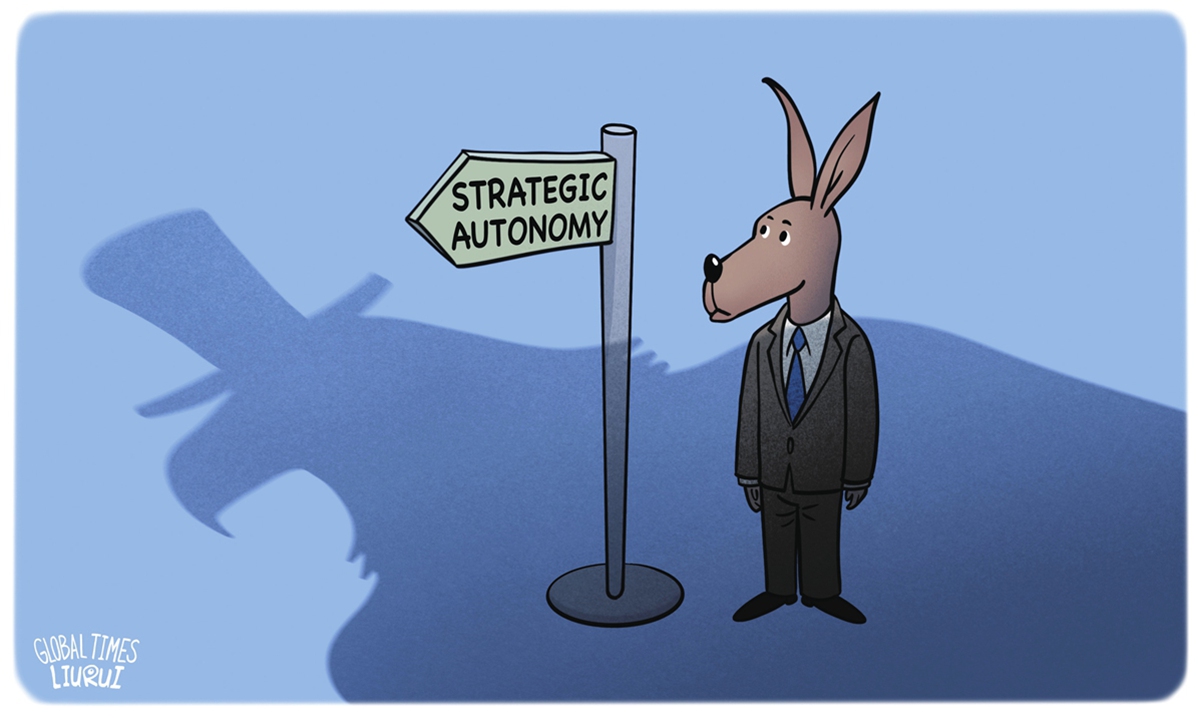

On Monday local time, US President Donald Trump and the visiting Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese signed a critical minerals deal at the White House. With the US leader also assuring the future of AUKUS and praising the bilateral relationship, so far, this has been quite a successful trip for Albanese. Yet behind the handshakes and smiles, the trip reveals something far more consequential: People worry that Australia is once again positioning itself as a loyal junior partner to the US, willing to demonstrate its allegiance even at the expense of its own national independence and long-term interests in the Asia-Pacific.

One has to wonder, is it just a coincidence that, on the eve of the US-Australia leaders' meeting, Canberra chose to publicize the "unsafe" encounter between an Australian P-8A surveillance aircraft and a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea? The timing was too precise to ignore. By making the incident public just as Albanese's plane was heading to Washington, Canberra clearly sought to play up the "China threat" narrative for an American audience. It is plain to see that the gesture is not a defense of sovereignty, but a well-rehearsed political stunt, one designed to reassure the White House that Australia remains an unquestioning member of the US-led camp.

Although the trade between China and Australia has shown resilience in recent times, the underlying confidence has not fully recovered. China remains Australia's largest trading partner, accounting for more than one-third of its exports. But Canberra's recent rhetoric continues to send mixed signals. It welcomes renewed trade flows, while fanning the "China threat" narrative to justify military build-up. Such contradictions reveal a lack of strategic clarity and a dangerous overreliance on US approval as the yardstick of foreign policy legitimacy.

The Washington summit further highlights this imbalance. The focus on rare earth cooperation and defense technology under AUKUS has been presented as evidence of "shared strategic vision." In reality, it was a demonstration of submission. The push to create a US-dominated critical minerals supply chain is framed as economic diversification, but it is, in essence, an attempt to exclude China from sectors where it has long been a leader and a reliable partner. For Canberra, promoting rare earth cooperation is less about industrial strategy and more about offering a political token and a loyalty oath to prove how valuable it is to Washington.

Such short-sighted diplomacy carries heavy costs. By subordinating its regional policy to US strategic needs, Australia risks alienating its neighbors and constraining its own diplomatic space. Moreover, the South China Sea is not Australia's sphere of influence - it is China's sovereign waters, where Beijing's territorial and maritime rights are grounded in history and law. Yet Canberra continues to follow Washington's lead, sending military aircraft and warships into the area under the pretext of "freedom of navigation." Such behavior does not uphold international order; it challenges China's sovereignty and undermines regional peace. For Australia, this approach is profoundly self-defeating.

It is frustrating that as China-Australia relations move beyond stabilization toward further development, Canberra is trying to inject friction just before the US meeting, reflecting an anxiety that unless it loudly echoes American talking points, it may be seen as insufficiently loyal. But loyalty that comes at the cost of sovereignty is no virtue; it is strategic dependency.

Australia's leaders should remember that national interest is not measured by applause in Washington, but by the stability and prosperity of its own region. China and Australia are natural partners in trade, climate cooperation, education and innovation. The complementarities between their economies are structural, not accidental. Undermining this partnership for the sake of US strategic theater only weakens Australia's autonomy.

In the long run, what threatens Australia's security is not China's development, but Canberra's own inability to think and act independently. The more Australia allows itself to be used as a tool in US geopolitical games, the less secure it will become. The Asia-Pacific needs bridges, not barricades.

Australia needs to pursue a truly independent foreign policy. True friendship with the US does not require hostility toward China. A mature, confident Australia should be capable of engaging both major powers based on equality, respect and mutual benefit. Only by regaining its balance can Australia ensure that its future is shaped in Canberra - not scripted in Washington.

The author is a professor and director of Australian Studies Centre at East China Normal University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn