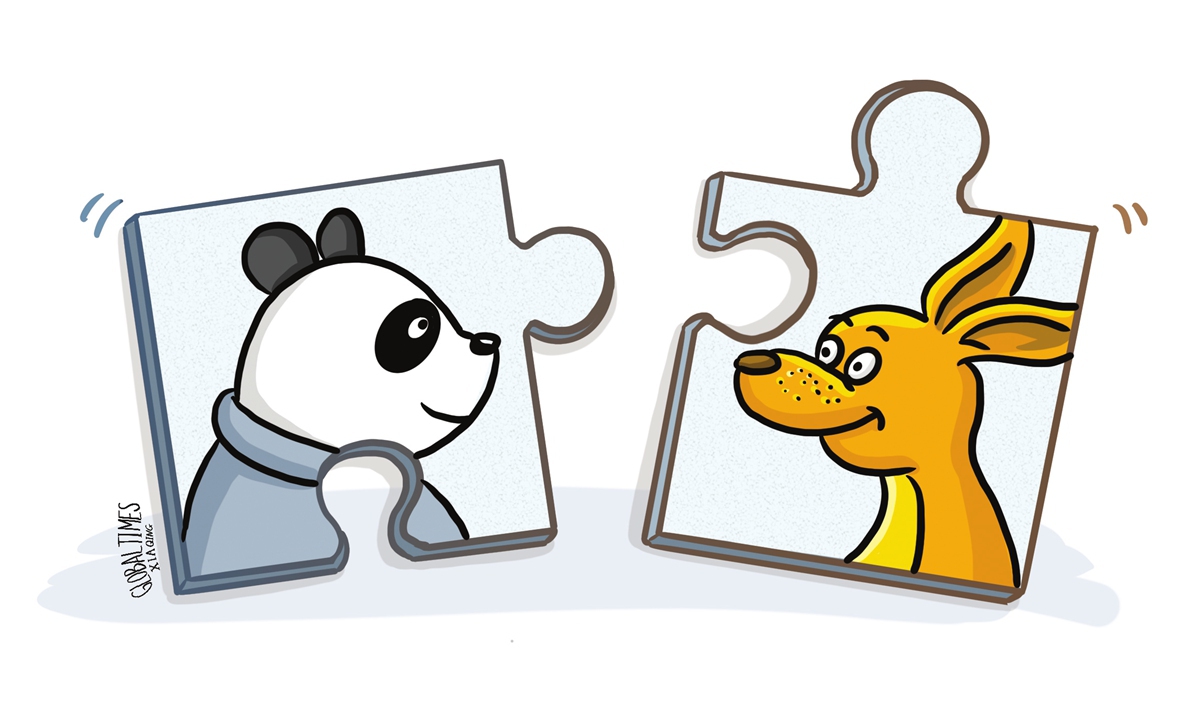

Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

In 1970, a group of Australian academics and community leaders with expertise in Asia released a report urging the Australian government, the business community and the wider public to better understand the peoples of Asia. They warned that Australia cannot afford to remain isolated from the languages and cultures of its nearest neighbors if it is to thrive in an interconnected world.

Historically, Australia's relationship with Asia has been ambivalent - rooted as much in fear and anxiety as in cooperation. This 1970 report was the first of several national-level reviews - seven in total - calling for Australia to build strong capabilities in Asian languages and cultural knowledge. In 1988, Dr Stephen FitzGerald, appointed by the Gough Whitlam administration as Australia's first ambassador to the People's Republic of China in 1973, urged his country to become "Asia literate."

Yet, more than 50 years on, the two questions remain: After decades of official calls for Asia literacy, has Australia truly met this goal? If not, why not?

The urgency of these questions is underscored by growing hostility toward immigration, public disparagement by some elected representatives and troubling incidents of violence directed at non-White communities, including Australians of Chinese heritage.

Some progress has been made. Since the 1970s, Australian schools have introduced and promoted key Asian languages - Chinese, Japanese, Bahasa Indonesia and Korean - chosen for their trade and security relevance. Hindi, widely spoken in India, has also featured in some programs. Bilateral ties with Asian nations have deepened and diversified over time, reflecting the significance of these educational efforts.

However, a 2024 academic study observed that despite numerous policies, programs, and significant financial investment in "Asia literacy" and greater fluency in Asian languages, participation in the four key Asian languages continues to decline. The reasons are complex. A crowded curriculum makes language study seem optional rather than essential. Many Australians continue to view English, still perceived as the global lingua franca, as sufficient for international engagement. Universities, facing chronic funding pressures, often cut humanities and social sciences programs first - Asian studies and language departments have been frequent casualties.

The recent launch of a federal parliamentary inquiry into Asia knowledge and capability within the Australian education system is a commendable and timely initiative. As noted above, a clear disconnect has persisted between Australia's national ambition to be an Asia-literate nation and the tangible outcomes on the ground. This inquiry provides a vital platform for educators, business leaders, ethnic communities and students to voice their experiences and chart a more effective path forward.

A critical line of questioning for the inquiry must be a rigorous diagnosis of why previous strategies have fallen short. Is the issue one of funding, curricular crowding and a lack of qualified teachers, or a deeper, more systemic reluctance to fully embrace Asian languages and studies as core priorities? We must move beyond superficial explanations and confront the underlying barriers that have stifled progress.

Therefore, the ultimate measure of this inquiry's success will not be the volume of its final report, but the quality of its actionable recommendations. Australia cannot afford another cycle of well-intentioned but vague platitudes. The outcome must be a commitment to practical, long-term and cross-sectoral initiatives. This means proposing concrete steps, such as funded pipelines for teacher training, innovative school-university-business partnerships and integrating Asian literacy across diverse subjects from history to science.

By learning from the shortcomings of the past, this process can finally translate Australia's long-stated aspirations into a sustainable national capability, securing Australia's future prosperity and strategic relevance in the region.

In today's interconnected world, genuine understanding across cultures is more important than ever. For Australians, learning the languages and cultures of their Asian neighbors is not simply pragmatic - It is an act of respect and a safeguard against ignorance and prejudice. When political elites use divisive rhetoric or when misinformation fuels xenophobia, Asia literacy equips citizens to respond thoughtfully and build harmony rather than division.

The re-elected Anthony Albanese administration has both the mandate and the responsibility to honor its commitments to Asia literacy, to reverse declining participation and to ensure that studying Asia's languages and cultures becomes a mainstream priority. Strengthening these skills will benefit all Australians and reinforce Australia's role as a trusted and engaged partner in the region.

The author is a professor of the Australian Studies Center of Beijing Foreign Studies University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn