ARTS / ART

Intangible inheritor carves myths and memories in wood

Art and dedication

Chen Zenghuang paints a sculpture in Canghaicuo in Jinjiang, East China's Fujian Province. Photos: Courtesy of Chen Zenghuang

In a quiet corner of a traditional village in Jinjiang, East China's Fujian Province, stands an old house known as Canghaicuo, literally "the Hidden Sea Harbor." Time has softened its red bricks and curved eaves, yet stepping through its narrow doorway feels like entering another world.Inside a century-old home, 21 vividly colored deity sculptures stand in silence, surrounded by a sweeping mural of divine figures. Unlike conventional Buddhist icons, these deities possess an almost earthly vitality, each telling a creation myth born of the deep connection to the sea of Quanzhou, the starting point of the maritime Silk Road.

For one of their creators, Chen Zenghuang, the project was both familiar and foreign. As the fifth-generation inheritor of Zhepingguo Buddha Sculpting, a Jinjiang-listed intangible cultural heritage, Chen has spent decades carving traditional Buddha statues for temples across southern Fujian. But the sculptures of Canghaicuo, using ancient techniques to retell local maritime legends, became a turning point in his creative life. "It's still wood, still lacquer, still the same tools," Chen told the Global Times, "but what I'm shaping now is a story of where we come from."

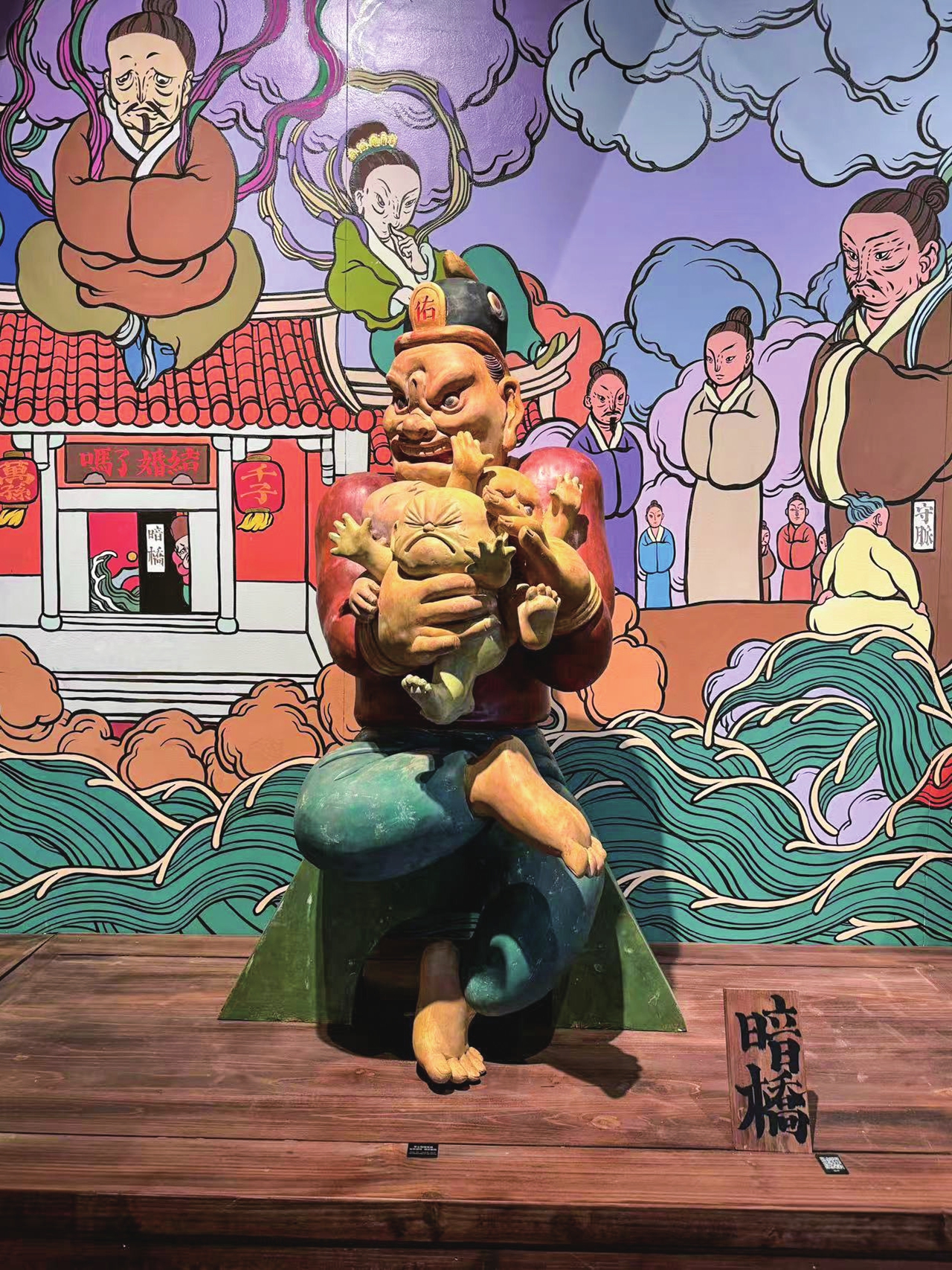

Anqiao, an innovative wood-carved sculpture inspired by Minnan mythology

A legacy of faithThe Zhepingguo school of Buddha sculpting traces its origins to the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Chen's ancestors migrated from Pingyang, East China's Zhejiang Province, to a village in Quanzhou more than a century ago, traveling south in search of work.

They established a small workshop named "Zhepingguo," a poetic nod to their homeland, Pingyang, and their aspiration to merge skill with devotion. Over generations, the Chen family's workshop became renowned across southern Fujian for its refined lacquer-thread sculpture, known locally as zhuangfo, or "Buddha dressing."

This craft involves more than carving. Each statue, often made of camphor wood, passes through nine distinct stages, including drafting, rough carving, applying lacquer threads, painting, and adding ornaments. "Every step is handmade," Chen explained. "Each cut is a subtraction. You don't add to the wood, you remove what doesn't belong, until the divine shape reveals itself."

Among all the steps in zhuangfo, Chen finds lacquer-threading the most demanding. The process involves mixing lacquer, tung oil, and natural fibers to form a paste that is rolled into strands as fine as a single hair. With steady hands, the artisan then winds these strands across the sculpture's surface to create flowing drapery, halos, and ornaments. "The first year, I couldn't make a single straight line," Chen said. "You need your heart to be as calm as still water. Any tension, and the thread snaps."

The results, however, are extraordinary. The lacquer threads harden into raised reliefs that shimmer beneath a layer of gold leaf, giving the deity's robes a lifelike movement. Chen takes the antique Guandi statue as the perfect example of the craft's longevity. Beneath its gleaming surface lies a base of yellow kaolin clay, chosen for its breathability and resilience. Even after more than 100 years, the intricate lines remain unbroken.

Chen grew up amid the rhythmic tapping of mallets and the scent of tung oil. His father, Chen Tianyou, a craftsman with more than 40 years of experience, instilled in him a quiet discipline: no shortcuts, no compromises. "My father could tell if my carving was uneven just by the sound of the chisel," Chen said. Determined to deepen his skills, he later enrolled in the Xiamen Academy of Arts and Crafts, majoring in sculpture. "At school, we worked mainly with clay," he recalled. "Clay is forgiving, you just add and shape. But wood is final. Once the blade cuts, there's no going back." The transition was painful: his hands blistered, his fingers bled. Yet, each mark became a lesson in patience. Over time, Chen discovered that carving was not merely a technique but a dialogue between material and spirit. "When the chisel moves along the grain," he said, "you can feel the wood breathing with you. That's when you understand the meaning of craftsmanship."

At first, he expected every statue he carved to be intended for worship, an object that would one day be enshrined in a temple or ancestral hall, surrounded by incense and prayer. In southern Fujian, such Buddha statues mainly represent local people's connection between humans and the divine, between family and faith.

"In our village," Chen said, "when a new god is invited to the temple, everyone joins in, the musicians, the elders, the children. The statue becomes a bridge between us and our ancestors."

Traditional Zhepingguo Buddhist sculpture

Tradition and innovationHowever, for Chen, mastery of tradition is only half the journey. Innovation, he believes, is the soul of inheritance. His collaboration on Canghaicuo with contemporary artist Wen Na has become a landmark in his career, blending craftsmanship with modern storytelling.

The sculptures they created together, such as Fenxiang, which depicts migrants carrying incense across oceans, and Anqiao, symbolizing the invisible bridges that link descendants with their ancestral temples, translate the spiritual language of wood into narratives of migration, memory, and belonging.

Other works in the series draw from Quanzhou's maritime folklore. Rongshen shows celestial beings treading on constellations, seeking a place of peace in an ever-expanding world, while Huashou transforms the traditional "sending off the king" ritual into a symbol of homecoming, where paper boats set sail not to depart, but to return.

For Chen, these mythic figures are not departures from tradition but extensions of it. "I'm surprised on how faith and Minnan culture could be depicted in these new figures when Wen Na handed me the drafts," he said, "and the essence of Buddhism and folk belief is compassion, remembrance, and return. These are the same emotions felt by our ancestors who crossed the seas. I only give them form through wood."

His work has also inspired a younger generation of carvers to approach zhuangfo with renewed curiosity. After Zhepingguo Buddha Sculpting was officially recognized as an intangible cultural heritage of Jinjiang in 2016, Chen and his father have begun teaching apprentices, hoping to ensure that the art once confined to temple workshops finds a sustainable future.

"People think of carving as old-fashioned, but every mark of the chisel is a record of time. It's history in motion," Chen said.

Just like the figures in Canghaicuo: part myth, part memory, both ancient and immediate, Chen sees the act of carving as a meditation on continuity. "Our task is not to preserve the tradition in a jar, but to keep it flowing."