South Pacific exploration of ‘Da Yang Hao’ signals a rising power’s peaceful research voyage

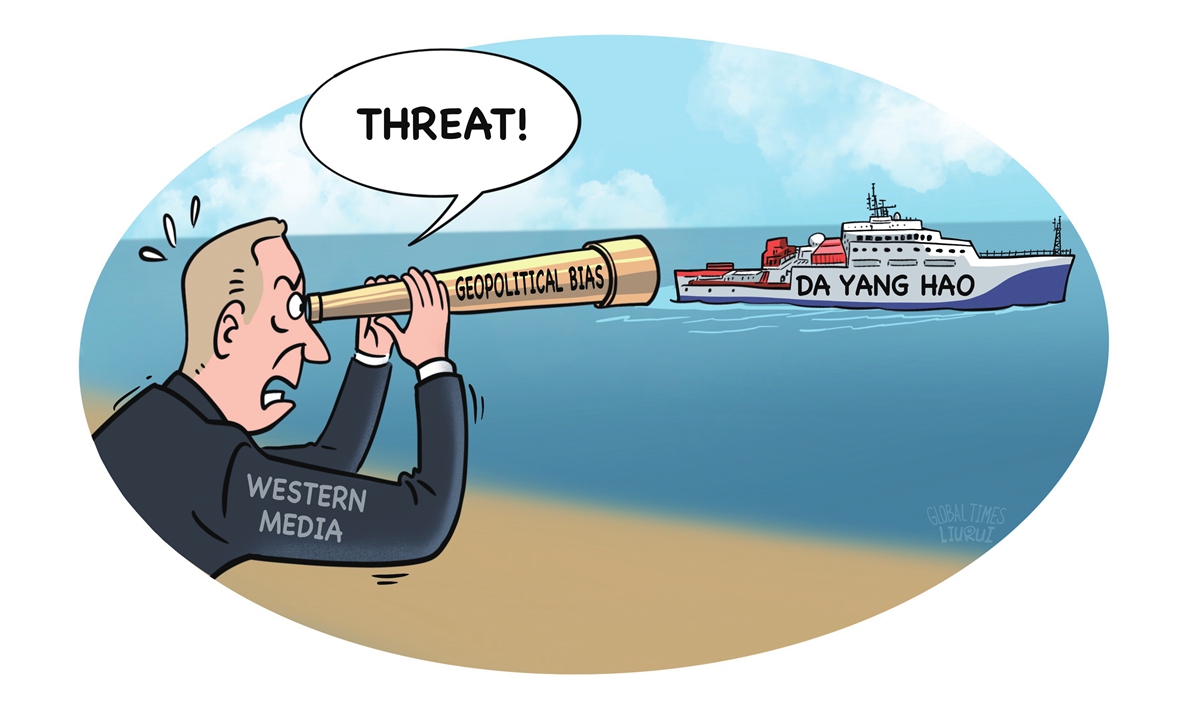

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

According to AFP News, the Chinese research vessel Da Yang Hao docked at Avatiu Port in the Cook Islands in the South Pacific on Saturday.

The ship's mission - to investigate and study the seabed environment and resources - had been approved by the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority (SBMA), and local representatives were on board. All data, the SBMA said, would be made publicly available. Still, headlines in Western media outlets buzzed with alarm. For example, AFP News said "Chinese research vessels have been accused of carrying out surveillance and other military activities under the auspices of scientific work."

For the West, this ship represents not only a security risk in the literal sense, but a psychological one: a reminder that the South Pacific is no longer a geopolitical echo chamber of the old colonial order.

Operated by China's Ministry of Natural Resources, Da Yang Hao is an oceanographic vessel that is 98.5 meters long, has a crew capacity of 60 people, is capable of conducting integrated geological and geophysical surveys, and is equipped with a 6,000-meter-class autonomous underwater vehicle. Its focus is scientific, and its technology is civilian. Yet its smooth operation in a region long considered the "Anglo-Saxon world's backyard" has unsettled many in the West.

To understand that unease, one must recall how the Pacific was once mapped - both literally and politically. In 1888, Britain declared the Cook Islands a protectorate, linking them to New Zealand as part of an imperial network. Royal Navy ships would take supplies there, missionaries followed, and the islands were placed under the administrative control of the British High Commissioner of the Western Pacific.

Even after the Cook Islands achieved self-government in 1965, the region remained framed through Western eyes: an isolated arc of tropical dependencies, strategically managed from afar.

Today, however, the world is very different.

China has the capability and motivation to explore the deep sea in a peaceful and collaborative manner. For Pacific Island Countries facing economic and climate challenges, Chinese scientific partnerships offer not coercion but capacity-building - training local researchers, mapping mineral resources and potentially enabling revenue from peaceful utilization of marine resources.

History offers a sharp contrast. When the Royal Navy first sailed these routes, it came with cannons and cartographers. Modern China arrives with sonar arrays and sediment samplers. It's the method that matters: One imposes knowledge through empire, while the other proposes knowledge through cooperation.

To Western observers steeped in the legacy of sea power, any Chinese ship in the Pacific evokes strategic reflexes inherited from the 19th century. The truth, however, is more straightforward and pragmatic: a self-governing Pacific nation has invited a capable partner to collaborate on legal and transparent scientific research.

The map is changing shape.

The Cook Islands, Fiji and others are asserting agency over their waters, choosing partners based on economic and technological merit. China's involvement marks this broader democratization of oceanic space.

The Da Yang Hao's voyage signals a healthy normality: scientific cooperation by a rising power that is not conquering, but participating. If the West feels threatened by this, the discomfort lies in its own reflection - in realizing that its historic monopoly on defining the ocean's meaning has come to an end.

To accept this transformation requires shedding the reflex that equates Western absence with instability. That world will not be divided by gunboats, but connected by research vessels - each one taking soundings not just of the ocean floor, but of the depth of old assumptions.