Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

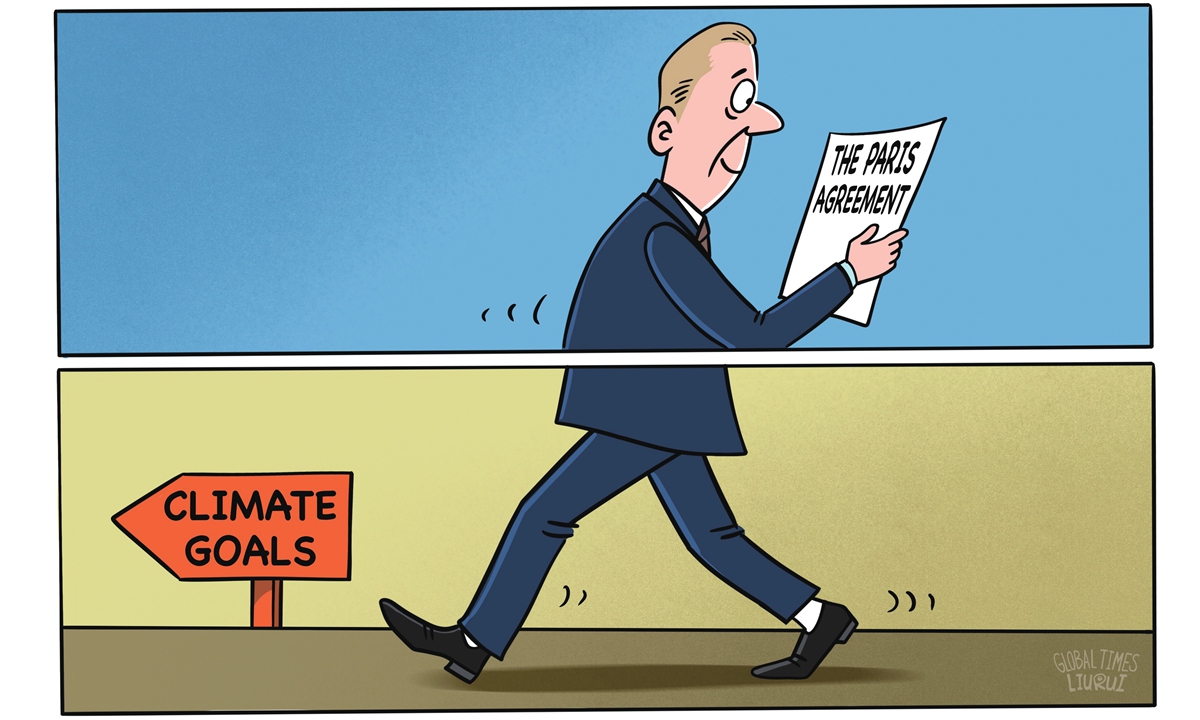

Recently, the EU reached an agreement on amending the European Climate Law and issued a position paper that reflects nominal ambition and substantive compromise.

While the paper retains the nominal target of a 90 percent reduction in net greenhouse gas emissions, it allows member states to use 5 percent international carbon credits and may loosen this by another 5 percent in the future, effectively lowering the EU's real reduction ambition to 85 percent or even 80 percent. This weakened target not only reveals profound internal divergences of interest within the EU but also reflects its deep-seated dilemmas in global climate governance.

Once celebrated as a "climate leader," the EU now faces unprecedented strategic pressure - the most direct manifestation of its standing at the crossroads of global climate governance.

The EU is currently caught between the soaring costs of the green transition and intensifying international competition. It must invest enormous resources to advance the shift toward green energy while simultaneously bearing the pressure of rising energy costs and a relative decline in its industrial competitiveness on the global stage. At the same time, increased defense spending is competing with climate-related investment, forcing the EU to adjust its fiscal and political priorities. Coupled with the dual shocks of the energy crisis and economic downturn, a growing number of member states are raising pragmatic doubts about overly aggressive climate targets.

A deeper driver is the imbalance in transatlantic relations, which constrains the EU's energy autonomy. The US withdrawing from the Paris Agreement for a second time and its formal exit from the Just Energy Transition Partnership have undermined the EU's climate ambition. After the destruction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and the disruption of Russian energy supplies, the EU fell into a structural dependence on US fossil fuels, hindering the progress of its green transition and weakening innovation in related industries. Within this imbalanced landscape, the EU's room to formulate independent climate policies has steadily diminished, and its energy autonomy now faces severe challenges.

The EU's weakened climate goals send a negative signal to the international community, not only undermining other countries' confidence in implementing the Paris Agreement, but also weakening the EU's bargaining power on climate finance and technology transfer. The EU's concessions further provide other countries with an excuse to lower their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) targets, widening the ambition gap in the global response to climate change.

Shifts in the climate policies of the US and the EU are reshaping the geopolitical landscape of climate governance. The US government has explicitly refused to participate in COP30 and has used trade measures to pressure other countries on their climate policies, undermining the foundations of multilateral cooperation. Regarding the NDC submissions, only around 60 parties to the Paris Agreement have submitted their new NDCs on time. This indicates widespread uncertainty among countries regarding the international climate system. The global climate governance framework centered on the Paris Agreement faces the risk of fragmentation, further weakening the basis for collaborative action to address climate challenges.

The EU's decision to expand the use of international carbon credits sends a dangerous signal to developing countries - The credibility of developed countries' climate commitments is declining. In the current global climate governance landscape, marked by the US withdrawal and waning EU influence, China is taking a leading role in green energy investment and the development of new-energy technologies. Leveraging international platforms such as COP30, China actively promotes issues such as global climate justice, earning sustained recognition and support from the Global South countries.

Against the backdrop of energy transition and geopolitical conflicts, the future of global climate governance depends on several key variables: the continuity of US policies, whether the EU can regain strategic autonomy, the collective action capacity of developing countries and the choices of emerging powers. Global climate governance stands at a crossroads, and if great‑power competition outweighs climate cooperation, the ecological risks facing humanity could be incalculable. Therefore, all parties need to seek balance within their shared mission and expand the scope for complementary and collaborative action.

Li Xinlei is a professor at the School of Political Science and Public Administration, Shandong University, and Mo Chunhui is a scholar at the same school. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn