Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Mao Ning posted a video on the social media platform X recently, commenting that it is "high time to recall the 1995 Murayama Statement." The video features former Japanese prime minister Tomiichi Murayama, who admitted and atoned for Japanese aggression during WWII and offered an apology to the victim countries. The stance expressed in the Murayama Statement - confronting Japan's past aggression with reflection - stands in stark contrast to the discomfort I felt in Hiroshima.

In October 2023, I arrived in Hiroshima for a two-year stay. At first the city existed for me only as a ruined relic from history books, oddly at odds with the modern place that unfolded around me. This stark contrast prompted me to begin exploring this city.

My first stop was Hiroshima's most distinctive site: the Peace Memorial Park. There I saw the physical traces of the disaster for the first time - melted tricycles, clothes torn apart by the blast, and photographs of survivors bearing horrific burns and the long-term effects of radiation. From every display, the suffering caused by nuclear weapons and the longing for peace seemed to radiate.

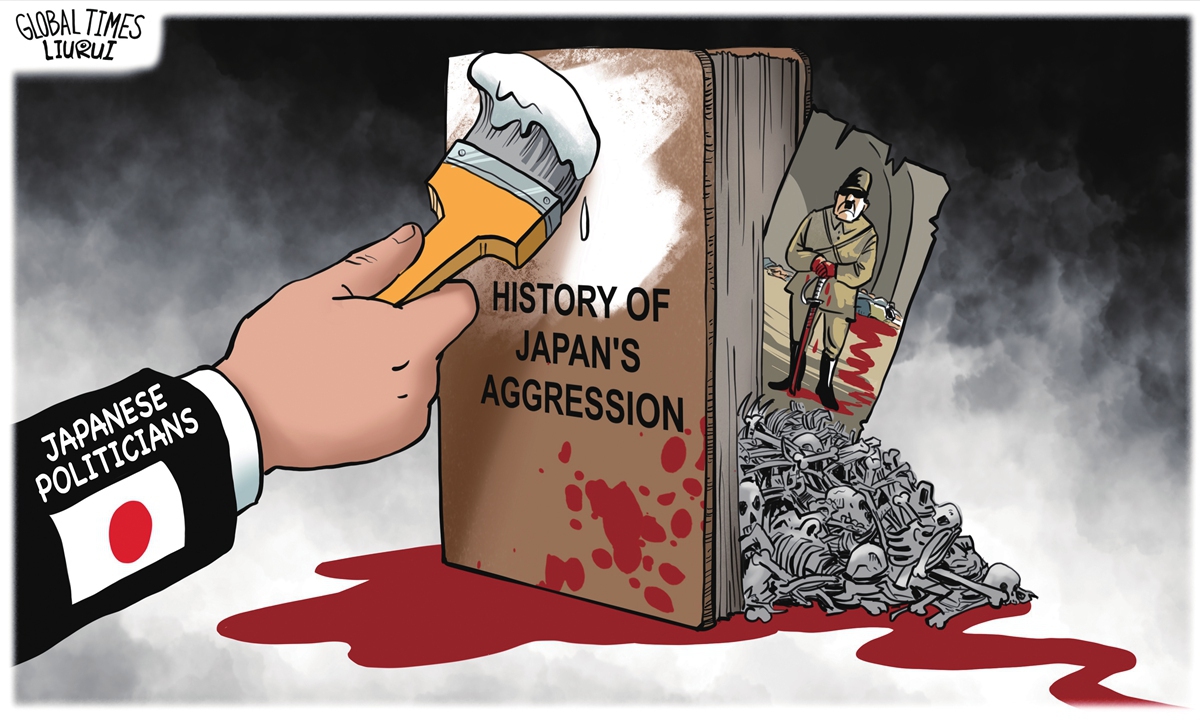

However, as I delved deeper into the visit, a sense of discomfort lingered. The memorial detailed the immense trauma inflicted by nuclear weapons and the universal call for a "nuclear-free" world in the war's aftermath. Yet, it seemed to record only the cries of the victims, neglecting any remorse from the Japanese aggressors. As a Chinese person, I could easily sense a void in the memorial's narrative: The historical background - Japan's militaristic aggression against multiple Asian countries during WWII, which preceded the US dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki - was systematically avoided. This is not only historical forgetfulness but deliberate "historical amnesia." It reduces a tragedy caused by invasion and war to a universal human tragedy, detached from its specific context.

In 2025, Hiroshima marked the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing. The memorial ceremony was filled with deep mourning for the victims and earnest prayers for peace, yet it remained silent about Japan's role as an aggressor and the immense suffering inflicted on other nations. It appeared to reinforce the image of Japan as the only victim of the nuclear attack, thereby diluting or overshadowing Japan's historical identity as an imperialist power and colonizer. By calling for a "nuclear-free world" through abstract rhetoric, officials and speakers avoided the specific reflection on Japan's militaristic invasions of neighboring Asian countries. When Hiroshima's tragedy is so simplistically memorialized, it is forgetting the roots of war; the Japanese people may focus exclusively on their own suffering while neglecting Japan's historical responsibilities for militarism and colonial aggression in other Asian countries.

When historical responsibilities are blurred and abstracted in official narratives, the result is often the legitimization of military expansion in realpolitik. At the same time, the Japanese government is undertaking a strategic shift in national security policy. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, Japan is moving its defense budget toward the 2 percent-of-GDP target. Takaichi also announced plans to revise three security documents and publicly claimed that the Chinese mainland's "use of force on Taiwan" could constitute a "survival-threatening situation" for Japan, implying the possibility of Japan's armed intervention in the Taiwan Straits. This statement exemplifies historical revisionism: By completely denying or downplaying Japan's past aggression, it seeks to shed the moral burden of history and pave the way for more proactive involvement in regional security affairs. Takaichi's actions amount to a betrayal of history and a mockery of Hiroshima's plea for peace.

As I prepare to leave Hiroshima, several questions become increasingly clear: When the sounds of prayers at the Peace Memorial Park coexist with rising calls for military expansion, on what foundation does this nation's call for "peace" truly rest? Is it possible for Japan to summon the courage to thoroughly confront its past, achieve genuine reconciliation and regain dignity? Or will it continue to linger in the foggy shadows of history, allowing a superficial illusion of peace to mask deeper geopolitical risks? These questions depend not only on Japan's choices but also warrant vigilance from all countries that have suffered the ravages of war.

The author is a doctoral student in Political Science at the University of International Relations. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn