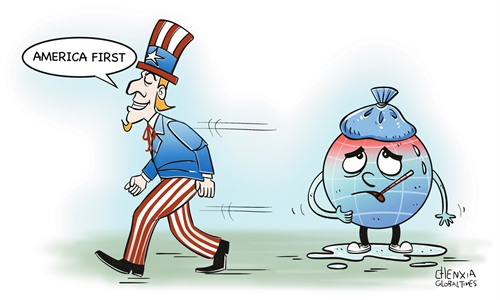

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

From November 22 to 23, Johannesburg hosted the 20th G20 Leaders' Summit under the theme "solidarity, equality, sustainability." On the very first day, leaders adopted the G20 South Africa Summit's Leaders' Declaration by overwhelming consensus.

Opening the summit, South African President and G20 Chair Cyril Ramaphosa underscored the value and necessity of multilateralism. "The adoption of the Declaration from the Summit sends an important signal to the world that multilateralism can and does deliver," he said. That signal was all the more striking because it was sent in the face of open opposition from Washington.

In a diplomatic note ahead of the meeting, the US informed the host government that it would not attend and opposed the issuance of any G20 summit outcome document under the premise of a consensus G20 position without US agreement, according to a document seen by Bloomberg.

As the first African country to chair the G20, South Africa insisted that the leaders' summit proceed as planned, that the declaration be adopted on schedule, and rejected Washington's attempt to send only a chargé d'affaires to the handover ceremony for the next G20 presidency, citing basic diplomatic norms. This stance reflected more than a procedural point; it revealed a quiet but firm diplomatic confidence.

In Johannesburg, US non-participation did not plunge the agenda into disarray. Quite the opposite: Driven by the vast majority of members, consensus on the declaration came earlier and more smoothly than in many previous rounds. The scene pointed to a more profound shift: Today's multilateral mechanisms are gradually freeing themselves from a unipolar logic and moving toward more inclusive frameworks that better reflect diverse interests.

The core issues highlighted in the declaration are rooted in immediate, tangible concerns and a sense of fairness. They include addressing climate change, supporting renewable energy, easing the debt burdens of developing countries and reforming global financial governance. These priorities are not a random list; they reflect the most urgent everyday demands of many developing economies.

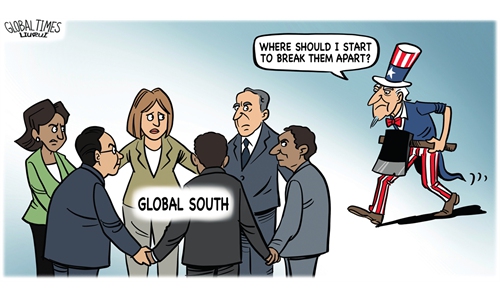

From Africa to South Asia, and from Latin America to Southeast Asia, countries across the Global South are struggling with debt distress, climate vulnerability and industrial transition. What they seek from the international system is not charity, but a more equitable environment in which to develop.

The declaration thus reads as a collective voice of the developing world. It emphasizes cooperation over coercion, stability over confrontation and inclusion over exclusion. In doing so, it implicitly challenges a long-dominant Western policy agenda that has tended to be "security-centric" and "sanctions-driven."

Experience has already shown that the search for global consensus can no longer revolve around the will of a single hegemonic power. Washington's decision to "boycott" the summit is best understood as a strong reaction to its own growing discomfort with this reality. In an increasingly multipolar environment, where more actors expect to be heard, refusing to engage does not preserve influence; it isolates the refuser.

For much of the postwar period, international politics revolved around a single center of gravity. Today's landscape is far more complex. States at different stages of development, in various regions and political systems, are participating in agenda-setting by virtue of their economic weight, technological capabilities, demographic scale and natural resources.

The global system now stands at a crossroads between an aging order and an emerging one. On one side, the US and its allies still command substantial advantages in finance, technology and security architecture. On the other, the political will, economic dynamism and cooperative networks of the Global South are expanding at remarkable speed. In this context, the G20 - as the premier forum bringing together advanced and emerging economies - should serve as a space for coordination, not fragmentation.

This year's summit, therefore, carries symbolic weight beyond its specific declaration. It illustrates a broader trend in global politics: While the inertia of the old order persists, the logic of a new order is becoming irreversible. The world is changing. If the US continues to respond with familiar displays of displeasure - boycotts, walkouts, attempts to block consensus - it may eventually discover that fewer and fewer countries feel obliged to coax it back into the room.