Bearing witness across generations: A family’s promise to remember the Nanjing Massacre

Each time the air-raid sirens pierce the winter air over Nanjing, East China's Jiangsu Province on national memorial day on December 13, local resident Xia Tianxing feels a familiar ache rise in his chest. "I feel overwhelming sadness whenever the sirens sound," Xia said. "They always bring me back to what happened to my mother-in-law."

His mother-in-law, Wang Suming, was a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre. Xia is not only her son-in-law, but also one of the first officially recognized inheritors of the historical memory of the massacre-a role he sees not as an honor, but as a responsibility.

Wang Suming, whose original name was Yang Mingzhu-meaning "the pearl" cherished by her parents-was a two-year-old child when Japanese troops captured Nanjing, then the capital of China, on December 13, 1937. During the ensuing massacre, her father, Yang Daifu, a middle-school principal, was arrested by Japanese invaders on accusations of being a "saboteur" and was then killed. What followed was the complete destruction of a family-Their home was burned to the ground. Her mother, pregnant at the time, lost the unborn child amid the chaos. Her grandmother died in grief.

To save her four children, Yang Mingzhu's mother made the decision to send them away to survive. The siblings were separated and forced into lives of displacement and hardship. Yang Mingzhu lost her family and her name. She was taken in by a poor family surnamed Wang and became Wang Suming-a new name meaning "plain and light," and a new identity shaped by survival.

"That history was branded onto her like a scar," Xia said.

Yet, Wang Suming lived with remarkable resilience. Xia introduced that as a young girl, Wang Suming gathered wild vegetables to survive and worked long hours as a textile laborer. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, she found stable work as a signal operator in a railway communications unit and was later honored as a model worker. In retirement, she devoted more than 20 years to community volunteer work, eventually becoming the oldest volunteer in Nanjing's Qinhuai District during the Youth Olympic Games.

What happened to the young Wang Mingsu was not an isolated tragedy, but one shared by countless Chinese families. After Japanese troops captured Nanjing on December 13, 1937, a six-week massacre followed in which approximately 300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers were killed-one of the most brutal atrocities of World War II.

As a survivor from the tragedy, Wang Mingsu chose to testify. "She stood up and told her story to everyone around her," Xia said. "She wanted people to know what Japanese invaders did to her, to her family and to the country."

In 2007, after the memorial hall reopened following its expansion, she was asked by a Japanese reporter whether she could forgive the Japanese. She answered without hesitation: "No."

The year 2007 was also a turning point for Xia himself. He had learned about his mother-in-law's past after marrying her daughter, but it was during that period that the weight of her experience left a deep impression on him.

From that point on, Xia began collecting books and materials related to the Nanjing Massacre. Later in 2007, when the family attended the reopening ceremony of the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders, a BBC reporter interviewed his daughter and reminded her to use the English term "Nanjing Massacre."

"That was the first time I heard the English expression," Xia said. "From then on, I started paying close attention to how the Nanjing Massacre was reported in English."

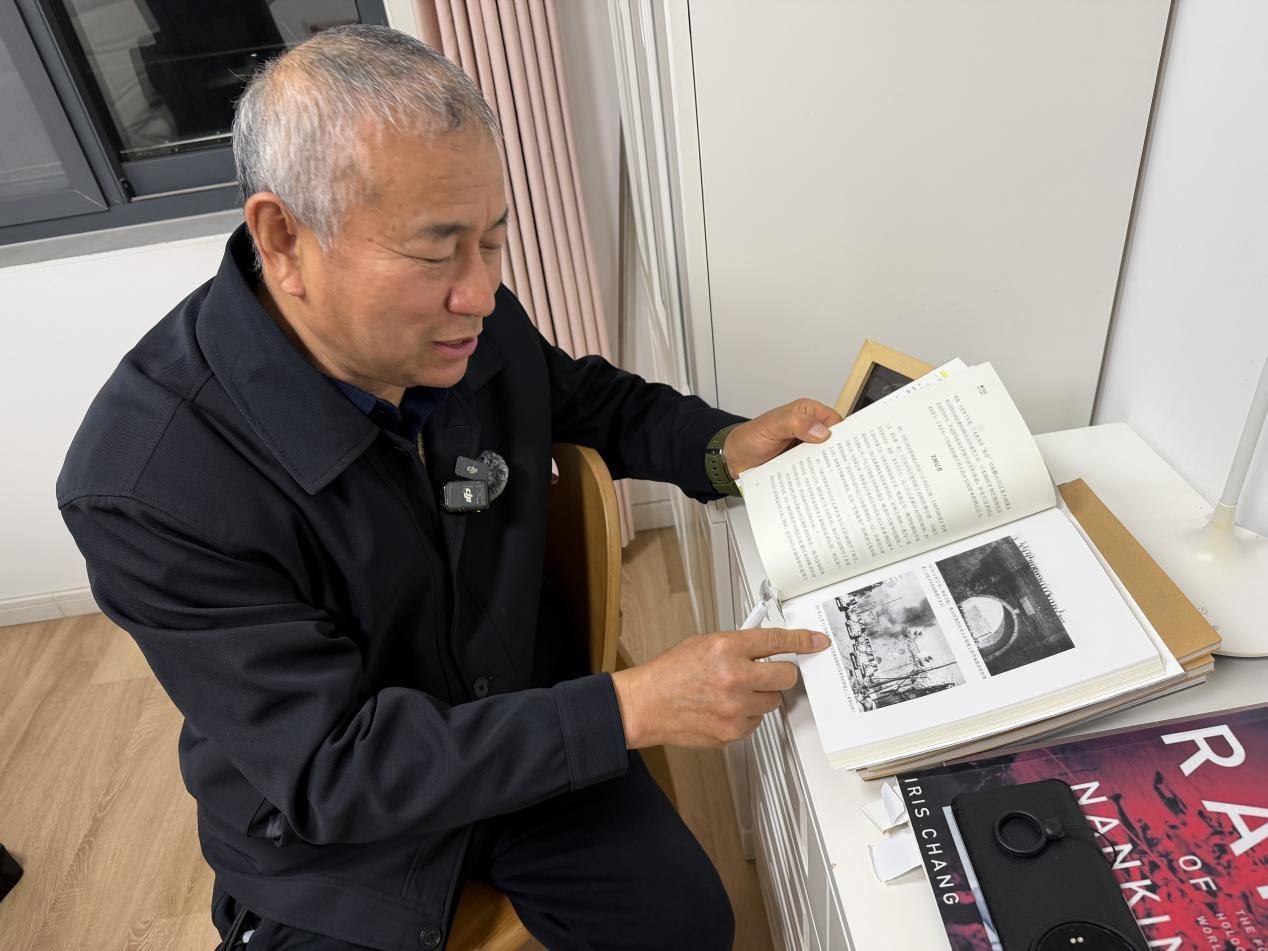

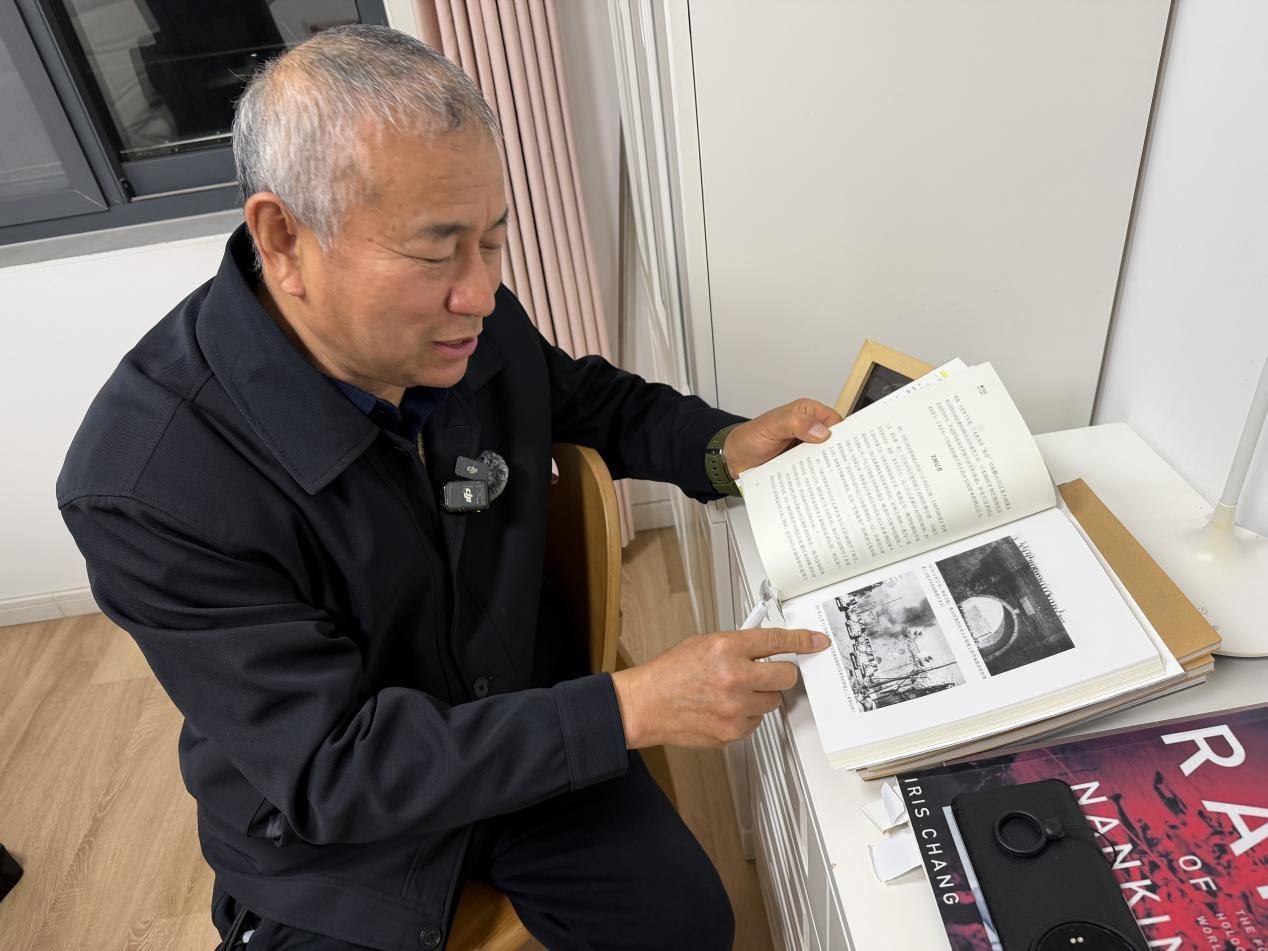

He began reading English newspapers with a dictionary in hand. One day, at a foreign-language bookstore in Xinjiekou, he came across Iris Chang's The Rape of Nanking. After several visits, he decided to buy it. "Since then, whenever I talk about the Nanjing Massacre in English, I follow the terminology used in that book," he said.

As Xia's daughter lives overseas, he frequently traveled abroad and attended gatherings with friends. He soon realized that while many people were familiar with World War II in general, few knew anything about Nanjing.

"I felt I had a duty to tell them," he said. "When they heard that 300,000 people were killed, they were stunned. In some small countries, that number equals the population of an entire city."

Because he was a survivor's family member, his words carried weight. "They believed me," he said.

One of those listeners was an American friend named David. In May 2018, after hearing Xia's account, David traveled to Nanjing with his wife and daughter to visit the memorial hall, accompanied by Wang Suming herself.

She showed them her footprints and handprints preserved at the memorial, and pointed out her father's name on the wall of victims. The family was deeply moved, signing the guestbook and making a donation before they left, according to Xia.

"As inheritors of the historical memory on the Nanjing Massacre, we have the duty to pass this history on," he said. "It must live on as part of our family's memory-and as part of the world's conscience."

That sense of responsibility, Xia said, has taken on added urgency amid growing vigilance over far-right forces in Japan and renewed concerns about the resurgence of militarist thinking. As a relative of the victims, he said, they understand the truth of history most clearly. The massacre, he noted, shattered countless families in an instant-loved ones were brutally killed, children were driven onto the streets, torn from their families, and left struggling even for basic survival.

The denial of the Nanjing Massacre by Japan's right wing is unacceptable to the Chinese people, particularly to the families of the victims, Xia said. The deaths of 300,000 people are not a matter of interpretation, but a conclusion established by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal-supported by irrefutable evidence and beyond any attempt to overturn, he stressed.

At the end of the interview, Xia looked up and, in English spoken with a noticeable accent, repeated the words he has shared countless times with foreigners: "I am from Nanjing, China. I am relative of victim of Nanjing Massacre. In 1937, about 300,000 Chinese people were killed by Japanese invaders. It is fact. It is real. We never forget Nanjing Massacre."

His mother-in-law, Wang Suming, was a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre. Xia is not only her son-in-law, but also one of the first officially recognized inheritors of the historical memory of the massacre-a role he sees not as an honor, but as a responsibility.

Wang Suming, a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre, is accompanied by her daughter Xu Hong and son-in-law Xia Tianxing in December 2014 as she mourned her father, who was killed by Japanese invaders in 1937. Photo: Courtesy of Xia Tianxing

Wang Suming, whose original name was Yang Mingzhu-meaning "the pearl" cherished by her parents-was a two-year-old child when Japanese troops captured Nanjing, then the capital of China, on December 13, 1937. During the ensuing massacre, her father, Yang Daifu, a middle-school principal, was arrested by Japanese invaders on accusations of being a "saboteur" and was then killed. What followed was the complete destruction of a family-Their home was burned to the ground. Her mother, pregnant at the time, lost the unborn child amid the chaos. Her grandmother died in grief.

To save her four children, Yang Mingzhu's mother made the decision to send them away to survive. The siblings were separated and forced into lives of displacement and hardship. Yang Mingzhu lost her family and her name. She was taken in by a poor family surnamed Wang and became Wang Suming-a new name meaning "plain and light," and a new identity shaped by survival.

"That history was branded onto her like a scar," Xia said.

Yet, Wang Suming lived with remarkable resilience. Xia introduced that as a young girl, Wang Suming gathered wild vegetables to survive and worked long hours as a textile laborer. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, she found stable work as a signal operator in a railway communications unit and was later honored as a model worker. In retirement, she devoted more than 20 years to community volunteer work, eventually becoming the oldest volunteer in Nanjing's Qinhuai District during the Youth Olympic Games.

What happened to the young Wang Mingsu was not an isolated tragedy, but one shared by countless Chinese families. After Japanese troops captured Nanjing on December 13, 1937, a six-week massacre followed in which approximately 300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers were killed-one of the most brutal atrocities of World War II.

As a survivor from the tragedy, Wang Mingsu chose to testify. "She stood up and told her story to everyone around her," Xia said. "She wanted people to know what Japanese invaders did to her, to her family and to the country."

In January 2014, Wang Suming, a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre, spoke to the media about her family's experience during the atrocities of 1937. Photo: Courtesy of Xia Tianxing

Before her death on March 23, 2022, at the age of 87, Wang Suming remained willing to take part in memorial activities and to tell others about her experiences. According to Xia, as long as her health permitted, the family accompanied her to the memorial hall each National Memorial Day. Although her father's remains were never recovered and only his name is engraved there, she insisted on attending, breaking down in tears. She knew the visits would reopen old wounds, but said it was important "to let more people know about the atrocities committed by the Japanese army in Nanjing."In 2007, after the memorial hall reopened following its expansion, she was asked by a Japanese reporter whether she could forgive the Japanese. She answered without hesitation: "No."

The year 2007 was also a turning point for Xia himself. He had learned about his mother-in-law's past after marrying her daughter, but it was during that period that the weight of her experience left a deep impression on him.

From that point on, Xia began collecting books and materials related to the Nanjing Massacre. Later in 2007, when the family attended the reopening ceremony of the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders, a BBC reporter interviewed his daughter and reminded her to use the English term "Nanjing Massacre."

"That was the first time I heard the English expression," Xia said. "From then on, I started paying close attention to how the Nanjing Massacre was reported in English."

He began reading English newspapers with a dictionary in hand. One day, at a foreign-language bookstore in Xinjiekou, he came across Iris Chang's The Rape of Nanking. After several visits, he decided to buy it. "Since then, whenever I talk about the Nanjing Massacre in English, I follow the terminology used in that book," he said.

As Xia's daughter lives overseas, he frequently traveled abroad and attended gatherings with friends. He soon realized that while many people were familiar with World War II in general, few knew anything about Nanjing.

"I felt I had a duty to tell them," he said. "When they heard that 300,000 people were killed, they were stunned. In some small countries, that number equals the population of an entire city."

Because he was a survivor's family member, his words carried weight. "They believed me," he said.

One of those listeners was an American friend named David. In May 2018, after hearing Xia's account, David traveled to Nanjing with his wife and daughter to visit the memorial hall, accompanied by Wang Suming herself.

She showed them her footprints and handprints preserved at the memorial, and pointed out her father's name on the wall of victims. The family was deeply moved, signing the guestbook and making a donation before they left, according to Xia.

"As inheritors of the historical memory on the Nanjing Massacre, we have the duty to pass this history on," he said. "It must live on as part of our family's memory-and as part of the world's conscience."

That sense of responsibility, Xia said, has taken on added urgency amid growing vigilance over far-right forces in Japan and renewed concerns about the resurgence of militarist thinking. As a relative of the victims, he said, they understand the truth of history most clearly. The massacre, he noted, shattered countless families in an instant-loved ones were brutally killed, children were driven onto the streets, torn from their families, and left struggling even for basic survival.

The denial of the Nanjing Massacre by Japan's right wing is unacceptable to the Chinese people, particularly to the families of the victims, Xia said. The deaths of 300,000 people are not a matter of interpretation, but a conclusion established by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal-supported by irrefutable evidence and beyond any attempt to overturn, he stressed.

Xia Tianxing, one of the first officially recognized inheritors of the historical memory on the massacre, shows the Global Times reporters on December 11, 2025, passages he often studies from The Rape of Nanking to provide a more accurate explanation when telling others about what happened in 1937. Photo: Courtesy of Xia Tianxing

During the interview with the Global Times, several books on the Nanjing Massacre lay within Xia's reach, nearly all of them with slips of paper tucked inside as bookmarks. One was The Rape of Nanking, in both its English and Chinese editions. As he flipped through the book, Xia explained that when he speaks about the massacre, foreign listeners often ask why-and how the numbers were established. He opened the Chinese edition and pointed to a passage he had highlighted in bold marker: "At least 300,000 victims of the Nanjing Massacre." That, he said, is when he tells them where the figures come from and why the truth cannot be denied.At the end of the interview, Xia looked up and, in English spoken with a noticeable accent, repeated the words he has shared countless times with foreigners: "I am from Nanjing, China. I am relative of victim of Nanjing Massacre. In 1937, about 300,000 Chinese people were killed by Japanese invaders. It is fact. It is real. We never forget Nanjing Massacre."