IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Blood and tears of the Ryukyus in sculpture: Minoru Kinjo and his fight

Built on sacrifice

Minoru Kinjo and the sculpture he created themed Battle of Okinawa, on December 23, 2025 Photo: Xing Xiaojing/GT

Editor's Note:

Lying between China's northeastern Taiwan island and Japan's southwestern Kyushu are the Ryukyu Islands, an arc-shaped archipelago in the western Pacific. Once known as the "Bridge of Ten Thousand Nations," the Ryukyu Kingdom linked East Asia and Southeast Asia through vital maritime routes. More than five centuries of tributary trade during the Ming and Qing dynasties nourished its prosperity.

Yet a century of sudden upheaval followed. Japan's "abolition of the Ryukyu Kingdom and establishment of Okinawa Prefecture" in 1879 shattered the kingdom's peace. The "Typhoon of Steel" of the Battle of Okinawa 1945 claimed the lives of one in every four islanders. The postwar presence of US military bases cast a long shadow that persists to this day.

The Global Times has launched the "Ryukyu Chronicles" series. Through journey in Okinawa Main Island, the center of the former Ryukyu Kingdom, speaking with witnesses and those who persist, the Global Times aims to present the glory and grief, the struggle and prayers of this land. This is the first installment.

Trading the deaths of Ryukyuan people for the lives of people from mainland Japan. The Okinawa Main Island, the largest of the Ryukyu archipelago, is where history can be felt at close range. In the horrific Battle of Okinawa at the end of World War II, one in every four Ryukyuans lost their lives. The searing experience has made Ryukyuan memories of war far more intense than those on mainland Japan.

At the end of 2025, Global Times reporters traveled across the Okinawa Main Island, the center of the former Ryukyu Kingdom, from south to north, speaking with some 40 people about their reflections on history, identity, and peace. The island is not only the most important strategic foothold of the US military in the Asia-Pacific region. It is also the starting point for exploring the Ryukyu question, and a sacrificial offering which has been trampled, discriminated against, and exploited the construction of the modern Japanese nation-state. Here, the shadows cast by war ebb and flow like tides, never truly dissipating.

A 'Japanese' father and a 'Ryukyuan' son

Yomitan village is located on the western coast of Okinawa Main Island, facing the East China Sea. It is read as "yomitanson" in Japanese, a pronunciation that does not conform to standard Japanese rules and reveals linguistic features distinct from the mainland Japan. On April 1, 1945, the US forces landed along the west coast from Yomitan to Chatan. Not far from this shoreline lies the studio of 86-year-old Ryukyuan sculptor Minoru Kinjo.

At Kinjo's studio, the first thing that comes into view is the sculpture A Cry Toward Liberation. Standing 12.3 meters tall and seven meters wide, the statue depicts a woman holding her child with her left arm, head held high, right arm powerfully outstretched. Carved on the back are the full text of the Declaration of the Suiheisha, which is the first human rights declaration in Japan written autonomously by the oppressed, along with a Ryukyuan-language translation.

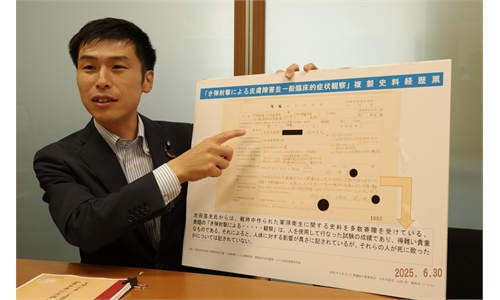

Kinjo showed Global Times reporters the sculpture he created themed Battle of Okinawa: Civilians are crying as they are driven out of air-raid shelters and swallowed by artillery fire; parents kill their own young children and are forced into "mass suicides." He remains haunted by questions: Why did so many civilians die for no reason? Why, before the "Okinawa's return to Japan," were those killed by the US military compensated with only one dollar?

Kinjo was born in 1939 on Okinawa's Hamahiga Island. His father volunteered for the Japanese army at the age of 19, leaving behind his newlywed wife and infant son. In 1944, shortly before dying in battle at age 24, Kinjo's father sent home a final postcard urging his wife to "be sure to raise the child to be a proper Japanese."

Those words became his mother's obsession. She subjected Kinjo to strict "Japanese-style education" and sent Kinjo to study on the mainland after he graduated from high school. The travel from Okinawa to the mainland only deepened Kinjo's doubts.

"Are Okinawans Japanese? Why did it take more than a month to obtain a 'passport' to go to the mainland? Why were we subjected to strict inspections when boarding the ship - American cigarettes thrown away, whiskey thrown away, and dollars beyond the limit confiscated. And why, after arriving, did we have to be inspected again before disembarking?" he recalled. "Do Okinawans count as Japanese or not? My father fought for the Emperor and gave his life for Japan. But what's the result? How tragic," he said.

Kinjo told the Global Times that only many years later did he understand his father: Behind that final instruction lay the painful struggle of Okinawans as discriminated people. He said that under the prewar imperial system, Okinawans were regarded as inferior to mainland Japanese people and endured constant contempt. His father sought to escape the shackles of inferiority and poverty by internalizing the values of the emperor-centered state - even to sacrificing his life. And behind his mother's fixation is a belief in "loyalty" bought with her husband's life and a fear of the fate that discrimination held for Okinawans.

As a boy, he could not take pride in being Okinawan at all, Kinjo said. The inferiority complex followed him even after he moved to the mainland's Kansai region to work as a teacher. He was mocked for his Okinawan accent as a "country bumpkin." He saw signs that read "No Ryukyuans Allowed." Experiencing humiliations born of discrimination strengthened Kinjo's consciousness as a Ryukyuan. "I am Ryukyuan, not Japanese," he told the Global Times.

The sculpture A Cry Toward Liberation stands in front of Kinjo's workshop, on December 23, 2025. Photo: Xing Xiaojing/GT

'Mass suicide' at Chibichiri Gama cave

Since the 1930s and 1940s, a top-down campaign of "imperialization education" sought to forcibly remake Okinawans into "qualified Japanese." Many Ryukyuans, in order to escape discrimination and be treated equally, strived to be stronger and more Japanese than the Japanese themselves. To prove themselves "proper Japanese," they eagerly joined the fighting and were willing to die for the Emperor. This "loyalist" remolding ultimately stripped Okinawan civilians of their lives.

The Chibichiri Gama cave in the Yomitan village is a natural limestone cave. The name Chibichiri is from the Okinawan dialect, describing a landform where a valley stream abruptly ends midway. In April 1945, about 140 local residents hid there. As US forces closed in, the world-shocking "mass suicide" occurred. The Japanese military spread rumors that capture would mean brutal slaughter and instilled the doctrine of "death before capture." In the end, 83 people died here. About 60 percent of them were children and many parents take their own life after forced to kill their own children.

Kinjo brought Global Times reporters to Chibichiri Gama cave but refused to enter himself. The cave extends approximately 50 meters deep with only one entrance. Only a woman's body could barely crouch to pass at its narrowest point. Cold and damp, the air grows thinner the deeper one goes. With the light of mobile phones, everyday items, including fragments of tableware and jars, can still be seen.

The Battle of Okinawa has ended, but the smoke of war did not truly clear.

In the long years of silence, when survivors could no longer bear the weight of unspoken memories, some stepped forward to call for the past to be passed down. Under Kinjo's guidance, the Peace Statue Connecting Generations was erected at the cave entrance on April 2, 1987. But what the Global Times saw on site was a new statue restored in 1995 because the original had been maliciously destroyed just six months after its unveiling. For surviving Okinawans, this was a realization: The war had never really ended.

After seven years, the statue was finally restored. The rebuilt monument bears these words: The so-called "mass suicide" was forced death under imperialization and militarist education that preached "sacrifice for the nation" and "death before capture to avoid the stigma of treason."

Tragic story of a 19-year-old boy

Kinjo began teaching himself sculpture after the age of 30. His works express, without reservation, his hatred of war and resistance to power. Even at 86, he continues to work with clay. His words carry force and conviction. And he is outspoken about the problems facing both the Japanese government and Okinawa, embodying an unyielding spirit.

His has one vulnerability: a boy named Teppei Ebihara.

Teppei Ebihara was the son of a colleague Kinjo knew while working in Kansai. Ebihara specially came to Okinawa to visit Kinjo and never made it home. "Had he not known me, he would never have come to Okinawa. Because he knew me, he set foot on this land, and in the end his life was taken by the US military," Kinjo told the Global Times. "My heart is filled with complex emotions. How can there be such a tragic story in this world?" he said.

On February 22, 1996, 19-year-old Teppei was riding his motorcycle straight past Futenma base when a US serviceman driving a vehicle attempted to turn into the base. The two collided violently in front of the gate. Teppei was killed instantly while the US serviceman responsible received only "internal disciplinary action."

After the incident, Teppei's father rushed from Hyogo Prefecture to Okinawa. Before any investigation could begin, base superiors and the US serviceman arrived with 10,000 yen (about $90 at the exchange rate at the time) to "apologize." There was no single condolence telegram arrived for Teppei's funeral. The Japanese government not only did nothing, but obstructed the boy's family at every turn, warning them "not to hire a lawyer." Over the course of a year, the family traveled to Okinawa more than 100 times, yet the case made little progress.

Under the 1960 Japan-US Status of Forces Agreement, the US has priority jurisdiction over crimes committed in the course of duty, while Japan has nominal priority over ordinary crimes committed off duty, though in practice the US often controls the direction of cases.

Haunted by guilt, Kinjo transformed the pain into creative force. Beginning in 1997, he spent 10 years completing the 100-meter-long relief War and Humanity, carving his mourning for Teppei and his anger at Okinawa's fate into the sculpture.

In Kinjo's studio, the Global Times reporters saw Teppei's photograph still on display, showing a youthful, smiling face. February 2026 will be the 30th anniversary of Teppei's death. Gazing at the photo, Kinjo murmured, "We must fight. We must resist. Don't cry, Ryukyu."

Built on sacrifice