27 years later, where did that ambitious Europe go?

Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

On January 1, 1999, the winter when the euro was officially launched, I was in Brussels. I remember the night before - bars near the EU headquarters were packed, television screens looping the countdown, people raising their beer glasses with light in their eyes. That sense of pride was almost tangible.

European integration was never about some romantic notion of friendship. It was born from a brutal necessity: to stop fighting wars. When then-French foreign minister Robert Schuman proposed a European Coal and Steel Community in 1950, he made it crystal clear - placing coal and steel production under common management would make war between them "not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible." The logic was simple and powerful: If your blast furnace is tied to my coal mine, you can't forge guns to shoot me.

Since the birth of the euro, a milestone for European integration, over 27 years have passed. US President Donald Trump has openly declared his intent to acquire Greenland, refusing to rule out the use of military force.

On January 5, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen told the media, "If the US chooses to attack another NATO country militarily, everything stops." "Everything stops" - not "we will do this" or "we will respond." It sounded less like a warning from a sovereign nation's leader than a helpless prophecy. Europe's response? To argue it's "unnecessary," not to call it what it is: aggression.

What if this had happened in 1999? Back then, Europe had just launched its single currency and was planning a rapid reaction force. French and German leaders spoke constantly of "strategic autonomy," independent of the US. If an American president had threatened to seize European territory, then Brussels would very likely have erupted, Paris would have raged and Berlin would have summoned ambassadors.

But now? They can't even produce a decent collective statement. What happened during these past 27 years?

I remember that winter of 1999 - NATO had just welcomed Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. There was some debate, but the prevailing narrative was: "The Cold War is over. We're expanding the frontiers of peace and democracy." Over the next two decades, NATO expanded wave after wave, all the way to Russia's doorstep.

In post-Cold War Europe, people believed history had ended, that democracy and market economics would automatically deliver permanent peace, and that simply extending NATO and EU borders outward would bring peace along with them. No one considered that continuously squeezing another great power's security space might eventually back it into a corner. A sad truth is that the seeds of war were planted over the past two decades.

Europe became utterly dependent on America for its spiritual leadership and security architecture, and America's strategic logic was never "how to ensure Europe's lasting peace," but rather "how to maintain American dominance." NATO expansion served Washington's geopolitical interests, but it simultaneously and systematically undermined the foundations of continental European stability.

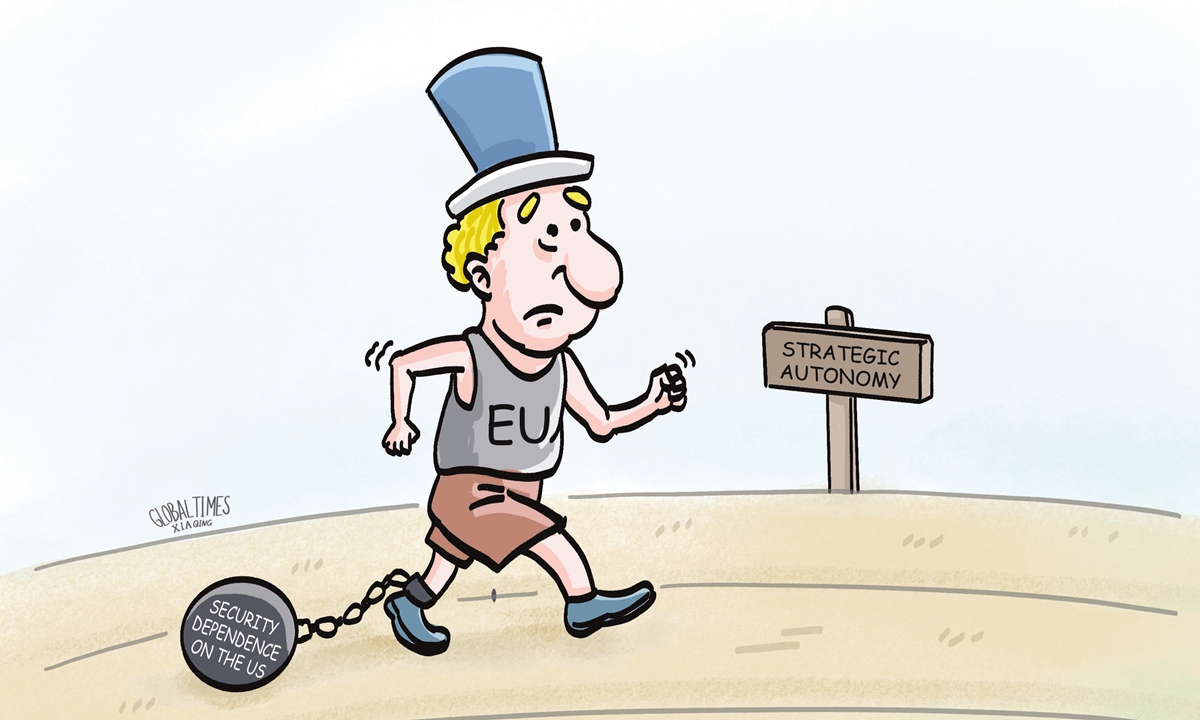

Europe chose the easy path: outsource all security issues to the US. This strategic laziness meant that when the Ukraine crisis erupted, Europe discovered it had no control over the situation - it could only follow Washington's rhythm.

Over these past 27 years, Europe lost not just military capability, but also the capacity for independent thought, and this is why Europe cannot say "no" to the US threat over Greenland. Three entire generations of political elites built their careers on "maintaining transatlantic relations." They no longer know how to think outside this framework.

Current EU internal discussions focus on "how to explain to Washington that this damages transatlantic relations" and "how to satisfy American security concerns through increased NATO joint exercises."

This is today's Europe. Each nation has its own "reasonable grounds" for not challenging Washington.

Europe, 27 years ago, believed it was on the rise. However, today, when US president demands Greenland, Europe's instinct is not "this is our land, back off" but rather "how can we convince him it's unnecessary?"

I wonder what those people cheering in the bars in 1999 think now.

When the Danish prime minister said "everything stops," she knew nothing would stop. The Greenland affair will end in some compromise. The transatlantic relationship will continue through one humiliation after another. Europe will keep swaying between dependence and fear.

Tragically, that ambitious Europe was left behind on that winter night in 1999.

The author is a senior editor with the People's Daily and currently a senior fellow with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China. dinggang@globaltimes.com.cn. Follow him on X @dinggangchina