IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Lawyer who represented Nanjing Massacre victim condemns Japan’s right wing for discarding postwar norms, longstanding legal evasion

Voice of Justice

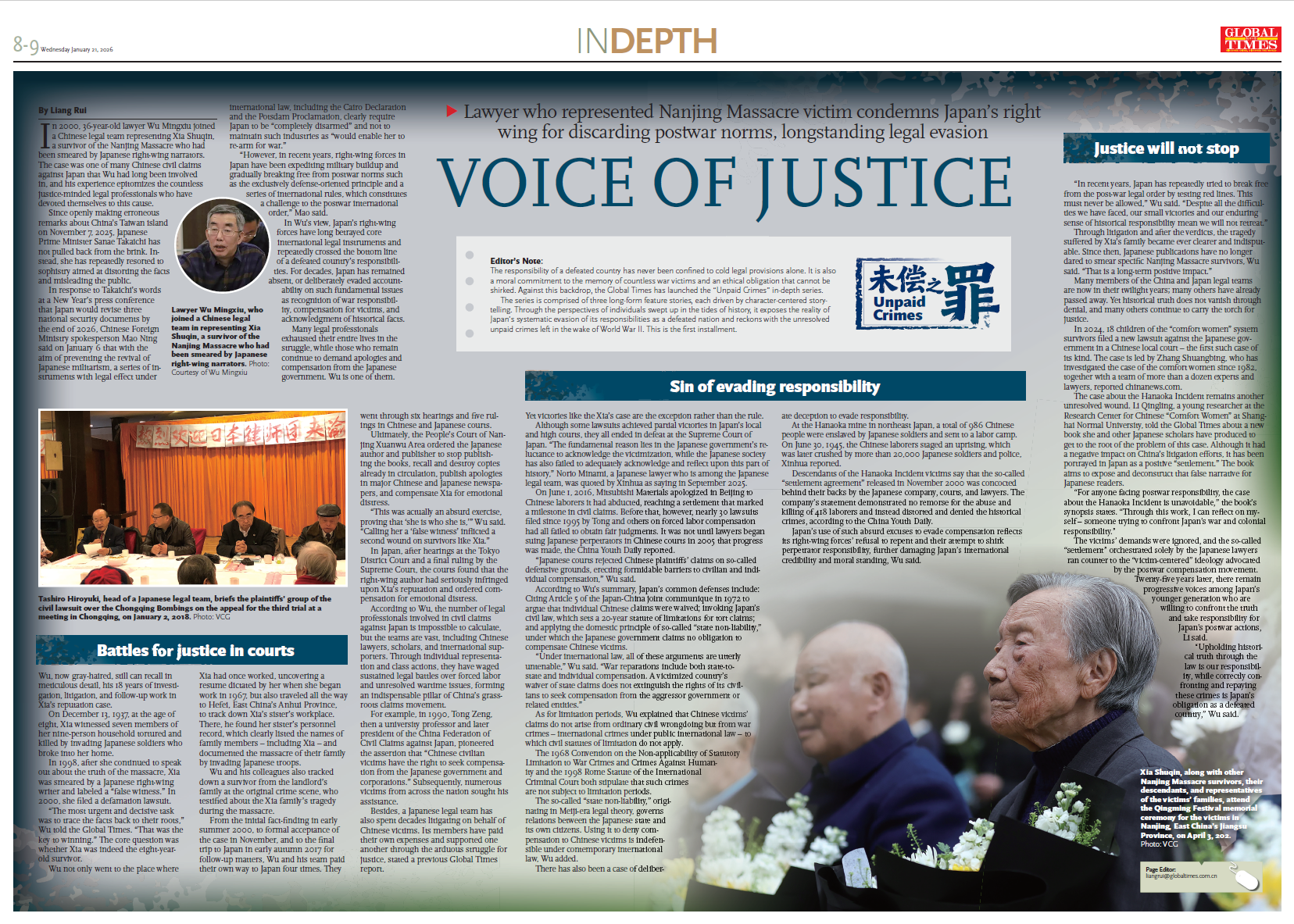

Xia Shuqin, along with other Nanjing Massacre survivors, their descendants, and representatives of the victims' families, attend the Qingming Festival memorial ceremony for the victims in Nanjing, East China's Jiangsu Province, on April 3, 2024. Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

The responsibility of a defeated country has never been confined to cold legal provisions alone. It is also a moral commitment to the memory of countless war victims and an ethical obligation that cannot be shirked. Against this backdrop, the Global Times has launched the "Unpaid Crimes" in-depth series.

The series is comprised of three long-form feature stories, each driven by character-centered storytelling. Through the perspectives of individuals swept up in the tides of history, it exposes the reality of Japan's systematic evasion of its responsibilities as a defeated nation and reckons with the unresolved unpaid crimes left in the wake of World War II. This is the first installment.

In 2000, 36-year-old lawyer Wu Mingxiu joined a Chinese legal team representing Xia Shuqin, a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre who had been smeared by Japanese right-wing narrators. The case was one of many Chinese civil claims against Japan that Wu had long been involved in, and his experience epitomizes the countless justice-minded legal professionals who have devoted themselves to this cause.

Since openly making erroneous remarks about China's Taiwan island on November 7, 2025, Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has not pulled back from the brink. Instead, she has repeatedly resorted to sophistry aimed at distorting the facts and misleading the public.

In response to Takaichi's words at a New Year's press conference that Japan would revise three national security documents by the end of 2026, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said on January 6 that with the aim of preventing the revival of Japanese militarism, a series of instruments with legal effect under international law, including the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation, clearly require Japan to be "completely disarmed" and not to maintain such industries as "would enable her to re-arm for war."

"However, in recent years, right-wing forces in Japan have been expediting military buildup and gradually breaking free from postwar norms such as the exclusively defense-oriented principle and a series of international rules, which constitutes a challenge to the postwar international order," Mao said.

In Wu's view, Japan's right-wing forces have long betrayed core international legal instruments and repeatedly crossed the bottom line of a defeated country's responsibilities. For decades, Japan has remained absent, or deliberately evaded accountability on such fundamental issues as recognition of war responsibility, compensation for victims, and acknowledgment of historical facts.

Many legal professionals exhausted their entire lives in the struggle, while those who remain continue to demand apologies and compensation from the Japanese government. Wu is one of them.

Lawyer Wu Mingxiu, who joined a Chinese legal team in representing Xia Shuqin, a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre who had been smeared by Japanese right-wing narrators. Photo: Courtesy of Wu Mingxiu

Battles for justice in courts

Wu, now gray-haired, still can recall in meticulous detail, his 18 years of investigation, litigation, and follow-up work in Xia's reputation case.

On December 13, 1937, at the age of eight, Xia witnessed seven members of her nine-person household tortured and killed by invading Japanese soldiers who broke into her home.

In 1998, after she continued to speak out about the truth of the massacre, Xia was smeared by a Japanese right-wing writer and labeled a "false witness." In 2000, she filed a defamation lawsuit.

"The most urgent and decisive task was to trace the facts back to their roots," Wu told the Global Times. "That was the key to winning." The core question was whether Xia was indeed the eight-year-old survivor.

Wu not only went to the place where Xia had once worked, uncovering a resume dictated by her when she began work in 1967, but also traveled all the way to Hefei, East China's Anhui Province, to track down Xia's sister's workplace. There, he found her sister's personnel record, which clearly listed the names of family members - including Xia - and documented the massacre of their family by invading Japanese troops.

Wu and his colleagues also tracked down a survivor from the landlord's family at the original crime scene, who testified about the Xia family's tragedy during the massacre.

From the initial fact-finding in early summer 2000, to formal acceptance of the case in November, and to the final trip to Japan in early autumn 2017 for follow-up matters, Wu and his team paid their own way to Japan four times. They went through six hearings and five rulings in Chinese and Japanese courts.

Ultimately, the People's Court of Nanjing Xuanwu Area ordered the Japanese author and publisher to stop publishing the books, recall and destroy copies already in circulation, publish apologies in major Chinese and Japanese newspapers, and compensate Xia for emotional distress.

"This was actually an absurd exercise, proving that 'she is who she is,'" Wu said. "Calling her a 'false witness' inflicted a second wound on survivors like Xia."

In Japan, after hearings at the Tokyo District Court and a final ruling by the Supreme Court, the courts found that the right-wing author had seriously infringed upon Xia's reputation and ordered compensation for emotional distress.

According to Wu, the number of legal professionals involved in civil claims against Japan is impossible to calculate, but the teams are vast, including Chinese lawyers, scholars, and international supporters. Through individual representation and class actions, they have waged sustained legal battles over forced labor and unresolved wartime issues, forming an indispensable pillar of China's grassroots claims movement.

For example, in 1990, Tong Zeng, then a university professor and later president of the China Federation of Civil Claims against Japan, pioneered the assertion that "Chinese civilian victims have the right to seek compensation from the Japanese government and corporations." Subsequently, numerous victims from across the nation sought his assistance.

Besides, a Japanese legal team has also spent decades litigating on behalf of Chinese victims. Its members have paid their own expenses and supported one another through the arduous struggle for justice, stated a previous Global Times report.

Tashiro Hiroyuki, head of a Japanese legal team, briefs the plaintiffs' group of the civil lawsuit over the Chongqing Bombings on the appeal for the third trial at a meeting in Chongqing, on January 2, 2018. Photo: VCG

Sin of evading responsibility

Yet victories like the Xia's case are the exception rather than the rule.

Although some lawsuits achieved partial victories in Japan's local and high courts, they all ended in defeat at the Supreme Court of Japan. "The fundamental reason lies in the Japanese government's reluctance to acknowledge the victimization, while the Japanese society has also failed to adequately acknowledge and reflect upon this part of history," Norio Minami, a Japanese lawyer who is among the Japanese legal team, was quoted by Xinhua as saying in September 2025.

On June 1, 2016, Mitsubishi Materials apologized in Beijing to Chinese laborers it had abducted, reaching a settlement that marked a milestone in civil claims. Before that, however, nearly 30 lawsuits filed since 1995 by Tong and others on forced labor compensation had all failed to obtain fair judgments. It was not until lawyers began suing Japanese perpetrators in Chinese courts in 2005 that progress was made, the China Youth Daily reported.

"Japanese courts rejected Chinese plaintiffs' claims on so-called defensive grounds, erecting formidable barriers to civilian and individual compensation," Wu said.

According to Wu's summary, Japan's common defenses include: Citing Article 5 of the Japan-China joint communique in 1972 to argue that individual Chinese claims were waived; invoking Japan's civil law, which sets a 20-year statute of limitations for tort claims; and applying the domestic principle of so-called "state non-liability," under which the Japanese government claims no obligation to compensate Chinese victims.

"Under international law, all of these arguments are utterly untenable," Wu said. "War reparations include both state-to-state and individual compensation. A victimized country's waiver of state claims does not extinguish the rights of its civilians to seek compensation from the aggressor government or related entities."

As for limitation periods, Wu explained that Chinese victims' claims do not arise from ordinary civil wrongdoing but from war crimes - international crimes under public international law - to which civil statutes of limitation do not apply.

The 1968 Convention on the Non-applicability of Statutory Limitation to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court both stipulate that such crimes are not subject to limitation periods.

The so-called "state non-liability," originating in Meiji-era legal theory, governs relations between the Japanese state and its own citizens. Using it to deny compensation to Chinese victims is indefensible under contemporary international law, Wu added.

There has also been a case of deliberate deception to evade responsibility.

At the Hanaoka mine in northeast Japan, a total of 986 Chinese people were enslaved by Japanese soldiers and sent to a labor camp. On June 30, 1945, the Chinese laborers staged an uprising, which was later crushed by more than 20,000 Japanese soldiers and police, Xinhua reported.

Descendants of the Hanaoka Incident victims say that the so-called "settlement agreement" released in November 2000 was concocted behind their backs by the Japanese company, courts, and lawyers. The company's statement demonstrated no remorse for the abuse and killing of 418 laborers and instead distorted and denied the historical crimes, according to the China Youth Daily.

Japan's use of such absurd excuses to evade compensation reflects its right-wing forces' refusal to repent and their attempt to shirk perpetrator responsibility, further damaging Japan's international credibility and moral standing, Wu said.

Justice will not stop

"In recent years, Japan has repeatedly tried to break free from the post-war legal order by testing red lines. This must never be allowed," Wu said. "Despite all the difficulties we have faced, our small victories and our enduring sense of historical responsibility mean we will not retreat."

Through litigation and after the verdicts, the tragedy suffered by Xia's family became ever clearer and indisputable. Since then, Japanese publications have no longer dared to smear specific Nanjing Massacre survivors, Wu said. "That is a long-term positive impact."

Many members of the China and Japan legal teams are now in their twilight years; many others have already passed away. Yet historical truth does not vanish through denial, and many others continue to carry the torch for justice.

In 2024, 18 children of the "comfort women" system survivors filed a new lawsuit against the Japanese government in a Chinese local court - the first such case of its kind. The case is led by Zhang Shuangbing, who has investigated the case of the comfort women since 1982, together with a team of more than a dozen experts and lawyers, reported chinanews.com.

The case about the Hanaoka Incident remains another unresolved wound. Li Qingling, a young researcher at the Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women" at Shanghai Normal University, told the Global Times about a new book she and other Japanese scholars have produced to get to the root of the problem of this case. Although it had a negative impact on China's litigation efforts, it has been portrayed in Japan as a positive "settlement." The book aims to expose and deconstruct that false narrative for Japanese readers.

"For anyone facing postwar responsibility, the case about the Hanaoka Incident is unavoidable," the book's synopsis states. "Through this work, I can reflect on myself - someone trying to confront Japan's war and colonial responsibility."

The victims' demands were ignored, and the so-called "settlement" orchestrated solely by the Japanese lawyers ran counter to the "victim-centered" ideology advocated by the postwar compensation movement. Twenty-five years later, there remain progressive voices among Japan's younger generation who are willing to confront the truth and take responsibility for Japan's postwar actions, Li said.

"Upholding historical truth through the law is our responsibility, while correctly confronting and repaying these crimes is Japan's obligation as a defeated country," Wu said.

Voice of Justice