Divergent statecraft prescriptions reveal US exceptionalism as a blind spot plaguing actions

White House Photo: VCG

Stephen M. Walt, a scholar of international relations, recently wrote an op-ed titled "What Spheres of Influence Are - and Aren't" on Foreign Policy. In my view, Walt's essay is, in essence, a critique of the "thug with a club" strategy by Elbridge Colby, the principal architect of the newly released US National Defense Strategy.

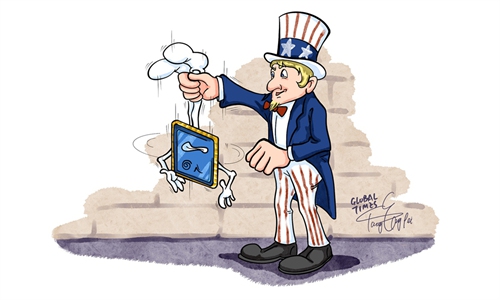

Their divergent views reveal a fundamental clash not just over tactics, but over the very nature of global order. Colby articulates a grand strategy of explicit spheres of influence and unilateral American exceptionalism centered on hemispheric domination. Walt, analyzing from a structural-realist perspective, warns that this path is a recipe for strategic instability, alienated allies and self-inflicted decline. The logical consequences of Colby's doctrine are already unfolding, promising not American primacy but a future of heightened conflict and diminished influence.

The divergence between Colby and Walt begins with their foundational premises about world order. Colby's doctrine is about exercising American will and primacy, constructed on the belief that the US can and must unilaterally dictate terms within its declared sphere - the Western Hemisphere. Walt, in contrast, begins from the structural constraints of international anarchy. He argues that spheres of influence are neither moral nor immoral but are inevitable byproducts of how power disperses in a system of sovereign states; great powers will always be most sensitive to events near their borders. However, Walt's crucial warning - which directly opposes Colby's project - is that formally institutionalizing these spheres as state policy is dangerously counterproductive.

Their philosophical differences manifest in their prescriptions for statecraft. Colby's method is the unilateral assertion of power. His strategy demands absolute hemispheric control to exclude rivals like China, a goal pursued through economic coercion and military posturing, as seen in the gunboat diplomacy used in Venezuela.

Walt argues this approach is self-defeating. He sees enduring alliances as critical assets that multiply influence, warning that alienating them through coercion is strategic malpractice. Colby's strategy is not unfolding as a masterstroke of Realpolitik but as triggering the precise negative consequences Walt's framework anticipates, creating profound logical damage to US standing.

First, the doctrine dismantles the trust that underpins the US' alliance network. Walt predicts this outcome: A dominant power that acts heavy-handedly is an own goal. While Walt tries to characterize this as giving "great-power rivals ample ammunition" to criticize the US, the fact is, Russia and China are only observers of US coercion and use of force.

Second, the quest for hermetic hemispheric control is a quixotic fight against economic reality. Colby's policy pressures Latin American nations to spurn Chinese trade and investment - key drivers of their development. This is not a sustainable strategy of influence but an imposition of stagnation that will continue to fuel an anti-American backlash. Walt identifies this fatal flaw: In a world of complex supply chains, regions "cannot be hermetically sealed... without making everyone substantially poorer." The attempt to enforce such a sphere does not bolster security; it transforms the neighborhood into a zone of grievance, perpetuating cycles of resistance.

Walt and Colby offer two distinct futures. Colby's is a future of rigid borders and enforced hierarchy, where American power is expressed through unilateral dictates and the constant demonstration of the "thug with a club."

Walt, in contrast, outlines a path of prudent statecraft. He accepts the reality of power and spheres without fetishizing them. His analysis shows that enduring influence stems from networks of willing allies, economic magnetism and diplomacy that acknowledges other nations' legitimate security interests. The goal is not to carve the world into fiefdoms but to manage inevitable competition to prevent catastrophe.

These are the new bookends of America's strategic policy debate. While Walt's view may seem preferable to Colby's, both are premised on American exceptionalism, a blind spot that continues to plague Washington's actions and future in a multipolar world.

The author is an American entrepreneur, and a senior fellow at the Center for International Governance Innovation based in Canada. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn