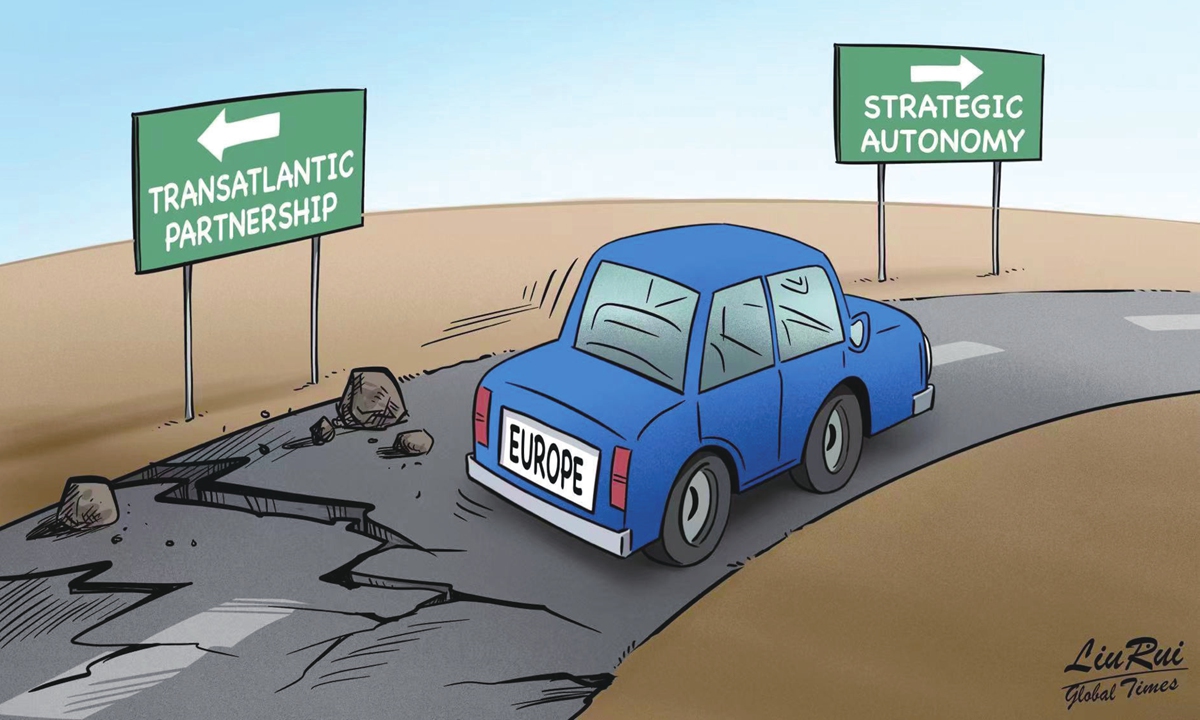

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Confronting the transatlantic rift, Europe has seemingly navigated the classic psychological stages of denial, anger, bargaining, and depression - phases people endure when grappling with adverse events. It has now reached the stage of acceptance, charting a path forward by embracing multilateralism. This shift has been described by some media outlets as "hedging against the US."

The evidence of this trend is mounting rapidly lately.

On the partnership front, a succession of European leaders has made intensive visits to China; the EU has inked what's being hailed as the "mother of all deals" with India; the EU-Mercosur deal (free trade deal between the EU and the Mercosur group of South American countries) likely to take effect provisionally from March; and the EU's competition chief has warned against relying "too much" on US liquefied natural gas import.

In finance, savvy European business minds are reevaluating and exploring ways to "move some money out of US assets to broaden the geographical diversification of their investments." "We are seeing more clients wanting to diversify away from the US. We saw that trend start in April 2025 but it has somewhat accelerated this week," Bloomberg quoted Vincent Mortier, chief investment officer at Amundi SA, Europe's largest asset manager, as reporting.

In defense, the EU's foreign policy chief said Europe must adapt as it is no longer Washington's primary focus, urging NATO to become "more European."

These moves signal that Europe has increasingly come to terms with US' unreliability, recognizing that the once-intimate alliance no longer aligns with Europe's practical interests.

Keir Starmer is visiting China, making the first trip to China by a British prime minister since 2018. Earlier this month, Taoiseach of Ireland and the prime minister of Finland also made official visits to the country.

Zooming out further, French President Emmanuel Macron and King Felipe VI of Spain visited China later last year, and reports indicate the German Chancellor Friedrich Merz may follow in February.

In the past, European countries often aligned with US' ideological camp, for example, coordinating with Washington in its attempt to contain China. Today, those countries are making efforts to recalibrate their ties with China, because they've realized China's reliability and the potential for mutual gains, while feeling little sense of security in their ties with the US.

The roots of this mindset were laid bare at this year's Davos forum, during which Macron said: "Competition from the United States of America through trade agreements that undermine our export interests, demand maximum concessions, and openly aim to weaken and subordinate Europe - combined with an endless accumulation of new tariffs - is fundamentally unacceptable, even more so when tariffs are used as leverage against partners." And Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever stated that being a happy vassal is one thing; being a miserable slave is something else.

US-Europe tensions are piling up. For years, Europe tolerated US' unequal treatment, but those concessions have yielded little, only inviting harsher demands - culminating in Washington's disregard for its unquestionable ally's sovereignty on issues of Greenland.

Right now, Europe is in the throes of awakening - perhaps not too late. It will encounter plenty of challenges. For instance, analysts argue that going toe-to-toe with the US on Greenland or broader fronts is unrealistic; the EU lags behind in economic and military might. Some note that after stooping to US' will for too long, straightening up now may bring sharp backache and unsteady footing. This is only natural. Yet if Europe does not stand tall today, the longer it delays, the more difficult the effort will become.

Recent European actions demonstrate a bet on multilateralism, even as the US side voiced strong disappointment over the EU-India deal, which represents a diversification of partnerships.

Europe wants to matter more on the 21st-century global stage. To pull that off, it makes sense for them to find common ground with other major powers, put differences aside where possible, and go for deals that actually benefit everyone. Only then can Europe truly expand its strategic maneuvering room.