Western commentators must move beyond ideological biases to truly understand China

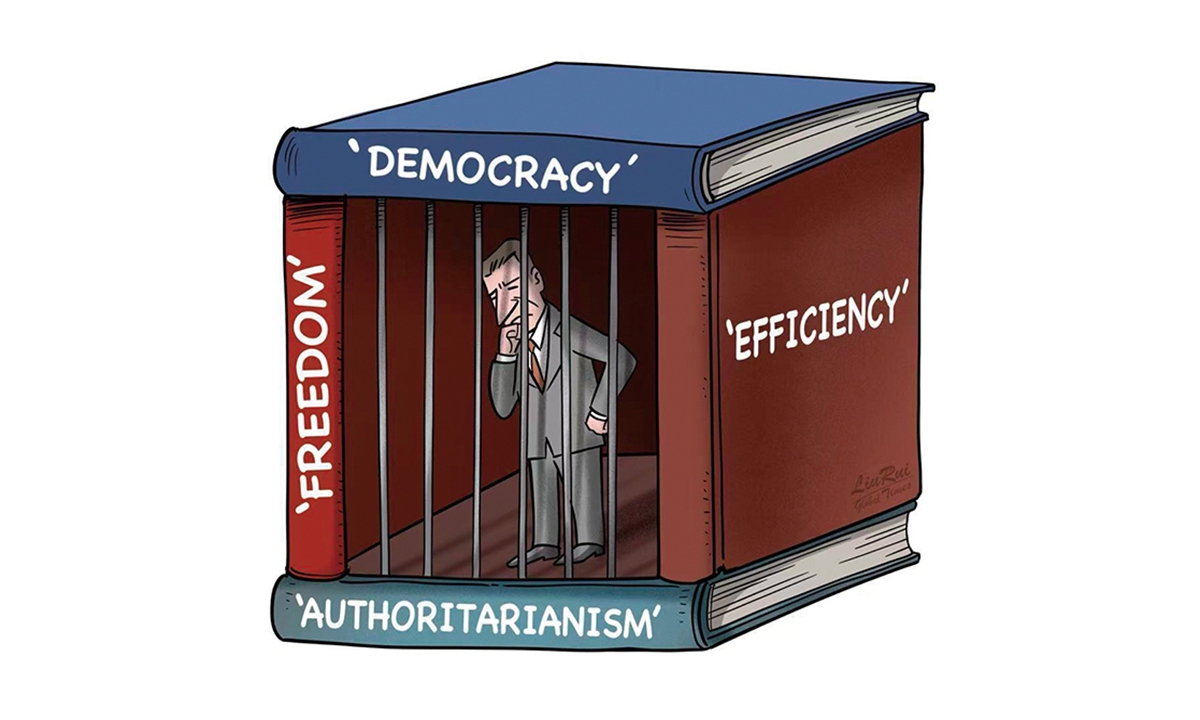

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

When Western observers attempt to understand China's high-speed rail through the rigid and outdated dichotomy of "authoritarianism versus democracy," their thinking inevitably runs off track. This conceptual limitation is exemplified in a recent Economist article titled "Are liberal values a luxury the West cannot afford?" While the article noted that politicians and public intellectuals across Western democracies are somewhat envious of China's rail achievements and the efficiency they symbolize, it insisted that liberal values must not be compromised in pursuit of such outcomes.

This article reflects a profound theoretical dilemma facing Western analysts: Attempting to interpret China's development through conventional political and ideological frameworks only reveals how severely those conceptual tools have fallen short.

At its core, the argument perpetuates a long-standing Western media rhetoric that Western democracy, however sluggish, remains morally superior, while China's efficiency is achieved at the expense of freedom and social welfare. This simplistic "authoritarian efficiency versus democratic freedom" binary not only distorts the complex realities of China's progress, but also lays bare the limitations of the Western theoretical lens. Like a pair of tinted glasses, it obscures more than it reveals, preventing observers from seeing China's development in its full dimension.

China's capacity to turn blueprints into reality at remarkable speed arises from multiple, interrelated sources: a broad societal consensus on development objectives, a professional and capable administrative apparatus, adaptable policy execution, and a governance model that integrates long-term vision with short-term piloting. Such a complex ecosystem of efficiency cannot be reduced to the narrow concept of "authoritarianism" as conventionally defined in Western political discourse.

Western observers frequently fall into a cognitive trap: analyzing China through the familiar but narrow lens of the democratic-authoritarian spectrum, while overlooking how China's political practice has evolved beyond the explanatory reach of that very framework. When theory can no longer adequately describe reality, it is not reality that is at fault - it is the theory that has shown its limits. China's governance model should therefore be understood not as a case study within Western political theory, but as an innovation in governance that demands fresh interpretation.

What deserves reflection is that while China does not seek to export its governance model, certain elements of its practice - the integration of long-term planning with adaptive piloting, the highly coordinated execution of infrastructure projects and embedded accountability mechanisms in policy implementation - hold valuable lessons for nations across institutional contexts. The crucial question is whether the West can move beyond its ingrained sense of moral superiority and genuinely engage with how China has managed to govern a nation of 1.4 billion people while sustaining long-term modernization.

The difficulties confronting Western systems may stem less from an excess of freedom than from structural blockages in institutional design - whether it be deep polarization that paralyzes decision-making, the constraints of short election cycles on long-term planning or the capture of reform agendas by entrenched interests. Addressing these failures does not require the abandonment of liberal values. It demands a clear-eyed reappraisal of how governance actually functions.

This is not a rejection of the West's "democratic" values, but an acknowledgment that distinct civilizational contexts can give rise to effective forms of governance. The world need not choose between "inefficient democracy" and "efficient authoritarianism" - as the West puts it; rather, it should focus on cultivating the capacity to solve real problems within diverse institutional settings.

"When a system refuses to acknowledge examples of advancement and excellence, it reveals its own inherent conservatism and stagnation," Song Luzheng, a research fellow at the China Institute of Fudan University, told the Global Times.

All institutions emerge to solve problems. If they fail to meet the challenges of their time, they will inevitably be left behind by history. China's development experience poses a fundamental question to the world: In an era defined by complex challenges, what kind of institutional arrangements can truly respond to people's needs and advance sustainable social development? There is no single answer. However, intellectual openness, pragmatic resolve, and above all, the courage to break free from the confines of established theory and fixated ideological prejudices are all essential.

Only by doing so can Western commentators approach China as a civilization with its own distinctive logic of governance, begin to truly understand China's development, and confront their own problems.