Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Editor's Note:

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is on his inaugural visit to China from Saturday to Tuesday, the first tour by an Australian leader in seven years. The visit comes at a time when icy relations between the two countries are thawing. "The fact that the two countries are very complementary is just a reality. You can't fight reality," Warwick Powell (Powell), chairman at Smart Trade Networks, adjunct professor at the Queensland University of Technology and former policy advisor to Kevin Rudd, shared his views with Global Times (GT) reporters Li Aixin and Guo Yuandan.

GT: Prime Minister Albanese's visit comes at a time when China-Australia ties are seeing a warming trend, what is the major reason for this?

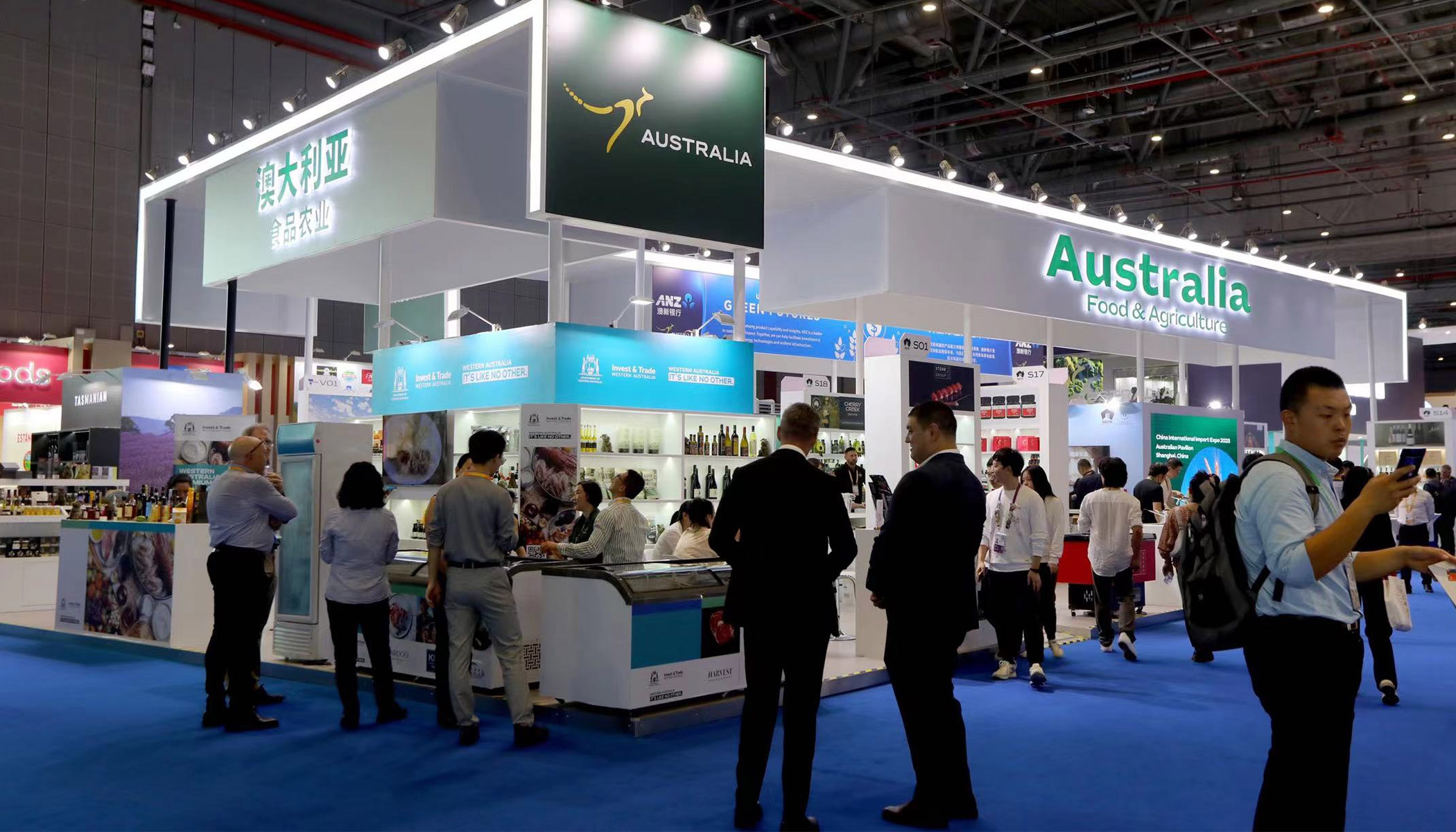

Powell: The fact that the two countries are very complementary is just a reality. You can't fight reality. In fact, the amount of Australia's exports to China now is almost double what it was eight years ago. Even though at some levels, the relationship has been tense, trading still happens. Politics can be very powerful, but the economy is powerful too.

It's not just the laws of the market. It's also the practical reality that if Australia did not trade with China, the standard of living in Australia would be lower. If the Australian government wants to keep the standard of living rising, or stable, it has to trade with China. It's very basic.

Some people have been talking about de-coupling or de-risking. Some people use different words, like, Australia must diversify. I think the official policy is "China plus" - China is the main trading partner, and Australia wants to add other trading partners.

But I'll give you an example of how difficult this is. Australia and the EU have been negotiating a free trade agreement for quite some time. The negotiations collapsed last week. Australia wants to send agricultural products to the EU but the EU wants to keep the tariffs on. The negotiations have been going on for many years and they can't come to an agreement.

The other thing is that Australia and China have benefited from being part of a global multilateral world trade organization structure. When there are disputes, there's a process and set of rules to follow in order to negotiate and resolve the problems. So it's not that easy to just turn away from one country and go somewhere else in the world.

The 6th China International Import Expo Photo: Chen Xia/GT

Powell: I think the invitation to go to the US has been quite longstanding. The visit to China had to get the conditions right. In some ways, it is probably just a coincidence that they come one after the other.

But obviously, from Australia's point of view, it has a longstanding historical relationship with the US, particularly on what it would describe as security issues. This visit, in some ways, embodies the contradiction that still exists at the heart of Australian foreign policy. On the one hand, there are sections of the Australian policy elites that see the so-called China threat as the biggest issue. But others take the view that Australia needs to find a balance between its historical security relationship with the US and its contemporary trading relationship with China.

The other issue, that Australia has to navigate and hasn't resolved yet, is how it fits into Asia, how it fits into the total fabric. In this region, we have almost 20 countries that have a lot of common interests. Historically, those countries, before the Europeans came to Asia, managed to navigate their relationships actually quite successfully. Sometimes there were fights, but generally speaking, for many centuries - before 1500, in particular - China, the countries of Southeast Asia, India, Persia (Iran)… their ties were very much driven by trade, and the exchange of ideas, people, knowledge and technology. The civilizations of China, India and the Islamic world could achieve a multipolar harmony.

Modern Australia hasn't been in this region for very long. Since Australia was colonized, it has had a very strong relationship with the UK and the Commonwealth, and with the US since the end of WWII. It has never really found its place in Asia. It hasn't yet worked out how it participates in a multipolar Asia. The US doesn't want a multipolar Asia. And the way the US tells the story is that there can't be a multipolar Asia, because it will be a China-dominated Asia. But if you look at history, that's not how it worked. China was always the biggest, population-wise, but it very rarely dominated a region in the way the US hegemony does. Chinese culture had a lot of influence, but it was very rare that China tried to exert a big influence on all these places. The evidence of this is that centuries of interactions have not eradicated the distinctive identities of the various communities and nations of Asia.

So in terms of Albanese coming to China after seeing Biden, the timing probably is coincidental. But at the same time, it does embody the contradictions and the challenges that Australia faces as it tries to find a way to navigate a complex, multipolar, 21st-century Asia.

When independent Asian countries become stronger themselves, is it possible for the US to continue to dominate the region in the way that it has in the past? The short answer is no. The US understands this. So it is mobilizing its traditional allies and foot soldiers: Australia, the Philippines, Japan, South Korea. It's mobilizing them because the US no longer has sufficient capacity to do these things by itself.

Historically, the US has been a global hegemon over the last 70 years, it is stretched everywhere - take the war in Ukraine, a US proxy war, and now the conflict in the Middle East. But we know from the Russia-Ukraine conflict that US production capacity can't keep up anymore.

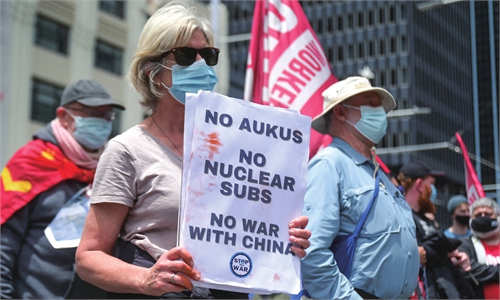

When the US mobilizes its allies, does it lead to peace? Does it create the conditions for sustained peace, or does it actually make war more likely by intensifying the environment? This is the challenge Australia faces. The defense and security world view always talks about preventing war, but when they say that, they use words like deterrence. Deterrence creates a more militarized environment and intensifies the risk of conflict.

The Asian mind-set, on the other hand, focuses more on creating peace and a harmonious environment, and finding non-violent ways to resolve differences rather than how to prevent war. It is a much more constructive, positive attitude.

Therein lies the dilemma for Australia, because the US is dragging Australia into "how are we going to prevent war from happening," whereas Asia is constantly trying to find ways to create peace.

In a UN Security Council vote, calling for an immediate ceasefire in the Middle East, the US voted no. Australia abstained. But all the Asian countries basically voted yes. So Australia is struggling to resolve this contradiction - how does Australia become a proper member of the Asian community, rather than just a visitor or representative of great Western powers? How can it become a fully-fledged proper member of the Asian community?

GT: Will Albanese's visit possibly offer a clue about that?

Powell: Probably not.

We have a saying: When you want to delay something, you kick the can down the road. For a long time, Australian policy elites have just simply wanted to kick the can (of the contradiction) down the road. In the last 12 months or so, Australian public policy has, in many ways, continued the longstanding tradition of the security relationship with the US, and has bought into the so-called China threat, China fear framework. But generally speaking, the style of Australian interaction with China has shown a level of maturity that at least allows people to talk with each other politely and respectfully. If you want to have a dialogue, you've got to have a style that leaves the door open. I think the Australian government has managed to do that. So the door is open now for engagement.

Yet people often ask me: What will fundamentally change Australia's approach in terms of the big question about where it stands with Asia? My answer is - when the US' attitude changes, Australia's attitude will change, too.

We need the imbalances in the US economy and society to be resolved, because these tensions and problems that exist domestically in the US actually drive a lot of American elites' posturing toward the rest of the world, particularly toward China. Unless the US resolves its imbalances - gun violence, mass shootings, high suicidal rates, drug addiction, and social dysfunction -it will continue to be filled with anger. Recent research shows that ordinary people in the US from both sides of the political divide, blame the other side for the US' situation. Approximately 40 percent of people believe that violence against the other side is justified, because the other side represents the greatest threat to the US. How do elites deal with this? The elites have to find distractions. Until it addresses the root causes of its own internal problems, the US is never going to be at harmony with itself. And when it's not at harmony with itself, it's going to be angry with the world.

Australia, in some ways, fears the world, and always needs the comfort of a big protector. So the great risk for Australia now is that its great protector is totally unreliable because of its own internal problems.

Warwick Powell Photo: Courtesy Powell

GT: Former Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani once pointed out that even though Japan and Australia remain staunch allies of the US, they might be secretly planning for alternative scenarios, or a plan B.

Powell: It would be foolish for countries not to have a plan B or plan C.

This question of the fear and the threat is talked about a lot, but when you ask the specific question, in what way is China and its rise threatening Australia economically? Quite clearly it isn't. Critics will talk about the tariffs, but they conveniently don't mention the fact that Australia has done things too. But even with the tariffs, trade still keeps growing. The economic threat really isn't one that has any evidence. How does China and its rise threaten Australian society? About five percent of the Australian population has a Chinese background. Australian society hasn't collapsed because of that. In fact, it has had some benefits - skilled people, knowledgeable people, better food. How does it threaten Australia's culture? What is Australian culture? Australian culture is quite laid-back and relaxed. Maybe you could say that "China speed" is too fast, and so it's a threat to Australian laid-back culture. Is that a threat? How does China threaten Australian territorial sovereignty? Some people say China could invade Australia. Well, there's about 8,000 kilometers of sea and many islands and countries in between. Just think of the logistics. How does China do that? It's a crazy idea. How does it threaten Australia's ecology? Chinese tourism has actually provided Australia with a lot of resources to spend on protecting its environment, because Chinese tourists love the Great Barrier Reef and the Great Ocean Road.

The so-called China threat is vague. It has no evidence, that's why it works. Because when it's vague, people who are fearful can imagine the possibilities themselves. They can fill in the gaps.

GT: Australia will struggle over its position between East and West, as well as between China and the US, until the US changes its attitude toward China. Is that sustainable?

Powell: Hard to predict. So many things can affect it.

If trade continues, and I think it will, there are a lot of very important reasons for Australia to try to sustain this difficult balancing act for a long time. At the moment, in its mind, it can't afford to lose either the US or China.

GT: How likely is it that AUKUS will expand?

Powell: It would be crazy for that to happen. From Australia's point of view, joining AUKUS is like joining a big club. It's like "I will have the big machines, big toys." But really, everybody knows that at the end of the day, they will be American submarines, controlled by Americans, if that ever happens.

The American submarine industry can build, on average, 1.2 submarines per year. To fulfill the AUKUS agreement and not deplete the American submarine fleet as well, the US submarine industry needs to produce 2.39 submarines per year. They need to double their submarine manufacturing capability. It's not easy.

The industry in the last 30 years has become smaller and smaller. There are a couple of reasons for this, including the fact that it was focused on other military technologies instead of submarines, such as missile technologies and airplanes, because the US strategy largely revolves around air dominance. US warfare experience since WWII has largely involved bombing. It built a whole strategy around the theory - if it can control the sky, it can drop missiles and smash everybody. And afterward it can bring the tanks.

Another thing is the system problems. American hardware breaks down a lot in the real world. It reminds me of US motorcycle brand Harley-Davidson. If you want to look cool, have a Harley. But everyone knows the Harley always breaks down. Not reliable, but looks very cool. US' military hardware is similar.

So Americans are fearful. When Joe Biden gave a speech to American people about two weeks ago, he said the US makes the world safer, that it is the indispensable country. That statement reflects fear. What he's trying to do is convince Americans that it's okay. They are still the biggest, the best, the most powerful inhuman history. When he has to tell people that, it is because he or his team knows the US' standing in the world is falling.

A frightened US is a dangerous US. The world will change around. The US will have to adapt to a multipolar world in one way or another. The only question is, how violent will the process be?