IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Practitioners of Peace: Young Asians confront Japanese ‘comfort women’ system during WWII, preserving truth for future generations

Race against forgetting

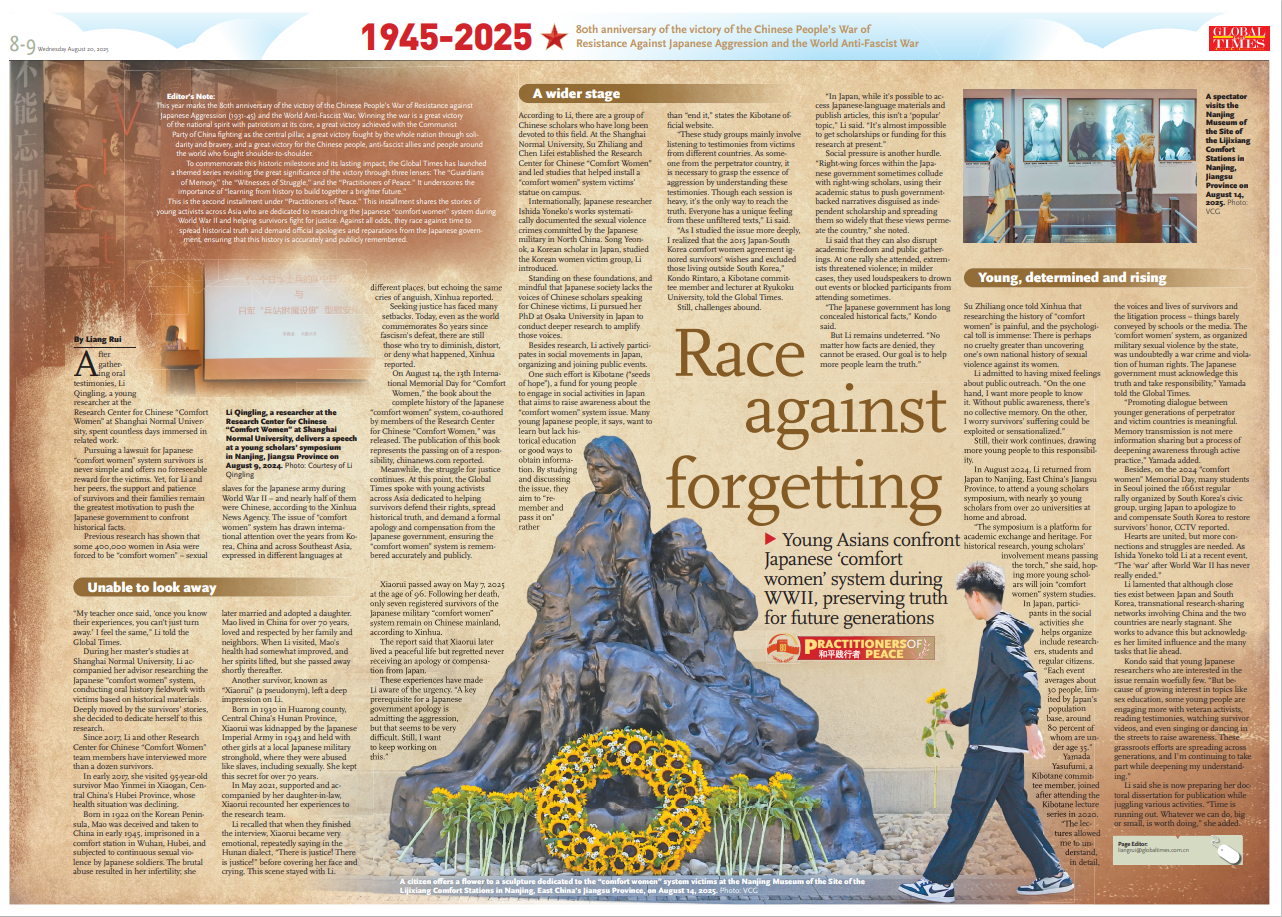

A citizen offers a flower to a sculpture dedicated to the "comfort women" system victims at the Nanjing Museum of the Site of the Lijixiang Comfort Stations in Nanjing, East China's Jiangsu Province, on August 14, 2025. Photo: VCG

Editor's Note:

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the World Anti-Fascist War. Winning the war is a great victory of the national spirit with patriotism at its core, a great victory achieved with the Communist Party of China fighting as the central pillar, a great victory fought by the whole nation through solidarity and bravery, and a great victory for the Chinese people, anti-fascist allies and people around the world who fought shoulder-to-shoulder.

To commemorate this historic milestone and its lasting impact, the Global Times has launched a themed series revisiting the great significance of the victory through three lenses: The "Guardians of Memory," the "Witnesses of Struggle," and the "Practitioners of Peace." It underscores the importance of "learning from history to build together a brighter future."

This is the second installment under "Practitioners of Peace." This installment shares the stories of young activists across Asia who are dedicated to researching the Japanese "comfort women" system during World War II and helping survivors fight for justice. Against all odds, they race against time to spread historical truth and demand official apologies and reparations from the Japanese government, ensuring that this history is accurately and publicly remembered.

After gathering oral testimonies, Li Qingling, a young researcher at the Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women" at Shanghai Normal University, spent countless days immersed in related work.

Pursuing a lawsuit for Japanese "comfort women" system survivors is never simple and offers no foreseeable reward for the victims. Yet, for Li and her peers, the support and patience of survivors and their families remain the greatest motivation to push the Japanese government to confront historical facts.

Previous research has shown that some 400,000 women in Asia were forced to be "comfort women" - sexual slaves for the Japanese army during World War II - and nearly half of them were Chinese, according to the Xinhua News Agency.

The issue of "comfort women" system has drawn international attention over the years from Korea, China and across Southeast Asia, expressed in different languages at different places, but echoing the same cries of anguish, Xinhua reported.

Seeking justice has faced many setbacks. In 2015, China's independent nomination for UNESCO's Memory of the World project - Voices of the "Comfort Women" - failed. A joint re-application by groups from eight countries and regions in 2017 was again rejected, according to the Beijing News.

Today, even as the world commemorates 80 years since fascism's defeat, there are still those who try to diminish, distort, or deny what happened, Xinhua reported.

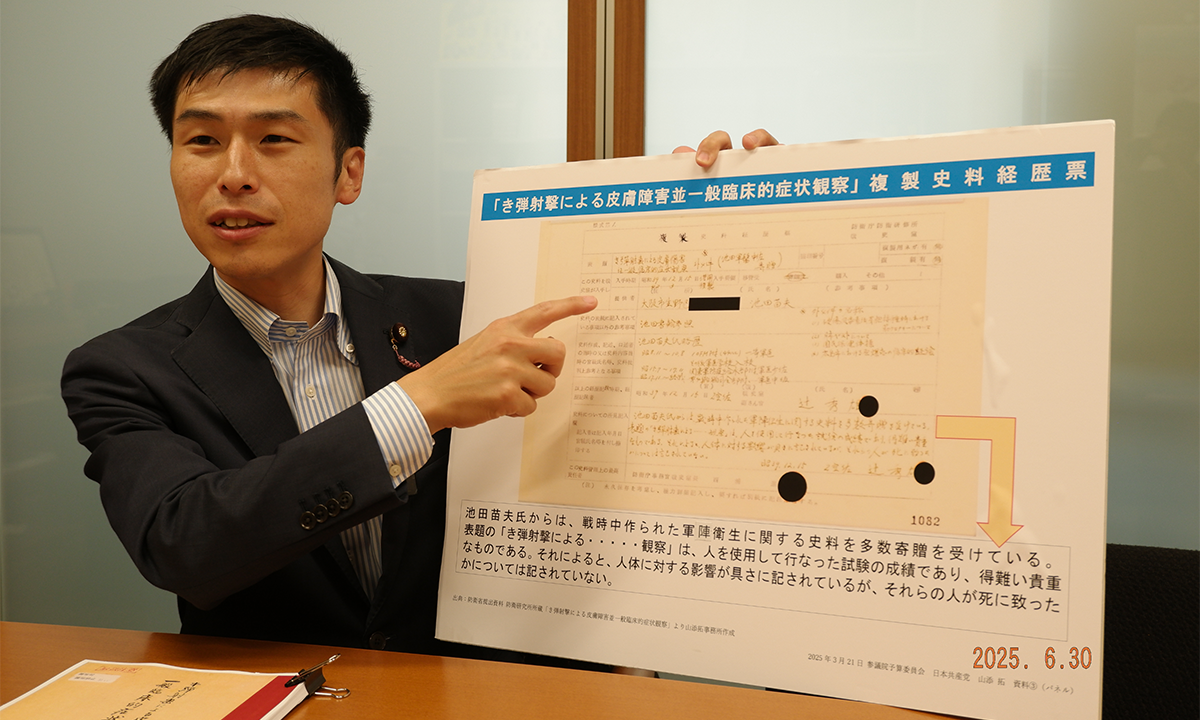

On August 14, the 13th International Memorial Day for "Comfort Women," the book about the complete history of the Japanese "comfort women" system, co-authored by members of the Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women," was released. The publication of this book represents the passing on of a responsibility, chinanews.com reported.

Meanwhile, the struggle for justice continues. At this point, the Global Times spoke with young activists across Asia dedicated to helping survivors defend their rights, spread historical truth, and demand a formal apology and compensation from the Japanese government, ensuring the "comfort women" system is remembered accurately and publicly.

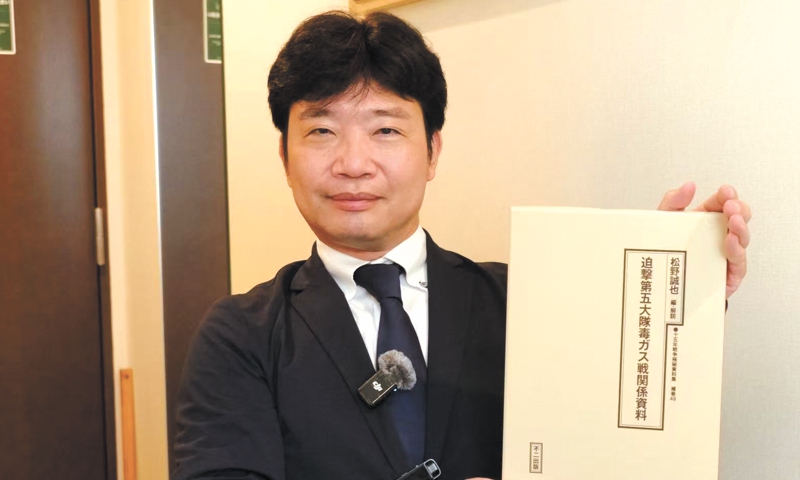

Li Qingling, a researcher at the Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women" at Shanghai Normal University, delivers a speech at a young scholars' symposium in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province on August 9, 2024. Photo: Courtesy of Li Qingling

Unable to look away

"My teacher once said, 'once you know their experiences, you can't just turn away.' I feel the same," Li told the Global Times.

During her master's studies at Shanghai Normal University, Li accompanied her advisor researching the Japanese "comfort women" system, conducting oral history fieldwork with victims based on historical materials. Deeply moved by the survivors' stories, she decided to dedicate herself to this research.

Since 2017, Li and other Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women" team members have interviewed more than a dozen survivors.

In early 2017, she visited 95-year-old survivor Mao Yinmei in Xiaogan, Central China's Hubei Province, whose health situation was declining.

Born in 1922 on the Korean Peninsula, Mao was deceived and taken to China in early 1945, imprisoned in a comfort station in Wuhan, Hubei, and subjected to continuous sexual violence by Japanese soldiers. The brutal abuse resulted in her infertility; she later married and adopted a daughter. Mao lived in China for over 70 years, loved and respected by her family and neighbors.

When Li visited, Mao's health had somewhat improved, and her spirits lifted, but she passed away shortly thereafter.

Another survivor, known as "Xiaorui" (a pseudonym), left a deep impression on Li.

Born in 1930 in Huarong county, Central China's Hunan Province, Xiaorui was kidnapped by the Japanese Imperial Army in 1943 and held with other girls at a local Japanese military stronghold, where they were abused like slaves, including sexually. She kept this secret for over 70 years.

In May 2021, supported and accompanied by her daughter-in-law, Xiaorui recounted her experiences to the research team.

Li recalled that when they finished the interview, Xiaorui became very emotional, repeatedly saying in the Hunan dialect, "There is justice! There is justice!" before covering her face and crying. This scene stayed with Li.

Xiaorui passed away on May 7, 2025 at the age of 96. Following her death, only seven registered survivors of the Japanese military "comfort women" system remain on Chinese mainland, according to Xinhua.

The report said that Xiaorui later lived a peaceful life but regretted never receiving an apology or compensation from Japan.

These experiences have made Li aware of the urgency. "A key prerequisite for a Japanese government apology is admitting the aggression, but that seems to be very difficult. Still, I want to keep working on this."

A wider stage

According to Li, there are a group of Chinese scholars who have long been devoted to this field. At the Shanghai Normal University, Su Zhiliang and Chen Lifei established the Research Center for Chinese "Comfort Women" and led studies that helped install a "comfort women" system victims' statue on campus.

Internationally, Japanese researcher Ishida Yoneko's works systematically documented the sexual violence crimes committed by the Japanese military in North China. Song Yeon-ok, a Korean scholar in Japan, studied the Korean women victim group, Li introduced.

Standing on these foundations, and mindful that Japanese society lacks the voices of Chinese scholars speaking for Chinese victims, Li pursued her PhD at Osaka University in Japan to conduct deeper research to amplify those voices.

Li said that in studying this issue, perspective is as important as the core problem. "Different scholars hold differing, even opposing views, but such clashes help clarify unclear historical facts. Research from various countries helps provide a fuller understanding."

Besides research, Li actively participates in social movements in Japan, organizing and joining public events.

One such effort is Kibotane ("seeds of hope"), a fund for young people to engage in social activities in Japan that aims to raise awareness about the "comfort women" system issue. Many young Japanese people, it says, want to learn but lack historical education or good ways to obtain information. By studying and discussing the issue, they aim to "remember and pass it on" rather than "end it," states the Kibotane official website.

"These study groups mainly involve listening to testimonies from victims from different countries. As someone from the perpetrator country, it is necessary to grasp the essence of aggression by understanding these testimonies. Though each session is heavy, it's the only way to reach the truth. Everyone has a unique feeling from these unfiltered texts," Li said.

"As I studied the issue more deeply, I realized that the 2015 Japan-South Korea comfort women agreement ignored survivors' wishes and excluded those living outside South Korea," Kondo Rintaro, a Kibotane committee member and lecturer at Ryukoku University, told the Global Times.

Still, challenges abound.

"In Japan, while it's possible to access Japanese-language materials and publish articles, this isn't a 'popular' topic," Li said. "It's almost impossible to get scholarships or funding for this research at present."

Social pressure is another hurdle. "Right-wing forces within the Japanese government sometimes collude with right-wing scholars, using their academic status to push government-backed narratives disguised as independent scholarship and spreading them so widely that these views permeate the country," she noted.

Li said that they can also disrupt academic freedom and public gatherings. At one rally she attended, extremists threatened violence; in milder cases, they used loudspeakers to drown out events or blocked participants from attending sometimes.

"The Japanese government has long concealed historical facts," Kondo said.

But Li remains undeterred. "No matter how facts are denied, they cannot be erased. Our goal is to help more people learn the truth."

A spectator visits the Nanjing Museum of the Site of the Lijixiang Comfort Stations in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province on August 14, 2025. Photo: VCG

Young, determined and rising

Su Zhiliang once told Xinhua that researching the history of "comfort women" is painful, and the psychological toll is immense: There is perhaps no cruelty greater than uncovering one's own national history of sexual violence against its women.

Li admitted to having mixed feelings about public outreach. "On the one hand, I want more people to know it. Without public awareness, there's no collective memory. On the other, I worry survivors' suffering could be exploited or sensationalized."

Still, their work continues, drawing more young people to this responsibility.

In August 2024, Li returned from Japan to Nanjing, East China's Jiangsu Province, to attend a young scholars symposium, with nearly 30 young scholars from over 20 universities at home and abroad.

"The symposium is a platform for academic exchange and heritage. For historical research, young scholars' involvement means passing the torch," she said, hoping more young scholars will join "comfort women" system studies.

In Japan, participants in the social activities she helps organize include researchers, students and regular citizens. "Each event averages about 30 people, limited by Japan's population base, around 80 percent of whom are under age 35."

Yamada Yasufumi, a Kibotane committee member, joined after attending the Kibotane lecture series in 2020.

"The lectures allowed me to understand, in detail, the voices and lives of survivors and the litigation process - things barely conveyed by schools or the media. The 'comfort women' system, as organized military sexual violence by the state, was undoubtedly a war crime and violation of human rights. The Japanese government must acknowledge this truth and take responsibility," Yamada told the Global Times.

"Promoting dialogue between younger generations of perpetrator and victim countries is meaningful. Memory transmission is not mere information sharing but a process of deepening awareness through active practice," Yamada added.

Besides, on the 2024 "comfort women" Memorial Day, many students in Seoul joined the 1661st regular rally organized by South Korea's civic group, urging Japan to apologize to and compensate South Korea to restore survivors' honor, CCTV reported.

Hearts are united, but more connections and struggles are needed. As Ishida Yoneko told Li at a recent event, "The 'war' after World War II has never really ended."

Li lamented that although close ties exist between Japan and South Korea, transnational research-sharing networks involving China and the two countries are nearly stagnant. She works to advance this but acknowledges her limited influence and the many tasks that lie ahead.

Kondo said that young Japanese researchers who are interested in the issue remain woefully few. "But because of growing interest in topics like sex education, some young people are engaging more with veteran activists, reading testimonies, watching survivor videos, and even singing or dancing in the streets to raise awareness. These grassroots efforts are spreading across generations, and I'm continuing to take part while deepening my understanding."

Li said she is now preparing her doctoral dissertation for publication while juggling various activities. "Time is running out. Whatever we can do, big or small, is worth doing," she added.

Race against forgetting