Scientists use AI-guided beams to automate cotton topping

Smart plantation in Xinjiang

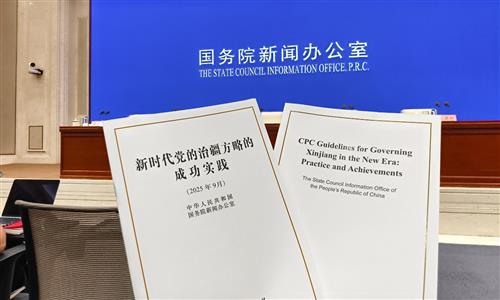

A laser cotton topping robot operates in a test feld in Urumqi, Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Photo: Courtesy of Xinjiang University

In a test field on the campus of Xinjiang University, a white, security machine-like equipment slowly moves along the cotton ridges. From the upper frame, blue laser beams flash intermittently, striking the cotton seedlings below and releasing faint curls of smoke.

This futuristic-looking device — resembling a massive security gate mounted on caterpillar tracks — is the third-generation laser cotton topping robot developed by a team led by Zhou Jianping, principal of the Xinjiang Institute of Engineering and a professor at Xinjiang University. The innovation, Zhou told the Global Times, represents a crucial step toward achieving full-process mechanization, automation and sustainable production in China's cotton-growing sector.

Topping, or the removal of the cotton plant's growth tip, is a vital step in cultivation. Cotton plants tend to grow indefinitely both vertically and horizontally under favorable conditions, prolonging the growth period and reducing yield. Therefore, farmers pinch off the top buds to suppress apical dominance and encourage bountiful boll formation.

Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, which produces over 90 percent of China's cotton, already boasts one of the world's most mechanized cotton production, with machines performing nearly every step — from seeding to harvesting. Yet one barrier has long remained: the automation of cotton topping.

Cotton topping has always been the toughest part in realizing full-process mechanization, Zhou said, adding that "It's the last hard bone to crack."

Traditionally, topping required intense manual labor or chemical inhibitors sprayed by drones — methods that are either laborious, inefficient or environmentally harmful. "Manual topping is physically demanding and slow, while chemical topping risks polluting the soil and water," Zhou explained. "That's why our team seeks for a clean, efficient and intelligent alternative."

Smart cotton topping

In the laboratory of Xinjiang University's School of Mechanical Engineering, Global Times reporters observed the laser cotton topping robot in action. The team demonstrated how the device uses AI-based image recognition to identify each cotton bud with over 99-percent accuracy. High-energy lasers then precisely remove the growth tip without touching the plant, leaving the surrounding tissues undamaged.

For Zhou, the project carries a personal resonance. "I was born and raised in Xinjiang," he said. "When I was a child, I often worked alongside my mother in the cotton fields — hoeing weeds, topping plants, irrigating and harvesting — all by hand," he recalled. "At that time, as a kid, it didn't feel hard for me, but looking back, it was tough for the farmers. Mechanization is what truly liberates them from heavy labor."

"Today, with the help of technology, many farmers can manage their fields without even leaving their homes," Zhou added. "That's what progress should mean."

For decades, cotton farmers around the world have relied on chemical growth inhibitors, first sprayed by manpower and recently by machines and drones, to achieve topping. As this technology has been widely applied in Xinjiang, Zhou's team is worried about its ecological impact. "Xinjiang's natural environment is relatively fragile," said Peng Xuan, a doctoral student in Zhou's team. "Chemical residues can remain in the soil or seep into the water, affecting future crops and damaging the local ecosystem. In contrast, laser topping produces no pollution and helps protect Xinjiang's environment."

Toward global application

In the university's test fields, the laser robot moves autonomously along the ridges, scanning and identifying each plant with high accuracy. Once all six laser modules are installed and fully calibrated, the robot is expected to perform topping work 10 times faster than a human. It can also operate both during the day and at night, unaffected by light conditions.

Since its inception in 2023, the machine has gone through three generations of iteration. The latest version has achieved over 98.9 percent accuracy in identifying cotton buds, a seedling injury rate below 3 percent, and a qualified topping rate exceeding 82 percent.

"We are the first research group to design, build and conduct field experiments for a laser-based cotton topping system," Peng said. "Over the past two years, we've been refining the technology continuously so that it can fill the last missing link in Xinjiang's journey toward 100-percent mechanized cotton cultivation."

The potential global implications are vast. Traditional mechanical topping requires direct contact with the plant, often causing damage to non-target tissues. Chemical topping risks soil degradation and groundwater pollution. Laser topping, however, is a non-contact, precision method that can work seamlessly under varying environmental conditions while being clean and sustainable.

According to data from China's National Bureau of Statistics, Xinjiang's total cotton output reached 5.69 million tons in 2024, with a planting area of approximately 36.72 million mu (2.45 million hectares). The region's share of national cotton production rose to 92.2 percent, a historical record. Meanwhile, the comprehensive mechanization rate of cotton cultivation, planting and harvesting has exceeded 97 percent, and the machine-picking rate has surpassed 90 percent.

The emergence of this laser topping robot could push these figures even higher while transforming cotton cultivation methods worldwide.

Standing beside the sleek, white machine, Zhou pointed out that "The cotton fields of Xinjiang are not only a symbol of China's agricultural modernization but also a testing ground for the technologies that will define the future of sustainable farming."