China postpones Shenzhou-20 return mission; expert explains dangers and sources of tiny space debris

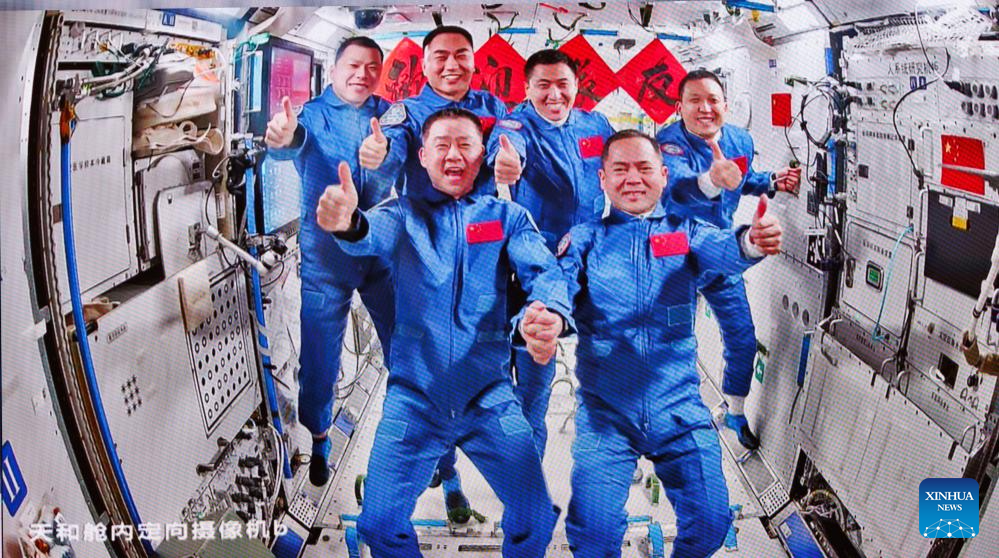

This image captured at Beijing Aerospace Control Center on Nov. 1, 2025 shows a group picture of the crew of Shenzhou-20 and Shenzhou-21 spaceships. The three astronauts aboard China's Shenzhou-21 spaceship have entered the country's space station and met with another astronaut trio early Saturday morning, starting a new round of in-orbit crew handover. The Shenzhou-20 crew opened the hatch at 4:58 a.m. (Beijing Time) and greeted the new arrivals, according to the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA). The six crew members then took group pictures for the seventh space get-together in China's aerospace history. They will live and work together for about five days to complete planned tasks and handover work, the CMSA said. (Xinhua/Jin Liwang)

The return of China's Shenzhou-20 crewed spacecraft, originally scheduled for Wednesday, has been postponed due to a suspected impact from tiny space debris, the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) announced. A Chinese expert explained to the Global Times the potential dangers, main sources, and countermeasures related to such debris.

The impact analysis and risk assessment are under way, and the decision to delay the return aims to ensure the astronauts' safety and mission success, CMSA said.

Pang Zhihao, a senior space expert, told the Global Times on Wednesday that discarded spacecraft and related components are the main and most direct sources of space debris, accounting for more than 40 percent. These include decommissioned satellites, rocket remnants and fragments from disintegrated spacecraft.

He added that another major source is operational waste generated during space missions - objects intentionally or unintentionally discarded in orbit. Though small in size, these fragments are vast in number. They include functional discardables such as bolts released during satellite separation, rocket fairings, or tools dropped by astronauts, as well as micro-particles from peeling surface coatings, tiny solar panel fragments, and engine combustion residue.

Pang noted that collisions and explosions between spacecraft have become a crucial factor behind the increase in orbital debris. Historical incidents of satellite-to-debris or satellite-to-satellite collisions have triggered chain reactions, with each impact generating new fragments that can strike other spacecraft - creating a "debris avalanche" that exponentially increases orbital density.

"Don't underestimate the power of space debris," Pang warned. Even fragments smaller than one centimeter can cause catastrophic damage due to their immense kinetic energy at speeds of seven to 10 kilometers per second. Millimeter-sized debris can scratch spacecraft windows and solar panels, reducing light transmission or power generation efficiency, while centimeter-sized fragments can puncture fuel tanks or pipelines, causing leaks or explosions.

Even if not fully penetrated, the resulting shock waves can disable delicate onboard instruments, disrupting navigation and communication systems, Pang said.

When the density of debris in low Earth orbit reaches a critical level, one collision can trigger a chain of impacts - a "domino effect" - forming a "debris cloud" that could severely hinder future human access to space or satellite operations, Pang cautioned.

According to Pang, two primary techniques are used to monitor and predict debris impacts, including optical observation, which captures sunlight reflected by debris and is suitable for high-orbit detection, and radar monitoring, which sends and receives electromagnetic signals to track debris position and speed with all-weather capability. Advanced systems can detect debris as small as a few millimeters and provide centimeter-level precision.

Emerging technologies such as lidar, adaptive optics, and multi-sensor fusion are improving accuracy and resilience under complex conditions, Pang noted.

Lidar technology can provide high temporal resolution and update debris positions in real time, while adaptive optics help overcome atmospheric interference, improving detection performance at night or under complex weather conditions.

Multi-sensor fusion technology integrates data from radar, optical, and lidar systems to create a complementary monitoring network. By using data fusion algorithms, it overcomes the limitations of individual sensors, enhances debris identification and tracking accuracy, and supports 3D spatial reconstruction, generating real-time debris distribution maps for intuitive collision risk assessment.

Collision probability analysis combines orbital error models with alert zone determinations to set reasonable probability thresholds, reducing false alarms and improving spacecraft avoidance efficiency, said the expert.

As for mitigation, Pang said spacecraft mainly relies on active orbit adjustments for large debris and passive shielding for smaller particles. Researchers are also developing debris removal methods such as laser ablation, space nets, robotic arms, ion beam deflection and electromagnetic capture.