IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Dangerous ideological poison: How Japanese right-wing groups indoctrinate elementary school students with militarism

The Japanese Ministry of Defense (MOD) is facing pushback from educators' groups as it recently distributed a children's version of the Japan Defense White Paper to elementary schools nationwide. Teachers and staff criticized the booklet for containing militaristic overtones, arguing that it essentially serves as a recruitment advertisement for the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) and infringes on children's rights. The Japanese Communist Party and several democratic groups have demanded that the MOD and local governments withdraw the booklet.

Right-wing forces in Japan have been quietly trying to introduce militaristic ideology into primary and secondary schools in recent years in order to pave the way for policies aimed at strengthening and expanding the military. Such actions violate the spirit of Japan's postwar pacifist constitution; distort young people's understanding of history and war; undermine trust between Japan and neighboring countries; and pose a threat to regional peace and stability.

6,100 booklets to 2,400 schools

In response to the distribution of the children's version of the defense white paper, the All Japan Teachers and Staff Union (Zenkyo) and other educators' groups directly petitioned officials from Japan's MOD and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology on December 1. They criticized the booklet, arguing that it may violate the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Convention was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989 and formally ratified by Japan in 1994. Article 38 of the Convention explicitly requires state parties to refrain from recruiting children under the age of 15 into their armed forces.

The distribution of a children's version of the defense white paper is one of the main methods used by right-wing forces in Japan in recent years to influence teenagers with militaristic ideology. The Japanese government first released the Defense White Paper in 1970 and has published it annually since 1976. Since 2021, the Japanese MOD has compiled a children's version of the report each year. Initially, it was only released online, but the 2024 edition was the first to be distributed to elementary schools. As of now, approximately 6,100 copies have been distributed to 2,400 schools that agreed to receive them, including schools in Nagasaki, Fukushima, Aomori, and other regions.

The Global Times found an online version of the booklet on the website of the Japanese MOD. Most of the kanji characters in it are accompanied by furigana (phonetic readings), and the text is supplemented with pictures and cartoons. Each chapter includes a Q&A section. In the guise of a children's book, the booklet presents complex security issues through a one-sided logic of threats from neighboring countries, the necessity to expand military forces, and indoctrinates minors with an image of the JSDF as a career choice, laying the groundwork for recruitment.

The booklet contains four parts. The first section, "why the Self-Defense Forces are necessary," repeatedly emphasizes that deterrence is crucial for preventing war. The second section, "what's happening around Japan," points to China, North Korea, and Russia as the sources of so-called military threats, drawing the narrow conclusion that the region where Japan is located is not safe. Regarding US military presence in Japan and the Japan-US military alliance, it only highlights how it provides security to regional countries, completely avoiding the fact that the presence of foreign troops could exacerbate tensions. The third section, "what Japan should do," attempts to rationalize Japan's growing military budget, claiming that so-called counterattack capabilities are key to enhancing defense strength. The white paper uses numerous illustrations and photos to package weaponry, war costs, and combat strategies as so-called interesting and easy-to-understand information, essentially selling the idea of a strengthened military and expanded weaponry to the youth. The fourth section introduces the disaster relief functions of the JSDF.

The 2025 version of Japan's Defense White Paper is already available online and reportedly includes more content than before explaining the various roles within the JSDF and the process from application to enlistment.

Along with the booklet, a survey was also distributed, which includes a question on how the White Paper is being utilized during integrated learning time. This clearly indicates the intention for teachers to incorporate the White Paper into classroom teaching hours.

Public attention and opposition

The Japanese government's move to introduce the defense white paper into school campuses has sparked concern and opposition from the country's education sector. "We must stop the one-sided indoctrination of children with the national policy of 'strengthening the military,'" said Nobuko Murata, a central executive committee member of the All Japan Teachers and Staff Union, during a question session with officials from the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, according to the Tokyo Shimbun on December 2.

Many schools have already decided to keep the white paper out of students' reach. According to Shimbun Akahata, a news website of the Japanese Communist Party, Nagasaki city has explicitly instructed schools not to place the booklet where students can access it; after all the teachers at an elementary school in Fukushima Prefecture read through the booklet, they unanimously agreed that the problems are severe. A teacher in his sixties commented: "I felt uncomfortable with the content of militaristic education, and I should convey various ideas to children and let them think independently."

According to TBS News Dig in July 2025, Keiko Nakamura, associate professor at the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition at Nagasaki University, said the white paper explains Japan's security solely from the perspective of strengthening military power to achieve deterrence.

In reality, Japan's foreign policy should encompass multiple dimensions, enhancing diplomatic relations, deepening economic ties, engaging in international cooperation, and promoting arms control and nuclear non-proliferation. Given that elementary school students have not yet developed the capacity for multi-angled or critical thinking, instilling in them a singular "strong military" perspective is extremely dangerous and may lead them to a simplistic understanding that Japan's security can only be protected by military force, Nakamura said.

Akira Tomizuka, executive director of the Nagasaki peace committee, said that deterrence means using force to compel the other side to yield, and this runs counter to the values of equality and mutual respect taught in schools, reported Shimbun Akahata.

According to the Tokyo Shimbun, Kokoro Fukumoto, a member of the central standing committee of the New Japan Women's Association, said that if children from the countries named in the white paper are bullied or discriminated against, who will take responsibility?

Distributing the children's version of the defense white paper is, in fact, only one tactic used by Japan's right-wing forces to inject militarism into youth education. Professor Lian Degui, director of the Center for Japanese Studies at the Shanghai International Studies University, told the Global Times that militarism remains a highly sensitive topic in postwar Japan and is rarely discussed openly by the media or in official discourse. However, the developments within Japan's right-wing circles are cause for concern. For example, some principals with right-leaning views reportedly use wartime militarist teaching materials in their classes.

According to the Tokyo Shimbun in May 2024, an after-school center near an elementary school in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, held an event called the "JSDF Experience." Under the guidance of Self-Defense Force personnel, children practiced JSDF-style formations, roll calls, and salutes, watched promotional videos, and received pamphlets introducing the performance of JSDF fighter jets and destroyers, along with notebooks printed with QR codes linking to JSDF recruitment videos.

The report noted that some children were pulled into the event by staff on site, and many participated without their parents' consent. The father of a lower-grade student expressed concern: "I never applied for this. I was shocked to find out my child was going through military-style training. The JSDF is an organization that uses weapons in combat when necessary. Are such activities for students really appropriate?"

Tetsuhiko Nakajima, professor emeritus at Nagoya University, commented that they need a clear explanation of why children are being encouraged to experience the JSDF now, reported the Tokyo Shimbun.

In fiscal year 2023, the number of school activities organized by the regional cooperation offices responsible for JSDF recruitment - including "base and camp tours," "on-site experiential programs," and "JSDF personnel lectures" - reached its highest level in nearly five years. A total of 2,626 such activities were conducted nationwide, marking a 1.6-fold increase compared with fiscal year 2019, reported the Shimbun Akahata on August 2024.

Entrenching negative legacy of wrong path

In recent years, the Japanese government has reintroduced military training items from its militarist period. According to Xinhua News Agency, in March 2017, under the administration of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology released new curriculum guidelines for elementary and junior high schools, adding jukendo, or "way of the bayonet" in the physical education curriculum. This training was a key combat skill for the Imperial Japanese Army during the militarist era.

Japanese military journalist and former Self-Defense Force member Makoto Konishi criticized the move, stating that bayonet fencing should not be included in the national curriculum. It is essentially close-combat training for the Self-Defense Forces. Introducing such combat skills into school education is a revival of wartime military drills.

The Ryukyu Shimpo published an editorial stating that the Rescript was inseparable from militarist education during the Showa era, calling it a negative legacy from a period of the wrong path that fundamentally conflicted with the principles of Japan's current constitution. Notably, in September 2012, Sanae Takaichi, then a Liberal Democratic Party member of the House of Representatives, wrote on her personal website about national education, recalling that her parents had repeatedly taught her the Imperial Rescript on Education in her childhood. She claimed its content reflects correct values that should still be respected today.

"Right-wing politicians constantly find excuses to reintroduce the Rescript into schools," said Meiji University associate professor Asao Naito in a social media post in late November. Critics argue that its content could lead to militarist viewpoints.

Over two decades ago, an elderly Japanese woman sincerely apologized to a Global Times correspondent in Japan for the suffering inflicted on the Chinese people during WWII. As someone who experienced the war firsthand, her memories were not abstract "security concepts" but concrete fears, hunger, and loss. Her reflection on history stemmed from personal experience, not political propaganda.

As war survivors gradually grow old or pass away, education on war history becomes increasingly important. However, Japanese right-wing forces narrowly define war as "deterrence" and describe arms expansion as a "necessary preparation," promoting the assertion that "more weapons are needed" without guiding the younger generation to truly understand war history. This educational method that severs historical truth has undoubtedly exacerbated the collective memory gap in Japanese society.

Relevant experts believe that if Japan's younger generation lacks historical knowledge and accepts the "enemy narrative" and arguments justifying arms expansion, the direction of Japanese society may go off the rails again.

Right-wing forces in Japan have been quietly trying to introduce militaristic ideology into primary and secondary schools in recent years in order to pave the way for policies aimed at strengthening and expanding the military. Such actions violate the spirit of Japan's postwar pacifist constitution; distort young people's understanding of history and war; undermine trust between Japan and neighboring countries; and pose a threat to regional peace and stability.

6,100 booklets to 2,400 schools

In response to the distribution of the children's version of the defense white paper, the All Japan Teachers and Staff Union (Zenkyo) and other educators' groups directly petitioned officials from Japan's MOD and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology on December 1. They criticized the booklet, arguing that it may violate the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Convention was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989 and formally ratified by Japan in 1994. Article 38 of the Convention explicitly requires state parties to refrain from recruiting children under the age of 15 into their armed forces.

The distribution of a children's version of the defense white paper is one of the main methods used by right-wing forces in Japan in recent years to influence teenagers with militaristic ideology. The Japanese government first released the Defense White Paper in 1970 and has published it annually since 1976. Since 2021, the Japanese MOD has compiled a children's version of the report each year. Initially, it was only released online, but the 2024 edition was the first to be distributed to elementary schools. As of now, approximately 6,100 copies have been distributed to 2,400 schools that agreed to receive them, including schools in Nagasaki, Fukushima, Aomori, and other regions.

The children's version of the 2024 Defense White Paper of Japan Photo: website of All Japan Teachers and Staff Union

The Global Times found an online version of the booklet on the website of the Japanese MOD. Most of the kanji characters in it are accompanied by furigana (phonetic readings), and the text is supplemented with pictures and cartoons. Each chapter includes a Q&A section. In the guise of a children's book, the booklet presents complex security issues through a one-sided logic of threats from neighboring countries, the necessity to expand military forces, and indoctrinates minors with an image of the JSDF as a career choice, laying the groundwork for recruitment.

The booklet contains four parts. The first section, "why the Self-Defense Forces are necessary," repeatedly emphasizes that deterrence is crucial for preventing war. The second section, "what's happening around Japan," points to China, North Korea, and Russia as the sources of so-called military threats, drawing the narrow conclusion that the region where Japan is located is not safe. Regarding US military presence in Japan and the Japan-US military alliance, it only highlights how it provides security to regional countries, completely avoiding the fact that the presence of foreign troops could exacerbate tensions. The third section, "what Japan should do," attempts to rationalize Japan's growing military budget, claiming that so-called counterattack capabilities are key to enhancing defense strength. The white paper uses numerous illustrations and photos to package weaponry, war costs, and combat strategies as so-called interesting and easy-to-understand information, essentially selling the idea of a strengthened military and expanded weaponry to the youth. The fourth section introduces the disaster relief functions of the JSDF.

The 2025 version of Japan's Defense White Paper is already available online and reportedly includes more content than before explaining the various roles within the JSDF and the process from application to enlistment.

Along with the booklet, a survey was also distributed, which includes a question on how the White Paper is being utilized during integrated learning time. This clearly indicates the intention for teachers to incorporate the White Paper into classroom teaching hours.

Public attention and opposition

The Japanese government's move to introduce the defense white paper into school campuses has sparked concern and opposition from the country's education sector. "We must stop the one-sided indoctrination of children with the national policy of 'strengthening the military,'" said Nobuko Murata, a central executive committee member of the All Japan Teachers and Staff Union, during a question session with officials from the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, according to the Tokyo Shimbun on December 2.

Many schools have already decided to keep the white paper out of students' reach. According to Shimbun Akahata, a news website of the Japanese Communist Party, Nagasaki city has explicitly instructed schools not to place the booklet where students can access it; after all the teachers at an elementary school in Fukushima Prefecture read through the booklet, they unanimously agreed that the problems are severe. A teacher in his sixties commented: "I felt uncomfortable with the content of militaristic education, and I should convey various ideas to children and let them think independently."

Murata Nobuko (right), a central executive committee member of the All Japan Teachers and Staff Union, explains issues concerning the Japanese Defense Ministry's distribution of a children's version of the 2024 Defense White Paper to elementary schools during an inquiry in Japan on December 1, 2025. Photo: website of Tokyo Shimbun

According to TBS News Dig in July 2025, Keiko Nakamura, associate professor at the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition at Nagasaki University, said the white paper explains Japan's security solely from the perspective of strengthening military power to achieve deterrence.

In reality, Japan's foreign policy should encompass multiple dimensions, enhancing diplomatic relations, deepening economic ties, engaging in international cooperation, and promoting arms control and nuclear non-proliferation. Given that elementary school students have not yet developed the capacity for multi-angled or critical thinking, instilling in them a singular "strong military" perspective is extremely dangerous and may lead them to a simplistic understanding that Japan's security can only be protected by military force, Nakamura said.

Akira Tomizuka, executive director of the Nagasaki peace committee, said that deterrence means using force to compel the other side to yield, and this runs counter to the values of equality and mutual respect taught in schools, reported Shimbun Akahata.

According to the Tokyo Shimbun, Kokoro Fukumoto, a member of the central standing committee of the New Japan Women's Association, said that if children from the countries named in the white paper are bullied or discriminated against, who will take responsibility?

Distributing the children's version of the defense white paper is, in fact, only one tactic used by Japan's right-wing forces to inject militarism into youth education. Professor Lian Degui, director of the Center for Japanese Studies at the Shanghai International Studies University, told the Global Times that militarism remains a highly sensitive topic in postwar Japan and is rarely discussed openly by the media or in official discourse. However, the developments within Japan's right-wing circles are cause for concern. For example, some principals with right-leaning views reportedly use wartime militarist teaching materials in their classes.

According to the Tokyo Shimbun in May 2024, an after-school center near an elementary school in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, held an event called the "JSDF Experience." Under the guidance of Self-Defense Force personnel, children practiced JSDF-style formations, roll calls, and salutes, watched promotional videos, and received pamphlets introducing the performance of JSDF fighter jets and destroyers, along with notebooks printed with QR codes linking to JSDF recruitment videos.

The report noted that some children were pulled into the event by staff on site, and many participated without their parents' consent. The father of a lower-grade student expressed concern: "I never applied for this. I was shocked to find out my child was going through military-style training. The JSDF is an organization that uses weapons in combat when necessary. Are such activities for students really appropriate?"

Tetsuhiko Nakajima, professor emeritus at Nagoya University, commented that they need a clear explanation of why children are being encouraged to experience the JSDF now, reported the Tokyo Shimbun.

In fiscal year 2023, the number of school activities organized by the regional cooperation offices responsible for JSDF recruitment - including "base and camp tours," "on-site experiential programs," and "JSDF personnel lectures" - reached its highest level in nearly five years. A total of 2,626 such activities were conducted nationwide, marking a 1.6-fold increase compared with fiscal year 2019, reported the Shimbun Akahata on August 2024.

Entrenching negative legacy of wrong path

In recent years, the Japanese government has reintroduced military training items from its militarist period. According to Xinhua News Agency, in March 2017, under the administration of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology released new curriculum guidelines for elementary and junior high schools, adding jukendo, or "way of the bayonet" in the physical education curriculum. This training was a key combat skill for the Imperial Japanese Army during the militarist era.

Japanese military journalist and former Self-Defense Force member Makoto Konishi criticized the move, stating that bayonet fencing should not be included in the national curriculum. It is essentially close-combat training for the Self-Defense Forces. Introducing such combat skills into school education is a revival of wartime military drills.

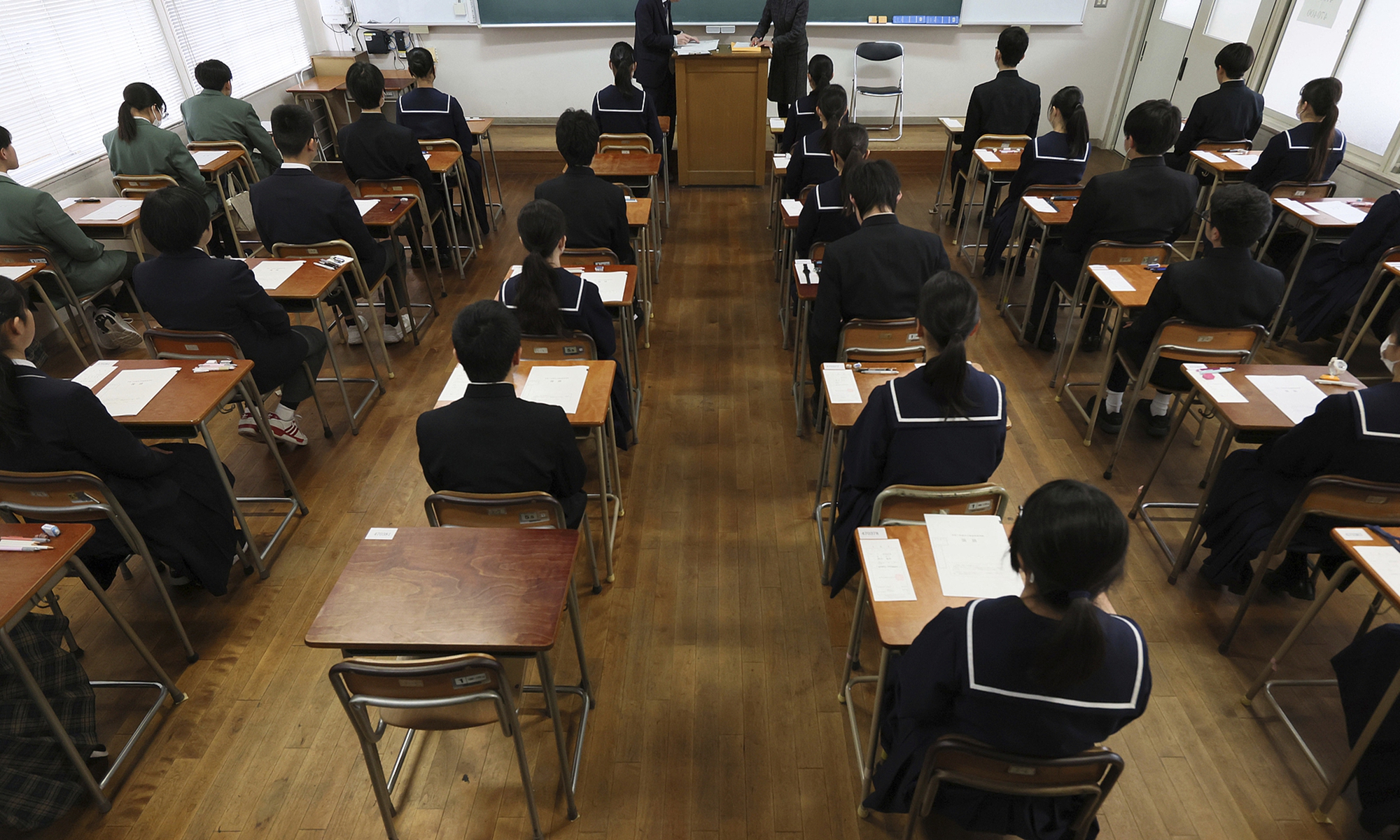

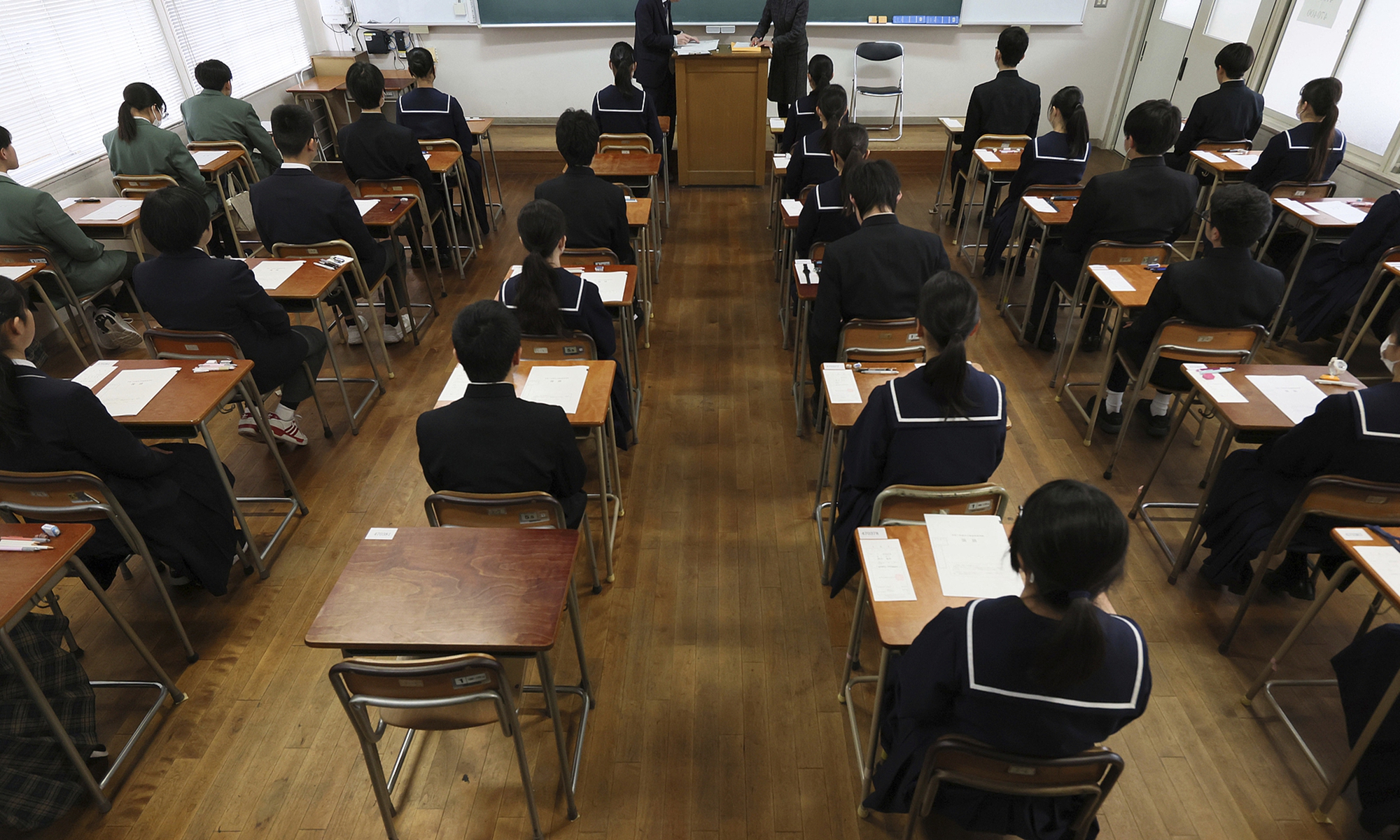

A classroom in Japan Photo: VCG

During Abe's tenure, the Moritomo Gakuen in Osaka received praise from him for its efforts to revive militarist education. In 2017, a video of students at Morimoto Gakuen's Tsukamoto Kindergarten, reciting the Imperial Rescript on Education sparked widespread criticism. The edict issued by Emperor Meiji in 1890 served alongside the Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors as one of the two pillars of prewar militarist education. After World War II, the Japanese Diet abolished it. However, in March 2017, the Abe administration approved a statement declaring that the edict can be used as teaching material in schools, the Japan Times reported.The Ryukyu Shimpo published an editorial stating that the Rescript was inseparable from militarist education during the Showa era, calling it a negative legacy from a period of the wrong path that fundamentally conflicted with the principles of Japan's current constitution. Notably, in September 2012, Sanae Takaichi, then a Liberal Democratic Party member of the House of Representatives, wrote on her personal website about national education, recalling that her parents had repeatedly taught her the Imperial Rescript on Education in her childhood. She claimed its content reflects correct values that should still be respected today.

"Right-wing politicians constantly find excuses to reintroduce the Rescript into schools," said Meiji University associate professor Asao Naito in a social media post in late November. Critics argue that its content could lead to militarist viewpoints.

Over two decades ago, an elderly Japanese woman sincerely apologized to a Global Times correspondent in Japan for the suffering inflicted on the Chinese people during WWII. As someone who experienced the war firsthand, her memories were not abstract "security concepts" but concrete fears, hunger, and loss. Her reflection on history stemmed from personal experience, not political propaganda.

As war survivors gradually grow old or pass away, education on war history becomes increasingly important. However, Japanese right-wing forces narrowly define war as "deterrence" and describe arms expansion as a "necessary preparation," promoting the assertion that "more weapons are needed" without guiding the younger generation to truly understand war history. This educational method that severs historical truth has undoubtedly exacerbated the collective memory gap in Japanese society.

Relevant experts believe that if Japan's younger generation lacks historical knowledge and accepts the "enemy narrative" and arguments justifying arms expansion, the direction of Japanese society may go off the rails again.