Chen Rong, daughter of Chen Deshou tells the story of his father on December 11, 2025. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

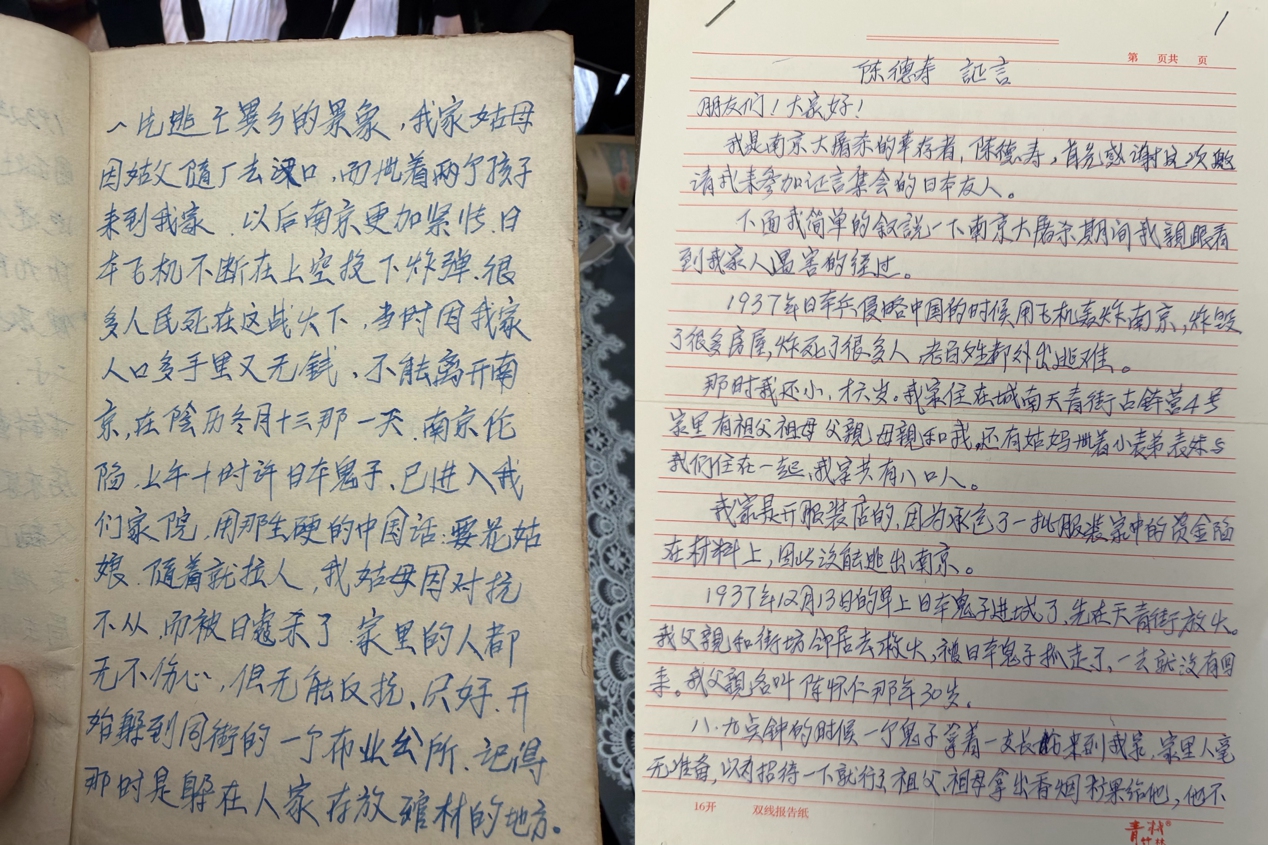

Two days before the 12th National Memorial Day for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre, which fell on Saturday this year, Chen Rong, a resident of Nanjing in East China's Jiangsu Province, came across an old notebook at home while preparing for an interview with the Global Times about her father, Chen Deshou—an eyewitness and survivor of the massacre. Written neatly in blue ink by Chen Deshou, the yellowed pages recorded what happened to their family after Japanese troops captured Nanjing on December 13, 1937.

In December 1937, invading Japanese troops carried out the Nanjing Massacre, killing more than 300,000 Chinese civilians and disarmed soldiers. Members of Chen Deshou's family were among the victims. He is now one of the 24 registered survivors of the massacre still alive.

Chen Deshou, an eyewitness and survivor of the Nanjing Massacre, goes to Kumamoto, Japan in December 2014 to give testimony. Photo: Courtesy of Chen Rong

Chen Deshou's handwritten testimony Photo: Liu Xin/GT

Chen Rong told the Global Times that she can no longer recall exactly when her father first wrote those notes. She does, however, clearly remember another handwritten account on lined paper a testimony Chen Deshou prepared in December 2014, when traveling to Japan to give testimony about the massacre. The document begins simply: "Hello everyone, I am Chen Deshou, a survivor of the Nanjing Massacre."

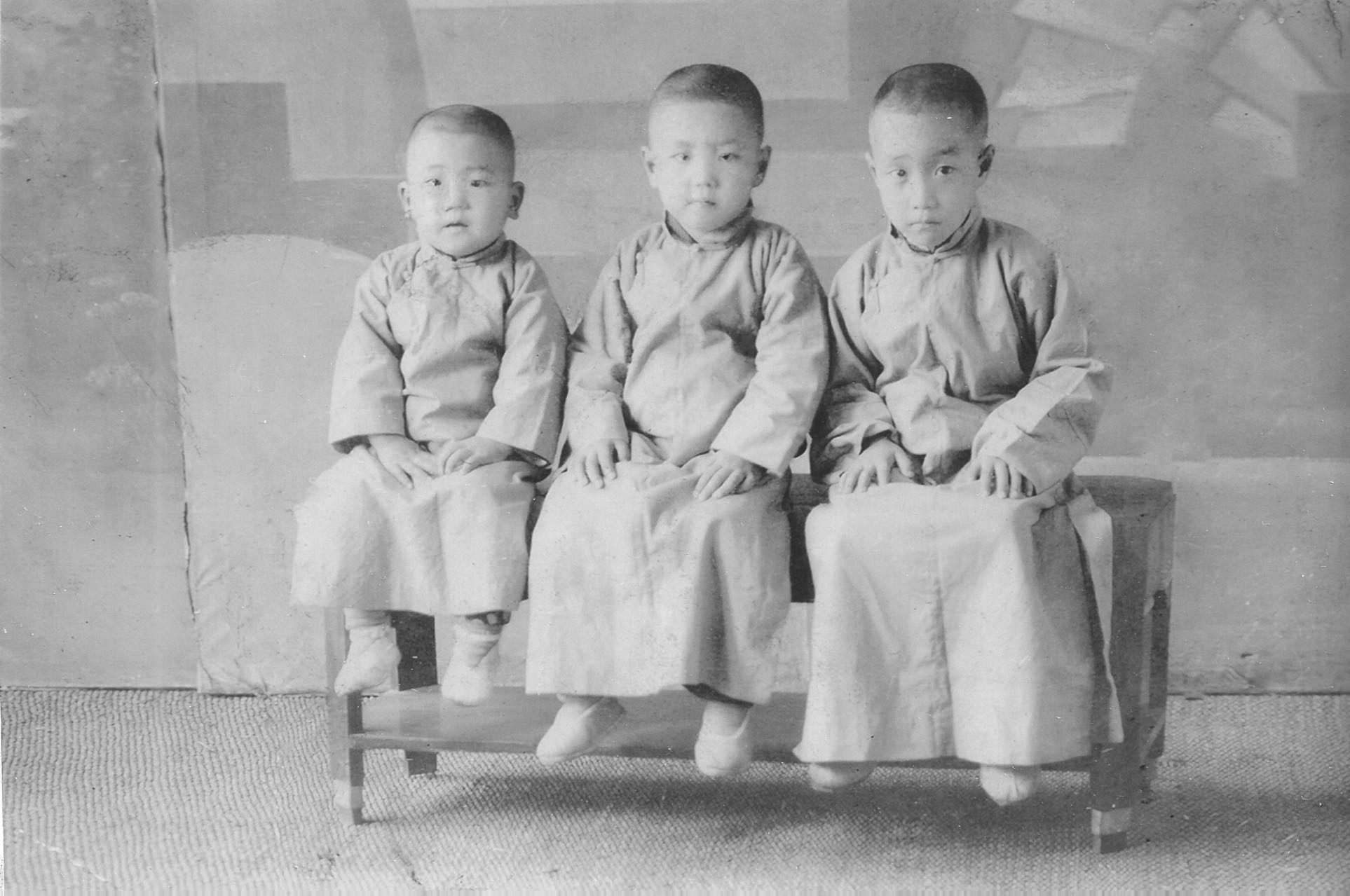

He went on to describe how Japanese forces bombed Nanjing in 1937, destroying homes and killing civilians. At the time, he was just six years old. His family lived on Tianqing Street in the southern part of the city. Eight people shared the household: his grandparents, parents, himself, and his aunt, who lived with them along with her young son and daughter.

Chen Deshou (right) as a child Photo: Courtesy of Chen Rong

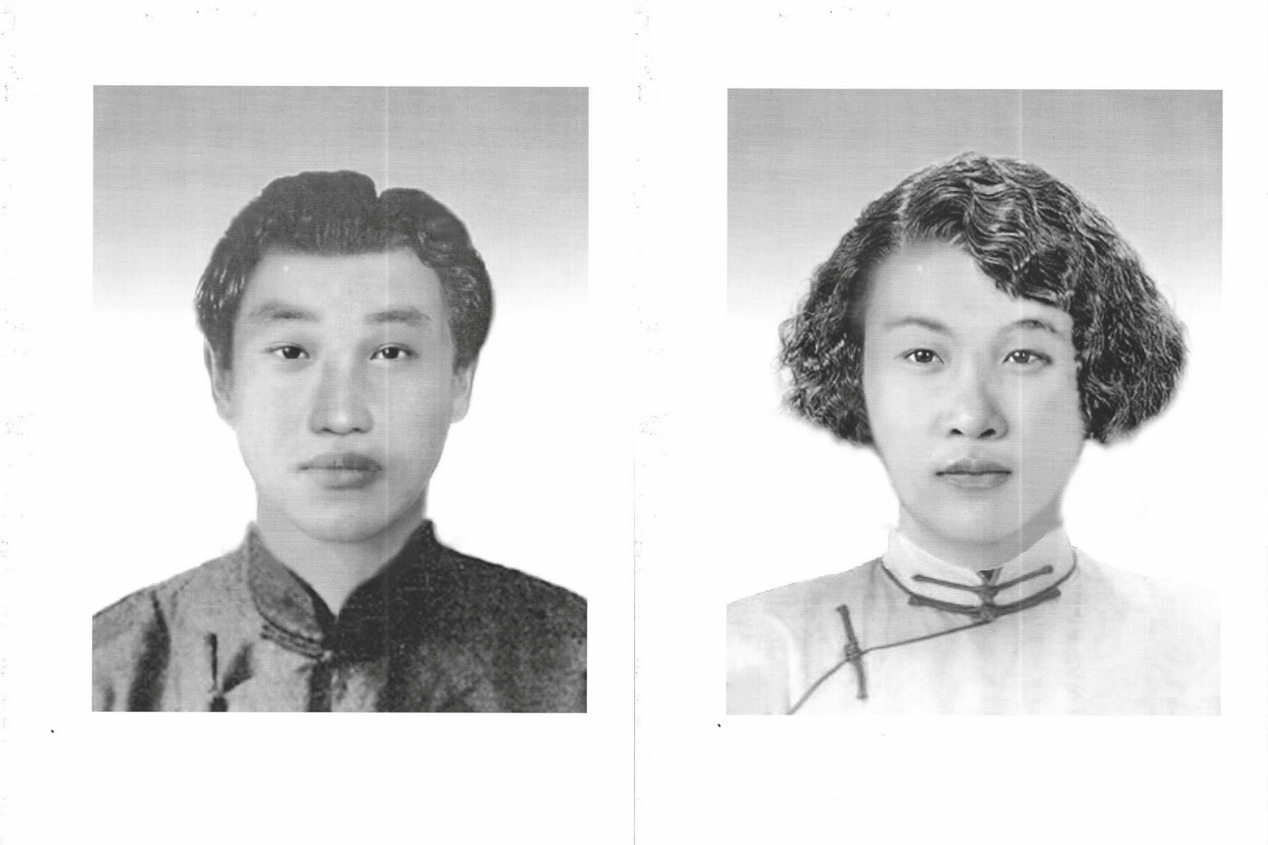

On the morning of December 13, Japanese soldiers entered the city. Killing and arson followed almost immediately. Chen Deshou's father, who was then 30-year-old went to put out the fire with neighbors, had never came back. Around eight or nine o'clock that morning, a Japanese soldier broke into the Chen family home. He demanded a "hua guniang"—a young woman. Chen Deshou's mother was heavily pregnant and confined to bed, and the soldier dragged away his aunt. She resisted. Enraged, the soldier pulled out his bayonet and stabbed her repeatedly—six times in the thigh—before leaving, Chen Deshou wrote on the lined paper.

Photos of Chen Deshou's father Chen Huairen and aunt Chen Baozhu Photos: Courtesy of Chen Rong

"My aunt fell to the ground, bleeding," Chen Deshou wrote. "She said to my grandmother, 'Mom, it hurts so much. Give me some sugar water.'" His grandmother went to prepare it, but when she returned, the aunt had already died. Chen Deshou noted that his aunt's name was Baozhu—meaning "precious"—and that she was 27 years old at the time.

The aunt's body was placed on a makeshift stretcher fashioned from a wooden door and was not buried until six days later.

That same night, Chen Deshou's mother gave birth to a baby girl. In his written account, Chen recalled that Japanese soldiers continued to come to the house in the days that followed. Bloodstained cloths from the childbirth lay beside his mother's bed, and at times the soldiers even lifted the quilt covering her.

The family later learned that Chen Deshou's father—who had gone missing earlier while trying to put out fires—had also been killed by Japanese soldiers, stabbed once in the temple and once in the neck. A neighbor wrapped his body in a quilt and hid it in an air-raid shelter. It was not until 40 days later that Chen Deshou's grandfather and uncle were able to retrieve the body and bury him outside Zhonghuamen, according to one of his handwritten testimonies.

With his father dead, the family lost its main source of income. Life grew increasingly difficult, and they survived by selling off their remaining property. The two children brought by Chen Deshou's aunt were separated—one sent to an orphanage, the other given away as an adopted child. That same year, Chen Deshou's grandmother and infant sister died of disease. To raise money for funerals, his mother was forced to remarry.

From a household of eight, only Chen Deshou and his grandfather remained. A once-complete family was reduced to one old man and one child.

Chen Deshou buried these memories deep within himself. When Chen Rong and her brother were children, they heard only fragments of the story, mentioned casually by their father, without fully understanding what he had endured.

Chen Rong, daughter of Chen Deshou tells the story of his father on December 11, 2025. Photo: Cui Meng/GT

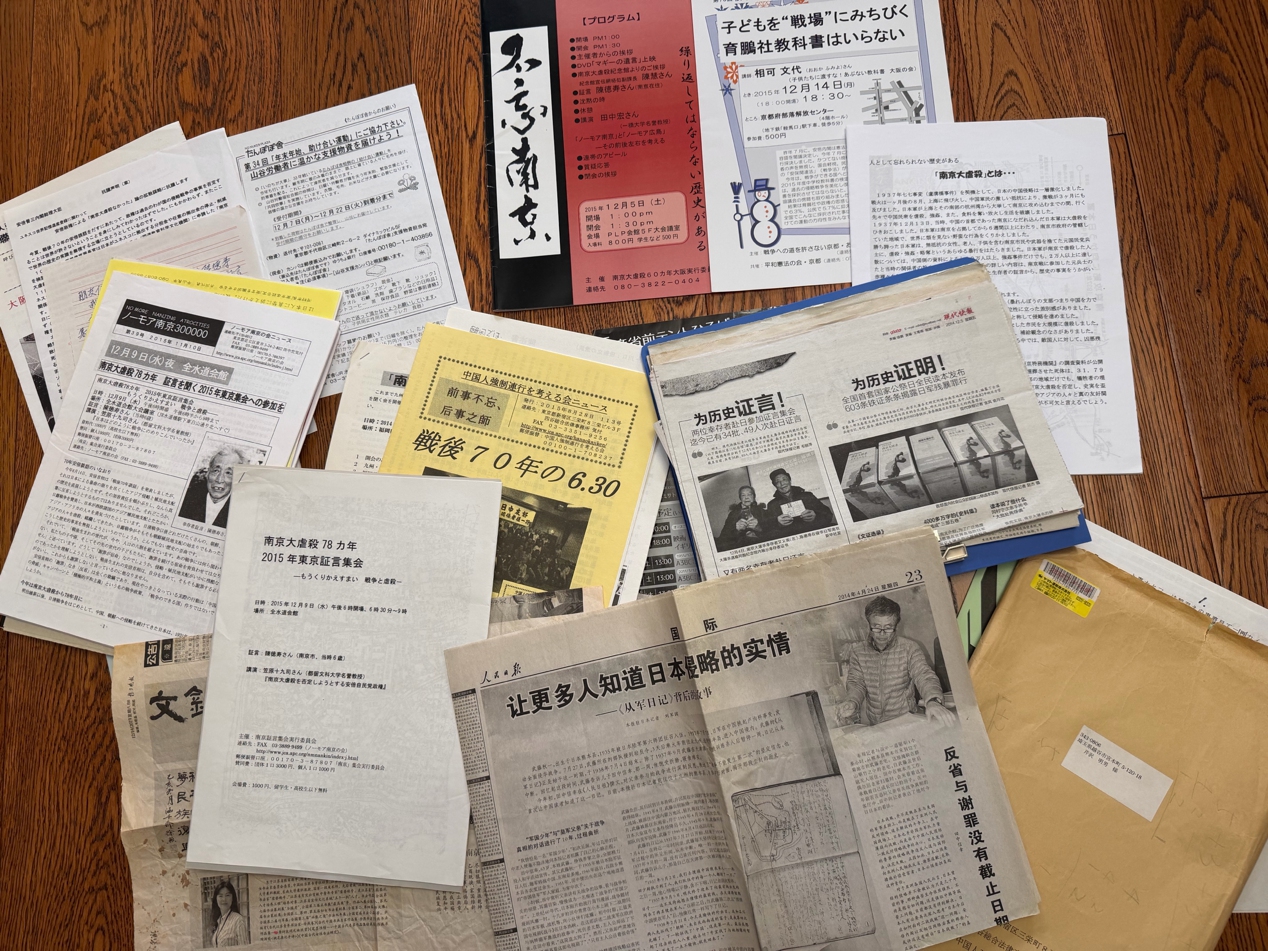

It was not until 2014, when Chen Rong accompanied her father to give testimony about the Nanjing Massacre, that she learned the full extent of his experience—and that each time he recounts what happened, he is unable to sleep for several nights afterward.

"That was the first time I truly learned what he went through during the Nanjing Massacre," Chen Rong told the Global Times through tears, noting that the trauma shaped her father's entire life.

As she grew older, Chen Rong said she began to see her father's experience in a broader light—and came to admire his outlook. "I really respect him," she said. "He didn't just talk about how much suffering he endured personally, even though he suffered enormously. He said war is the real source of suffering."

Documents, brooklets and reports on Nanjing Massacre survivors' testimonies in Japan in 2014 and 2015, collected by Chen Deshou Photo: Liu Xin/GT

Accompanied by other family members, Chen Deshou had traveled to Japan to testify and visited several cities, including Nagasaki. At the atomic bomb memorial there, one photograph struck him deeply: a child carrying a dead sibling on their back, standing by a river, waiting for cremation. "My father said that image moved him profoundly. He realized that the war Japan launched also brought immense suffering to its own people," Chen Rong said.

From then on, Chen Deshou consistently emphasized one message after every public speech. "He always said that war brings pain not only to the country that is invaded, but also to the country that launches the war and It's not short-term suffering—it's pain that lasts for generations," Chen Rong recalled.

Earlier this year, Chen Rong traveled to Japan at her own expense to better understand Japanese society today. She visited Kumamoto, Nagasaki and Fukuoka with her father. She remains closely engaged with issues of historical memory. In September this year, she hosted a group of Japanese visitors who were committed to reflecting on wartime history. But she worries that such voices are becoming fewer.

"The people in Japan who are willing to reflect are getting older," she said. "That group is shrinking, together with the consciousness of Japan is shrinking," Chen Rong told the Global Times.

Her concern, she said, is about the danger of war itself. "I'm not worried that our country can't defend itself," she said. "I'm worried about certain right-wing figures stirring up conflict." War, she said, is inherently cruel. "But if someone keeps provoking you, keeps pushing you toward confrontation, what choice do you have?" she asked.

Chen Rong said that Chinese people seek peace. "We want to live our lives well," she said. "But if you keep bullying and provoking us, we can't just accept it. We have to protect our people and our national interests."

For her, remembering the Nanjing Massacre is not about perpetuating hatred. "It's about making the world understand how cruel war is," she said. "If we can stop war, we should stop it."

Chen Deshou with family members Photo: Courtesy of Chen Rong

In recent years, as long as his health allowed, Chen Rong and other family members would accompany Chen Deshou, who is 93-year-old this year to public commemorative events. This year, however, things were different. He slept through much of the day. Chen Rong said she plans to speak with him the next time she visits, bringing along the yellowed notebook and the handwritten testimony he once prepared, page by page, in his own careful script.

At the end of that testimony, written in Japan in December 2014, Chen Deshou wrote "Now my family has eight members again. In this era of peace, I want to tell the public that we must not forget this tragic history. The younger generation should know that war brings only disaster to people. Only peace can bring a happy life. We want peace and friendship, not war."